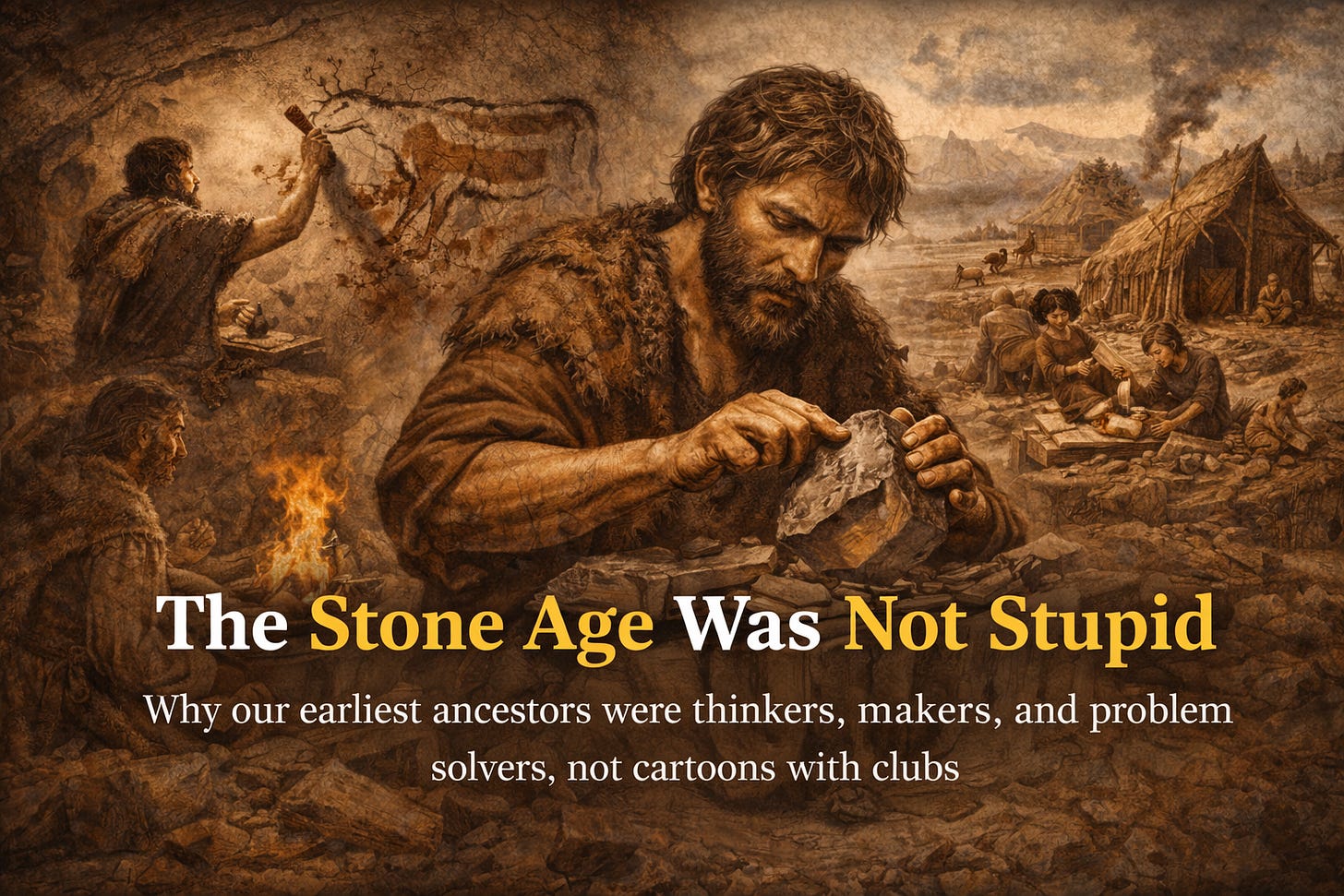

The Stone Age Was Not Stupid

Why our earliest ancestors were thinkers, makers, and problem solvers, not cartoons with clubs

If you want to insult someone in modern Britain, you do not reach for a complex historical critique. You call them Stone Age. It is shorthand for ignorance, brutality, and intellectual absence. The phrase lands easily because we have been trained, almost from childhood, to picture early humans as dim, backward creatures waiting patiently for history to begin.

It is the same logic that underpins jokes about cavemen and cartoons where the past is populated by people who look like us but behave like toddlers. Progress, in this telling, starts later. Real thinking arrives with cities, writing, and polite table manners. Everything before that is rehearsal.

This is one of history’s most stubborn blind spots, and one of its most revealing. The Stone Age was not stupid. It was inventive, experimental, adaptive, and often astonishingly subtle. The problem is not the past, it is the way we have chosen to narrate it.

Problem with caveman shorthand

The phrase Stone Age does a lot of quiet damage. It collapses hundreds of thousands of years of human experience into a single insulting adjective. It suggests stagnation rather than continuity, simplicity rather than skill. Most dangerously, it implies that intelligence is measured only by how closely a society resembles our own.

Early humans lived without smartphones, bureaucracy, or written contracts. They also survived ice ages, crossed continents, mastered fire, and built social networks complex enough to endure for millennia. These are not the achievements of dull minds.

When we dismiss the Stone Age, we are often flattering ourselves. We imagine that we would cope better, think faster, innovate more. In reality, most of us would struggle to last a week without modern infrastructure. Intelligence is always shaped by environment. Early humans were brilliant at solving the problems they actually faced, not the ones we now take for granted.

Ingenuity without instruction manuals

Stone tools are often presented as crude, the clue supposedly sitting in the name. In fact, they represent deep technical knowledge passed down through generations. Tool making required understanding fracture mechanics, material quality, angle, pressure, and purpose. A poorly struck flint was wasted effort. A well made one could mean survival.

This knowledge was not written down. It was taught, observed, corrected, and refined. That alone tells us something important about communication, memory, and social learning.

Even more striking is the evidence of long distance thinking. Materials found at archaeological sites often originated hundreds of miles away. This implies trade, travel, negotiation, and trust. These people were not isolated brutes. They were networked communities operating across landscapes.

When we picture early humans wandering aimlessly, we erase the planning involved in seasonal movement, hunting strategies, and resource management. You do not coordinate large hunts or migrate successfully without leadership, cooperation, and shared understanding.

Art before agriculture

One of the most uncomfortable facts for modern assumptions is that humans created art before they created farming. The famous cave paintings at sites like Chauvet Cave and Lascaux are not idle doodles. They are deliberate, technically sophisticated works placed carefully within specific environments.

These paintings use movement, perspective, and natural contours of rock. They were made in spaces that required effort to access. This was not casual decoration. It was meaningful expression, whether spiritual, social, or symbolic.

Art requires abstraction. It requires imagining something that is not physically present and bringing it into being. That alone dismantles the idea that early humans lacked imagination or complexity. You do not produce art if you cannot think beyond the immediate moment.

Homes, not holes

The popular image of people shivering in caves is misleading. Caves were used, yes, but often as seasonal shelters or ritual spaces. Many Stone Age communities built sophisticated homes using wood, bone, hides, and earth. The problem is not that these structures did not exist, it is that they rarely survive.

At sites like Skara Brae, stone preserved what was once common. Furniture, storage, and spatial planning show a concern for comfort, order, and daily routine. These were not people barely clinging to life. They were people organising it.

The idea that domestic life only begins with later civilisations is comforting, because it allows us to claim emotional depth as a modern invention. Archaeology tells a different story. Care for children, the elderly, and the injured appears far earlier than we once believed.

Social intelligence and care

One of the most revealing pieces of evidence from the Stone Age is survival itself. Skeletal remains show individuals who lived for years with injuries or conditions that would have made independent survival impossible. That means someone else helped them.

Care is a social choice. It requires empathy, obligation, and cooperation. It also suggests moral frameworks, even if they were not articulated in words we recognise.

Burial practices reinforce this picture. The deliberate placement of bodies, the use of grave goods, and repeated attention to the dead all point to emotional bonds and shared meaning. These people mourned. They remembered. They did not simply move on.

Why we prefer them simple

So why does the idea of a stupid Stone Age persist? Because it flatters modern confidence. If the past is foolish, the present feels inevitable. Progress becomes a straight line rather than a series of choices, accidents, and adaptations.

There is also a political comfort in imagining early humans as savage. It allows later violence to be framed as improvement. Civilisation, in this story, tames brutality. The truth is messier. Violence, creativity, cooperation, and cruelty appear throughout human history, in varying proportions.

Reducing the Stone Age to stupidity also creates distance. It reassures us that we are fundamentally different, more advanced, more rational. Yet many of our deepest instincts, fears, and social behaviours were shaped long before writing appeared.

Modern mirror we avoid

Here is the uncomfortable analogy. Calling the Stone Age stupid is like dismissing someone because they cannot code while ignoring the fact they can build a house, grow food, and fix an engine with their hands. Intelligence is contextual. It always has been.

Our ancestors did not lack brains. They lacked the same problems. They solved different ones, often with elegance. They built worlds that worked long enough for us to inherit them.

The Stone Age was not a prelude waiting for civilisation to arrive. It was civilisation, just operating under different rules.

Perhaps the real blind spot is not how little they knew, but how much we forget that thinking did not begin when history started writing itself down.