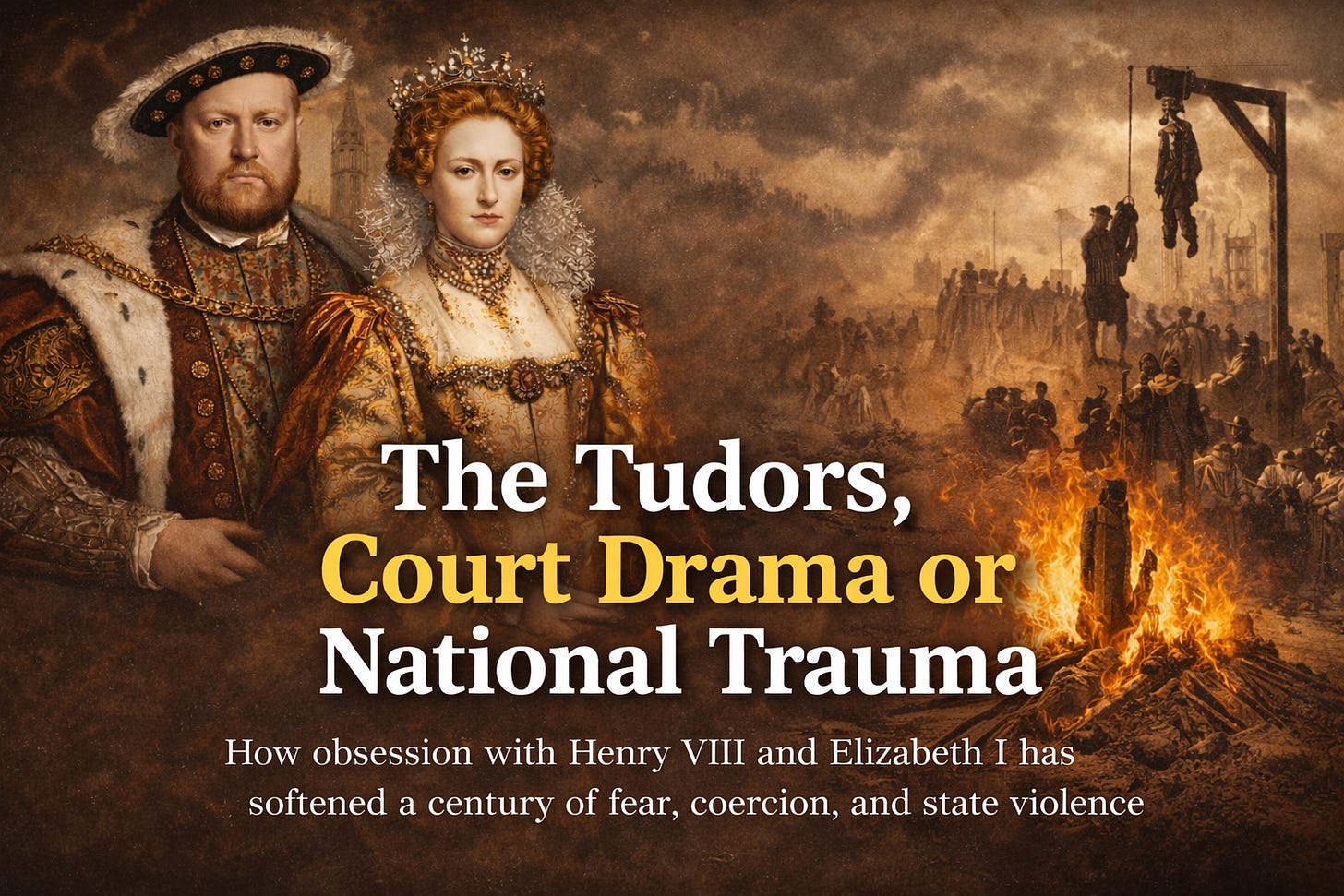

The Tudors, Court Drama or National Trauma

How obsession with Henry VIII and Elizabeth I has softened a century of fear, coercion, and state violence

There are few periods in English history as overexposed as the Tudor century. It dominates classrooms, documentaries, historical fiction, and the collective imagination. We know the silhouettes, the slogans, the portraits. Six wives. Bloody Mary. Gloriana. A nation stepping confidently into modernity.

Yet this familiarity has dulled something essential. The Tudor age has been repackaged as spectacle, as personality politics, as a gallery of temperaments and tantrums. What slips from view is the experience of living through it. For millions, this was not a golden age but a time of grinding uncertainty, religious terror, and profound social upheaval. The fixation on court drama has turned a national trauma into something oddly comforting.

This matters. Not because the Tudors are misunderstood, but because they are understood too narrowly.

Tudor obsession and historical comfort

The Tudors feel knowable. That is part of their power. They left faces behind, names, buildings, quotable moments. Henry VIII looms large, a monarch whose private life has been treated as public entertainment for five centuries. Elizabeth I endures as an icon of poise and permanence, endlessly invoked as proof that England once found steady leadership through force of character alone.

This focus on individuals has made the era digestible. We watch the Tudors as we would a family drama, complete with betrayals, rivalries, and sharp dialogue. Power becomes theatrical. Violence becomes episodic. Suffering is implied rather than confronted.

What this framing offers is reassurance. If history can be reduced to a handful of colourful figures, then chaos looks manageable. Structural fear becomes personal eccentricity. Systemic violence is softened into bad behaviour by extraordinary people.

But history lived from below rarely aligns with history remembered from above.

Religion as instrument of fear

For those outside the court, the defining feature of the Tudor century was not romance or rivalry. It was terror rooted in belief. Religion was not a private matter of conscience but a public test of loyalty, enforced with ruthless consistency and sudden reversals.

Within a single lifetime, English subjects were required to change their faith repeatedly. Catholic, Protestant, Catholic again, then Protestant once more. Each shift was presented as moral certainty. Each demanded visible compliance. To hesitate was dangerous. To dissent was fatal.

This was not an abstract theological debate. It shaped daily life. What prayers could be said. Which books were legal. How neighbours were judged. Families learned to keep their convictions quiet, or learned to perform belief as survival. Silence became a skill. Ambiguity a refuge.

Executions were not rare aberrations but part of the political language of the age. Burnings, beheadings, and public punishments served as reminders that faith and obedience were inseparable. The state demanded not only loyalty, but affirmation.

When modern culture celebrates the Tudor settlement as a necessary step toward modern Britain, it often overlooks the cost. Stability was achieved through coercion. Unity was enforced by fear. Religious violence was not incidental to Tudor rule, it was central to it.

Social rupture beyond the palace

Away from the court, the Tudor period was marked by dislocation. The rhythms of medieval life were disrupted with astonishing speed. Population growth strained resources. Prices rose. Wages stagnated. Traditional systems of charity and care were dismantled.

The dissolution of the monasteries is often discussed in terms of land redistribution and royal finance. Less attention is given to what vanished overnight. Monasteries were employers, landlords, hospitals, schools, and welfare providers. Their destruction removed a social safety net that had taken centuries to form.

Communities felt the loss immediately. Poverty became more visible. Vagrancy more criminalised. Laws grew harsher. Punishment replaced provision. The state increasingly treated hardship as moral failure rather than structural reality.

Enclosure transformed landscapes and lives. Common land disappeared behind hedges and legal deeds. Subsistence farming gave way to profit. Displaced labourers drifted toward towns ill-equipped to absorb them. Anxiety deepened. Resentment simmered.

Rebellion followed, not as isolated unrest but as repeated eruption. These were not romantic uprisings but desperate acts by people who felt the ground shifting beneath their feet. Order was restored through force, not negotiation.

The Tudor state learned how to govern through surveillance, law, and punishment. These tools would endure long after the dynasty itself had faded.

Violence as policy

It is tempting to describe Tudor brutality as the product of unstable personalities. This interpretation comforts us. It implies that cruelty was accidental, the result of temper rather than design.

The truth is more troubling. Violence was policy. Executions were calibrated displays of authority. Terror was not a failure of governance but one of its methods.

The law expanded dramatically, not to protect but to control. Treason was redefined and broadened. Words became dangerous. Silence could be interpreted as guilt. Loyalty was measured constantly, publicly, and harshly.

Women suffered particular vulnerability. Accusations travelled quickly. Reputation became a weapon. A whisper at court could end a life. Marriage to power offered proximity, not safety.

This was a society learning how to centralise authority, how to make the state present in every parish, every conscience. The Tudor legacy is not simply monarchy reshaped but governance hardened.

Yet popular memory often glosses this reality. We remember executions as plot points. We remember laws as background detail. We forget the atmosphere of fear that made obedience routine.

Why this blind spot endures

The Tudor century remains irresistible because it flatters national myth. It offers origins. It supplies familiar villains and heroic survivors. It allows England to imagine itself as forged through personality rather than pressure.

Later generations amplified this image. Victorians romanticised the period as vigorous and decisive. Empire needed ancestors. Protestant triumph needed narrative clarity. Complexity was inconvenient.

Modern media has continued the pattern. Court-centred storytelling sells. Intimate drama attracts audiences. Structural suffering does not.

There is also comfort in distance. The Tudors feel far enough away to enjoy safely. Their violence can be acknowledged without consequence. Their authoritarianism can be tutted at without reflection.

But this selective memory carries risk. When history becomes entertainment alone, it loses its warning function. The Tudor age reminds us how quickly fear can be normalised, how easily belief becomes a tool of power, how fragile social stability can be when authority governs through threat.

Remembering the century whole

This is not an argument to abandon Tudor history. It is an argument to see it whole.

Henry VIII and Elizabeth I mattered. Their decisions shaped institutions, borders, and beliefs that still echo today. But they were not the only actors, nor were their reigns experienced primarily as drama.

For most people, the Tudor century was endured rather than admired. It was navigated carefully, quietly, often anxiously. Survival required adaptability, restraint, and luck.

To remember only the court is to miss the country. To focus on personalities is to ignore structures. To celebrate endurance is to forget suffering.

History’s blind spots are rarely accidental. They tell us what we prefer not to see. The Tudors remain popular because they are familiar, because they flatter, because they entertain. But they also deserve to unsettle.

If this series is to mean anything, it must resist comfort. It must return uncertainty to the past, and in doing so, remind us that stability, tolerance, and pluralism were hard won, and easily lost.