On This Day in 1979: The Assassination of Lord Mountbatten

Mountbatten’s assassination sent a brutal message: no one was off limits.

Mullaghmore, County Sligo. A beautiful place on any postcard. The kind of Irish coastal village where summer is still ruled by tide, net and boat. But on this day in 1979, it became the backdrop for a moment of calculated violence that shocked Britain and echoed across the world.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, a decorated war hero, a former Viceroy of India and a cousin of the Queen, was blown to pieces in a boat he took out most summers with family and friends. He died alongside his teenage grandson, a 15-year-old local crewman and his daughter’s mother-in-law. The bomb, planted by the Provisional IRA, was triggered remotely just moments after they left the harbour.

It was no accident, no warning shot. This was a surgical, symbolic, and ruthless act.

IRA Strategy Without Sympathy

To see this attack as random or personal is to miss the point. It was strategic, designed to draw attention to a cause that had already drowned in decades of bloodshed, but was now clawing its way into international headlines.

By killing Mountbatten, the IRA broke a barrier. They assassinated a royal. Not a soldier in a Belfast street, not a constable at a checkpoint, but a man from the highest echelon of Britain’s elite, on holiday, surrounded by children. There was no mistaking the intent. The message was clear: no one was untouchable, and the struggle over Northern Ireland would not respect borders, age or class.

The same day, 18 British soldiers were ambushed and killed in County Down. Together, these two events made 27 August 1979 one of the bloodiest and most politically loaded days of The Troubles.

Mountbatten’s Legacy Complicated by Partition

Mountbatten wasn’t just a victim. His legacy tied him directly to the deep colonial scars that the IRA and many Irish nationalists still felt. As Viceroy of India, he oversaw the rushed partition that split the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, triggering a humanitarian disaster and ethnic violence that killed over a million people. His reputation in Britain remained largely untarnished, even polished, but in post-colonial countries, the view was more nuanced.

The same applies to Ireland. Mountbatten had made Classiebawn Castle in Mullaghmore his summer retreat. He kept going there even as tensions rose and the risk of attack became real. Whether that was pride, arrogance or a refusal to concede ground to fear, it left him exposed.

Security was minimal. He declined military protection. For the IRA, that made him a sitting target.

War Tactics Dressed as Politics

By 1979, the Provisional IRA had mastered the art of asymmetrical warfare. Bombs, ambushes, targeted killings. Each act was calculated not only for military impact but also for political weight. Mountbatten’s assassination served both purposes: revenge for British oppression and publicity for the nationalist cause.

Yet this wasn’t just war. It was terror dressed as politics. The victims weren't combatants. A teenager helping with a boat. A holidaying grandmother. It made the act harder to justify and impossible to ignore.

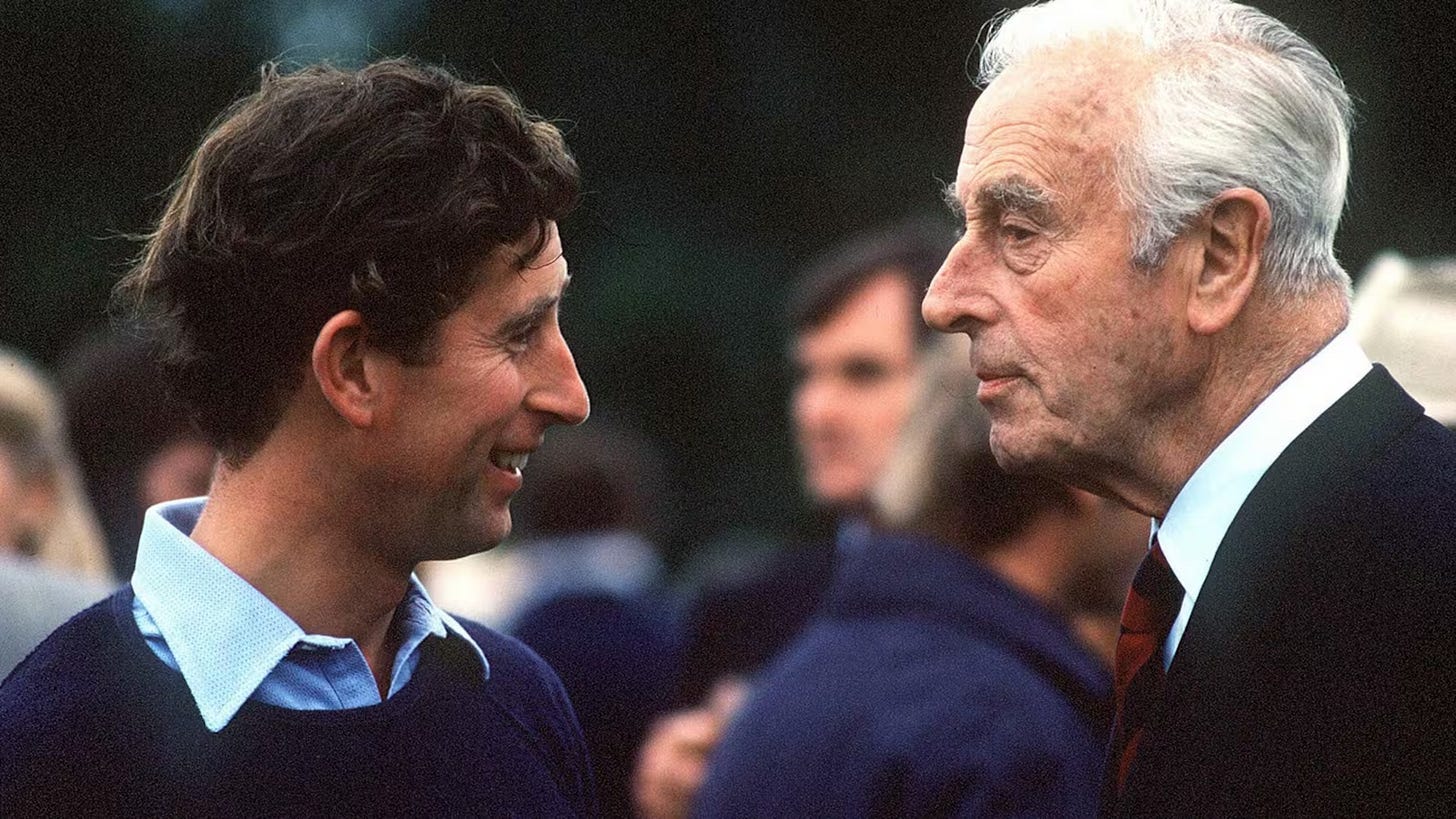

The backlash was swift. Britain grieved. Prince Charles, then in his early 30s, was visibly broken at the funeral. Mountbatten had been a mentor, perhaps the closest he’d ever had to a father figure. In Parliament, calls for tougher crackdowns followed. But so too did questions about how far this conflict could escalate.

From Murder to Handshake

Fast forward to 2012. In Belfast, Queen Elizabeth II extends her hand to Martin McGuinness, once a senior IRA figure believed to have had knowledge of Mountbatten’s killing. Cameras flashed, shutters clicked, and for a moment, the ghost of that summer morning in 1979 seemed to stand silently between them.

That handshake didn’t erase the past. But it acknowledged it. Northern Ireland’s road to peace had been brutal and uneven. The Good Friday Agreement, signed in 1998, had secured a kind of uneasy calm, built on compromise, forgiveness and an agreement to stop killing each other in the name of unity or division.

Thomas McMahon, the man who planted the bomb on Mountbatten’s boat, was eventually convicted but later released under the terms of the peace deal. Some called it justice delayed. Others saw it as a necessary part of the price for peace. Both were right.

Final Thought: Mullaghmore Still Holds the Silence

Walk along the Mullaghmore jetty today and you’ll see no plaques, no statues. Just sea, boats, rope and the slow rhythm of a fishing village that carries on. But the air still holds the weight of what happened.

Mountbatten’s killing changed the nature of the conflict. It forced Britain to confront the scale and intent of the Provisional IRA’s campaign, but it also exposed how far the legacy of empire reached, and how deep the wounds of partition still ran.

On this day in 1979, the war came not to a Belfast backstreet but to a quiet corner of the Republic. And in doing so, it proved that no war, no matter how rooted in history or ideology, can avoid staining the innocent.