On This Day in 1973, the Sydney Opera House Opened to the World

Fifty-two years later, this Australian icon still proves that great architecture is born not just from vision, but from endurance

On this day, 20 October 1973, Sydney finally unveiled the architectural marvel that had gripped its imagination for over a decade. With sails that seem to float on water and a design instantly recognisable across the globe, the Sydney Opera House stands as a monument to artistic ambition, civic struggle and lasting legacy.

I last visited the Opera House in 2009, during England’s victorious Ashes tour, a trip etched in my memory not just for the cricket but for the sight of that building rising out of Sydney Harbour like a hallucination rendered in concrete. Two days ago, I circled it again, though this time virtually, on my iFit treadmill. I could feel the pull of its geometry even through a screen, which says everything about how deeply this structure gets under the skin. It is magnificent in person, and remarkably magnetic even in pixels.

As a history writer, I believe the real story of the Opera House is not its opening ceremony or postcard image, but the struggle behind its creation and what that struggle reveals about Australia’s coming of age in the modern world.

Born from a sketch, built through conflict

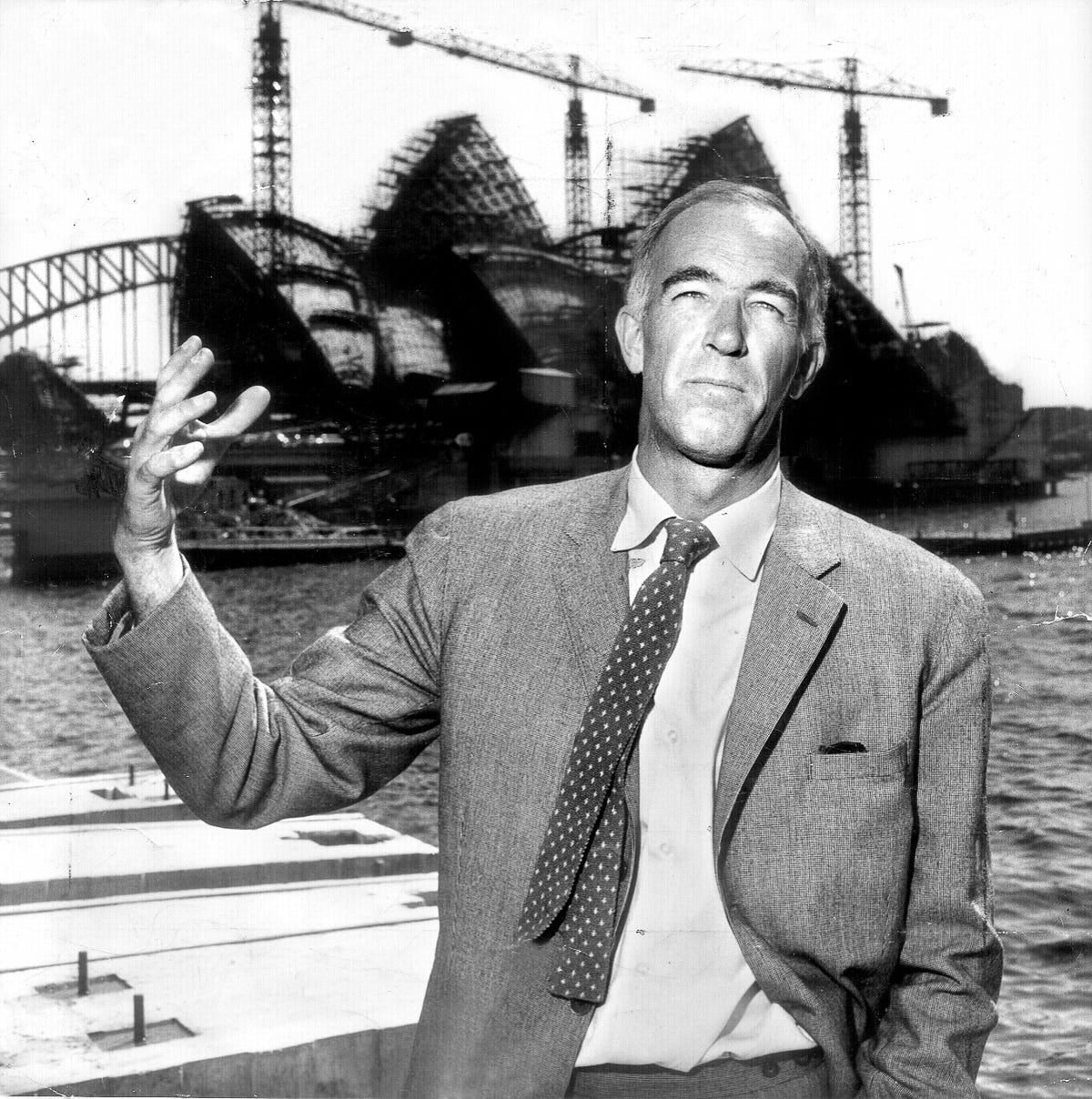

In 1957, a design competition was announced for a new performing arts venue at Bennelong Point, a finger of land curving into Sydney Harbour. The winning design, selected from over 230 entries, came from Danish architect, Jørn Utzon, whose vision was unlike anything else submitted. His concept was radical, not just in shape but in spirit. It imagined a building that could be viewed from every angle, function at massive scale, and still carry an elegance suited to its harbour setting.

That concept caught fire. But the real challenge was turning that drawing into something that could actually stand.

Construction officially began in 1959. From the very start, the project was fraught. Politicians were impatient, budgets exploded and the technical demands of building the curved roof shells outstripped both the technology and the funding available. After years of trial, failure and redesign, the architect and his engineering team eventually cracked the code. They realised the shells could be formed as segments from the same sphere. This breakthrough reduced complexity and cost, but not enough to appease the changing government.

By the mid 1960s, the political tide had turned. Utzon was pressured, then sidelined, then replaced entirely. He left the country in 1966, never to return, and was not even named during the opening ceremony in 1973. Not in speeches, not on the plaque. He was effectively erased from the ribbon-cutting, but never from the building.

More than a building, a national reckoning

The transcript I’ve drawn from makes one thing very clear. This wasn’t just an expensive building or a stalled project. It became a symbol of the push and pull between vision and control, between what a nation wants to be and what it can manage in the moment.

This is where my opinion lands. The Sydney Opera House matters not simply because it is beautiful, but because it represents the courage to build something bold, messy and essential. It captures a point in time when Australia, still shaking off the shadows of Empire, wanted to say something new about itself on the world stage. That it was willing to pour resources, energy and reputation into a shape so unfamiliar shows a maturity that has only become more clear with time.

Even the conflict is part of the story. Yes, it went wildly over budget. Yes, the timeline blew out by a full decade. And yes, the man who started it all was forced out before the first curtain ever rose. But none of that detracts from the outcome. In fact, it elevates it.

The Opera House was not born out of neat planning. It was pulled into being by sheer belief, adjusted on the fly, and saved by a public unwilling to settle for ordinary.

A view worth running for

When I laced up two days ago and set off on my treadmill, choosing a scenic Sydney route on iFit, it was the Opera House I looked forward to most. Even on a glowing display, even with distance and sweat in the way, there is something stirring about seeing it again. It’s a rare building that can dominate a skyline and still feel alive up close.

In person back in 2009, the feeling was electric. That was a trip for the cricket, yes, but the Opera House stayed with me longer than any scorecard. It has that effect.

In the flesh, the interplay of light and shadow across its tiled roof curves feels less like architecture and more like performance. That’s the irony. What was built to house opera, theatre and symphony has become its own stage, its own cultural act.

Still rising, still relevant

The Sydney Opera House remains one of the most visited and photographed landmarks in the world. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site, a working arts venue, and the centrepiece of modern Sydney. But more than any of that, it is a building that changed the expectations of a continent.

For Australia, it signalled a break from the past. It told the world that something original could rise from this corner of the globe. For architecture, it pushed the limits of what was possible before computers were widely used in design. For politics, it was a cautionary tale of short-termism and interference.

And for those of us who care about history, it is a case study in the power of holding firm to an idea, even when everything around you begs for compromise.

I believe that matters more than ever today. We live in a time of risk-aversion, tight budgets, safe choices. The Sydney Opera House reminds us that some of the most lasting triumphs come from the opposite mindset. The mindset that says yes, it might fail, but what if it doesn’t?

On this day, remember what was risked

So yes, remember 20 October 1973 as the date the Sydney Opera House opened to the public. But also remember the years before that date. The false starts. The forced resignations. The infighting and stubbornness. The quiet genius who walked away from it all.

Remember that it stood unfinished for so long, visible from every ferry, every bridge and every office window. And yet still, people believed. Still, it rose.

As I ran around its edges on my treadmill, I felt none of the old tension. Just admiration. Not for the building alone, but for what it took to get there. The Sydney Opera House is no longer just a piece of architecture. It is a legacy. And one well worth sweating for.