On This Day in 1958: The Day a Nobel Prize Broke a Russian Poet

How the Nobel Prize for Boris Pasternak became a battleground between poetry and power

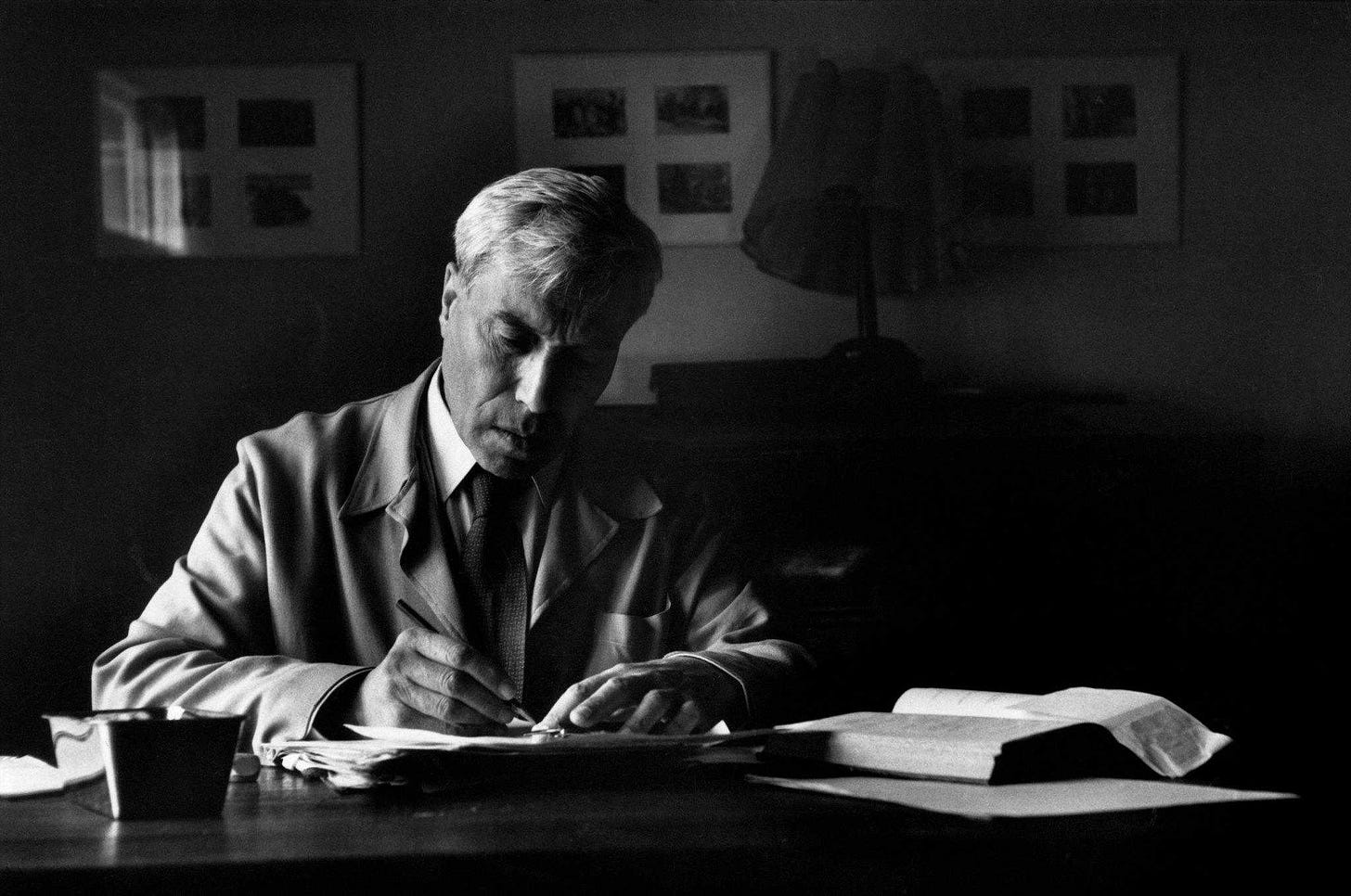

When the announcement broke on 23 October 1958 that Boris Pasternak had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition,” it seemed at first to seal his place in the pantheon of writers. Yet behind the public accolades lay a far darker story of coercion and moral compromise, one that in many ways defines the tortured relationship between a creative individual and the state that claims him.

From my vantage as a writer, standing in the shadow of the past and bringing old stories into the present, I find that the Pasternak case teaches us this: true literary recognition may arrive at the same moment as one’s enmeshment in political theatre. His prize was as much a cultural weapon as a personal honour, and the cost fell not only on himself but on those he loved.

Enduring art over fleeting acclaim

Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago, smuggled out of the Soviet Union and published in the west in 1957, was the spark for the Nobel. It confronted the Soviet state with its own shadows, weaving the landscapes of land and sky with the turbulence of revolution and love. The prize announcement on 23 October signalled that the world had taken notice.

Yet the triumph was hollow. The Soviet authorities had already banned his book, and the state-controlled narrative around Pasternak was quick to shift from acclaim to condemnation. The prize became a burden, not a badge of honour, because it brought state reprisals. He was humiliated by his fellow writers, expelled from the translators’ union, and warned he would never return if he travelled to accept the medal.

This tension between art and power resonates today. You may craft something that transcends your era, but your era may still deny you its peace. Pasternak refused exile and accepted his homeland’s embrace, but only under duress. The writing outlasted the regime.

Silent defiance in a whispering world

What strikes me most about Pasternak is his quiet defiance. He accepted the prize initially, his telegram to the Swedish Academy read “infinitely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed.” But within days, the weight of state pressure crushed that joy, and he was forced to renounce the prize, writing “Considering the meaning this award has been given in the society to which I belong, I must reject this undeserved prize.”

Here is the paradox. A man honoured for his originality and spirit became compelled to bow before the machinery of control. Yet his rejection was not surrender, it was a last act of survival. By remaining in Russia he protected what he could, his geography, his memory, his voice. The authorities may have silenced his public recognition, but they never silenced the work.

In our age of instant accolades and social-media commendations, Pasternak reminds us of the difference between recognition and freedom. He had one, but not the other. The writer’s soul remains intact when the prize is taken away, but the system that demands gratitude still exposes the cost.

Relevance for today’s writer and reader

For the modern reader and writer alike, Pasternak’s story holds practical lessons. First, value the work more than the awards. His novels and poems outlived the state that attempted to suppress them. Second, integrity may require restraint. In refusing to travel to Stockholm, he accepted a lesser visibility but kept his tether to place and identity. Third, history remembers honesty more than applause. In 1989 his son accepted the prize on his behalf, three decades too late, but the moral arc had shifted.

As someone who brings old stories into the modern era, I see in Pasternak the archetype of the artist under duress, who chooses the page over the platform, the poem over the podium. His place in history was assured not by the ceremony, but by the book that refused to die.

Legacy beyond borders

Though Pasternak died in 1960, less than two years after the prize announcement, his legacy endured. His funeral in Moscow saw thousands of mourners reciting his poems in a quiet act of rebellion. KGB agents prowled the crowd but could not stop the words. When the Soviet Union loosened its grip in the 1980s his novel was finally published on home soil.

On this day, 23 October 1958, we honour not only the moment of recognition but the meaninglessness of recognition when stripped of freedom. Pasternak reminds us that art grows in the soil of constraint and flourishes despite the wind of oppression.

In sum, the prize was bestowed, but the story remained his own. The regime could not dictate the book’s effect any more than it could command the wind to stop blowing through the pine canopy of Peredelkino. Pasternak’s voice remains, quietly, relentlessly alive.