On This Day in 1963, the Vajont Dam Disaster Wasn't a Natural Tragedy, It Was Man-Made

A towering dam, a shifting mountain, and a series of ignored warnings led to one of the worst engineering disasters in European history

History does not forgive silence. On the night of October 9th, 1963, a 246-foot wave swept through the Piave Valley in northern Italy, drowning villages, flattening homes and killing nearly 2,000 people. It wasn’t an earthquake or a storm. The dam did not break, but it might as well have.

The Vajont Dam disaster was not a natural accident. It was designed with ambition, pushed forward by power, and protected by silence. The mountain moved and the earth gave way, but the real collapse had already happened. It began years earlier, with the decision to ignore the science.

Built to Impress, Destined to Fail

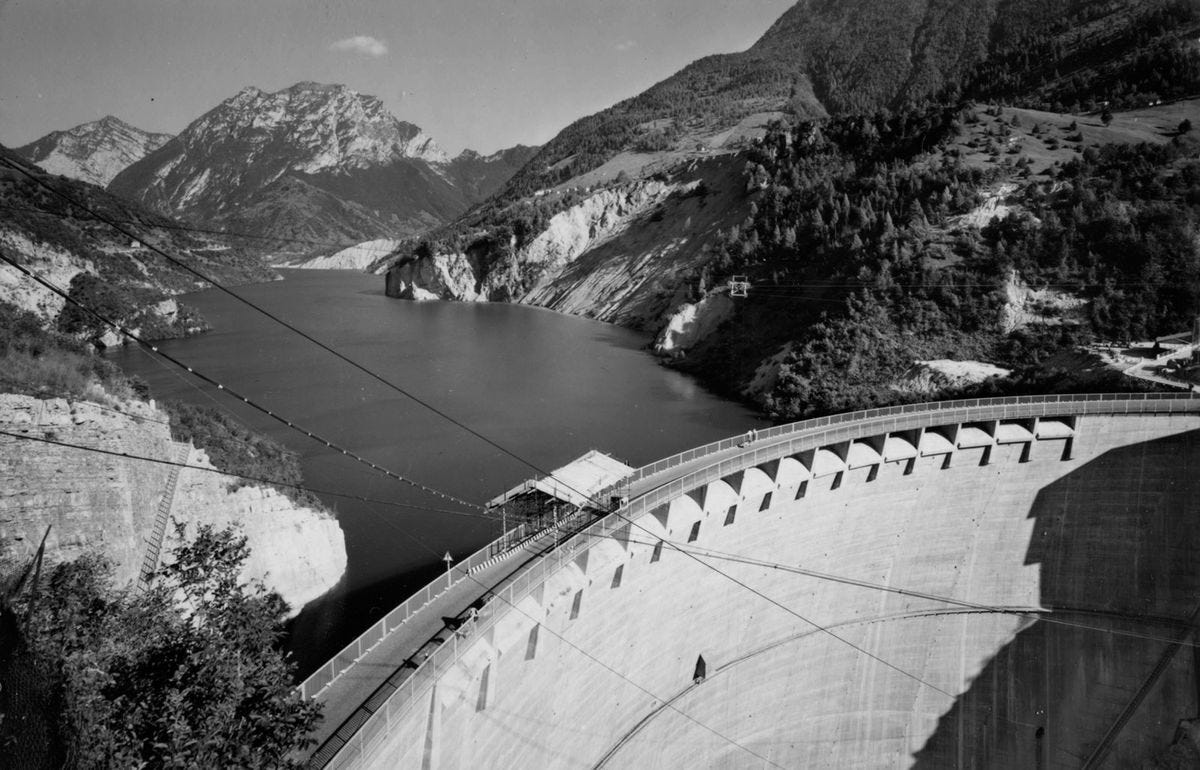

The Vajont Dam was meant to be a national achievement. At 860 feet, it was the tallest dam in the world at the time. It promised to power Italy’s postwar growth and become a monument to engineering strength. But it was built beside Monte Toc, known to locals as “the walking mountain” because of its long and visible history of landslides.

Warnings were raised early. In the 1950s, engineer Carlo Semenza, along with his son Eduardo, studied the region and identified an ancient landslide in the reservoir’s basin. It was clear that filling the dam could destabilise the slope. Their findings were documented with maps and photographs, and submitted to the Adriatic Electric Company, the powerful monopoly behind the project.

The company reviewed the warnings and chose to ignore them. The dam was too far along, too big to be questioned, and the politics too deeply entwined with its completion. Construction continued, and in 1960, as the reservoir was filled for the first time, a minor landslide triggered a wave over six feet high. It was a warning shot. Water levels were lowered temporarily, but no fundamental changes were made.

The Science Was Clear, the Silence Was Chosen

Throughout the early 1960s, signs of danger piled up. The mountain shifted. Earthquakes were recorded. Local residents reported strange movements in the land. But government officials, now responsible after the dam was nationalised, continued the same policy as the private company before them: dismiss the experts and silence the press.

Journalists who tried to report on the risks were met with legal threats. Engineers who raised concerns were sidelined. When Carlo Semenza died from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1961, his son Eduardo carried on the fight for safety, but his voice was drowned out in the noise of bureaucracy and industrial pride.

By 1963, water levels were again rising. Despite previous test results showing that a major landslide could generate a deadly wave, officials believed they had left enough margin by lowering the waterline to 82 feet below the top. They were wrong.

The Wave That Changed Everything

At 10:39 pm on October 9th, a mass of rock, earth and forest the size of a city broke off Monte Toc and crashed into the reservoir. The wave that followed was not a splash, it was a wall. It rose instantly, cleared the dam’s edge and thundered down the valley at terrifying speed.

Villages like Longarone were erased in seconds. Entire families vanished. Clothes were ripped from bodies by the pressure of air, and survivors were left in shock, surrounded by silence and mud. The dam itself remained standing, a brutal irony, as everything it was meant to protect was destroyed beneath it.

Rescue teams faced impossible conditions. Roads were gone. Communication was lost. When they finally reached the valley, they found devastation: houses turned to dust, streets washed away, and a death toll that would eventually rise above 1,900. Some estimates place it closer to 2,500.

What We Choose to Remember, and What We Refuse to Learn

In the days that followed, officials called it a freak event. A natural disaster. An act of God. But it wasn’t. It was a human-made catastrophe, driven by arrogance, denial and the refusal to listen.

The evidence had always been there. Engineers warned of the danger. Local people voiced their fears. The science was not new, just inconvenient. And when truth becomes inconvenient, history has shown us time and again what follows.

The Vajont Dam still stands today, no longer in use. It has become a grim tourist attraction, a place where visitors can walk across a structure that once symbolised progress but now carries the weight of mass death and misjudgement.

There was no justice for the dead. No public trial for those in charge. No real reckoning. The companies, the politicians, the managers, all moved on. The survivors rebuilt, but the valley would never be the same. A modern engineering marvel had been reduced to a cautionary tale.

This was not a story of nature’s fury. It was the result of wilful ignorance. The lesson is as clear today as it was in 1963. When warnings are ignored and voices are silenced, disaster becomes inevitable. Not by chance, but by choice.

And so, we remember this date. October 9th, 1963. Not just for the lives lost, but for what those lives can still teach us.