On This Day in 1934: The Death of Pretty Boy Floyd

How a fugitive bank robber became a symbol of Depression-era resistance

A Cop Killer by Fact, a Folk Hero by Fiction

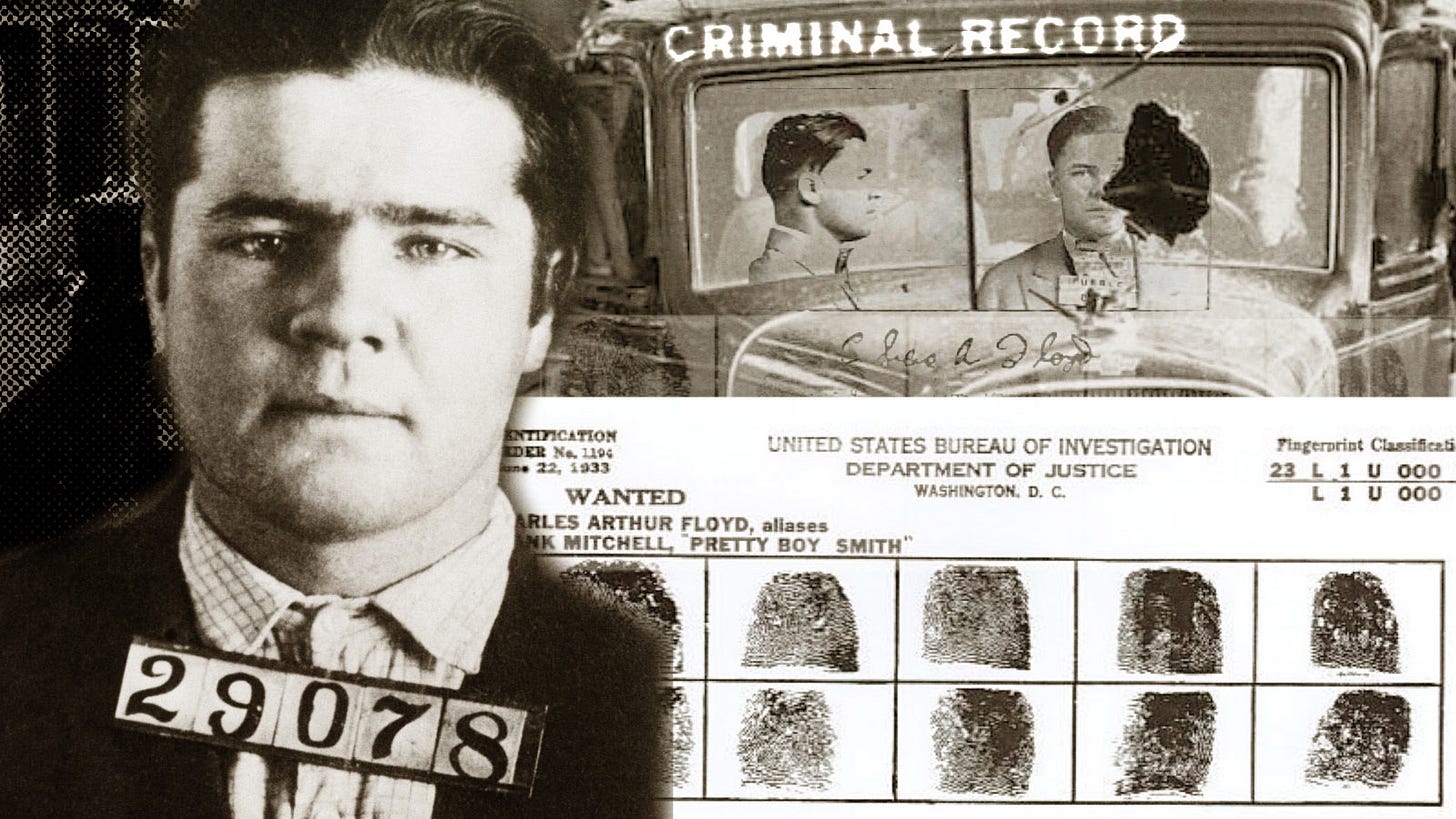

On this day in 1934, Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd was gunned down in a cornfield near East Liverpool, Ohio. He had spent nearly a decade living as a fugitive, robbing banks, dodging bullets, and building a reputation that blurred the line between criminal and legend. When agents from the Bureau of Investigation surrounded him and opened fire, they were not just closing a case, they were tying a bow on a story America had already turned into myth.

Floyd was no stranger to violence. He shot lawmen, evaded justice with blood-stained boots, and escaped prison with barely a scratch. But to many Americans of the 1930s, he symbolised something else entirely. To them, he was not just running from the law, he was running from a system that had failed.

What makes Floyd’s story fascinating is not whether he deserved the bullets that killed him. He almost certainly did. It is that so many people still argue whether he deserved a statue or a headline.

Life in the Shadows of a Failing System

Floyd was born in 1904 in Georgia, and his family moved to Oklahoma in search of a better life. Like many others, they found hardship instead. By the time he was in his teens, Floyd had already begun stealing. By 21, he was part of a botched grocery office robbery in St. Louis. That failed heist marked his first serious brush with infamy, and it came with a nickname that would follow him for life.

Witnesses described one of the robbers as a “pretty boy with apple cheeks.” It stuck, even though Floyd despised it. He wanted to be taken seriously. But the name stuck in headlines, and soon, it was being printed across America.

After serving time in prison for the robbery, Floyd walked straight back into the underworld. It was not a lapse in judgment. It was a decision. He saw more opportunity with a gun in his hand than behind a shovel.

As the Great Depression deepened, banks were foreclosing on homes, farmers were losing their land, and average people were growing bitter. Floyd became part of the narrative. Journalists told stories of him tearing up mortgage records during robberies, handing out stolen cash to the poor, and throwing coins to children as he fled. None of it was proven, but none of it needed to be. People wanted to believe it.

Floyd’s actual crimes were brutal and often fatal. He was linked to numerous killings, including law enforcement officers. Yet the image being shaped around him was not one of a killer. It was of a man punching up, not down.

The Kansas City Massacre and the Crosshairs of Hoover

By the early 1930s, Floyd had become more than a fugitive. He was a thorn in the side of the Bureau of Investigation, the federal agency that would soon be renamed the FBI. After the sensational Kansas City Massacre in 1933, where four officers and a prisoner were killed during a failed jailbreak, Hoover’s agents pinned the blame on Floyd.

The evidence was thin. Fingerprints found on beer bottles and speculative links to known associates were enough for Hoover to make Floyd public enemy number one. Floyd denied any involvement in the massacre, even sending a postcard to the Bureau to declare his innocence. But the Bureau had found its symbol.

Hoover was building something bigger than a case file. He was constructing an image of federal law enforcement that the public could trust. Floyd, with his romanticised newspaper stories and violent past, was the perfect antagonist. When Floyd was named as the prime suspect, the Bureau doubled its efforts, and Hoover used the moment to push for greater funding and power.

Floyd, meanwhile, kept moving. He fled with an accomplice and their girlfriends, crashed a car in the Ohio fog, then ran from the law one last time. When agents caught up to him on 22 October 1934, they opened fire, and he died soon after, insisting with his last breath that he had nothing to do with the Kansas City killings.

History Is Not Always Written by the Just

In the aftermath of his death, Floyd’s name lived on, but not in ways Hoover could fully control. Some newspapers wrote him off as a coward and killer. Others continued to tell stories about his so-called generosity and daring escapes. In Oklahoma, some townsfolk mourned him openly. Songs were written. His face appeared in pulp novels and ballads.

No one ever proved who fired the first shots in Kansas City. No one ever convicted Floyd for those killings. Yet Hoover’s Bureau used Floyd’s death as a turning point. It became part of the FBI’s founding legend, a symbol of federal strength and cross-state authority. Within a year, the Bureau would officially become the FBI, and its influence would grow into the powerful agency we know today.

Floyd, for his part, remains lodged in American memory somewhere between Jesse James and John Dillinger. Neither fully hero nor fully villain, he is a product of the era that made him. Desperate times crave icons, and when justice feels selective, even a bank robber can wear a halo in the right light.

What We Choose to Remember

The most enduring legacy of Pretty Boy Floyd is not the crime spree or the shootouts. It is the fact that he became something larger than his actions. He became an idea, bent to fit whatever story needed telling. To some, he stood for defiance in the face of economic ruin. To others, he was the face of lawlessness. To Hoover, he was a stepping stone. To history, he is still a question mark.

We mark his death on this day in 1934, not to glorify what he did, but to examine how stories are shaped, how enemies are chosen, and how myths are made. Pretty Boy Floyd lived a violent life. But the narrative that grew around him says more about the America of the 1930s than it does about the man himself.

That, perhaps, is the story worth telling.