On This Day in 1934: A Gunshot That Rewired a Nation

How the killing of Sergei Kirov opened the door to one of the darkest chapters in Soviet history

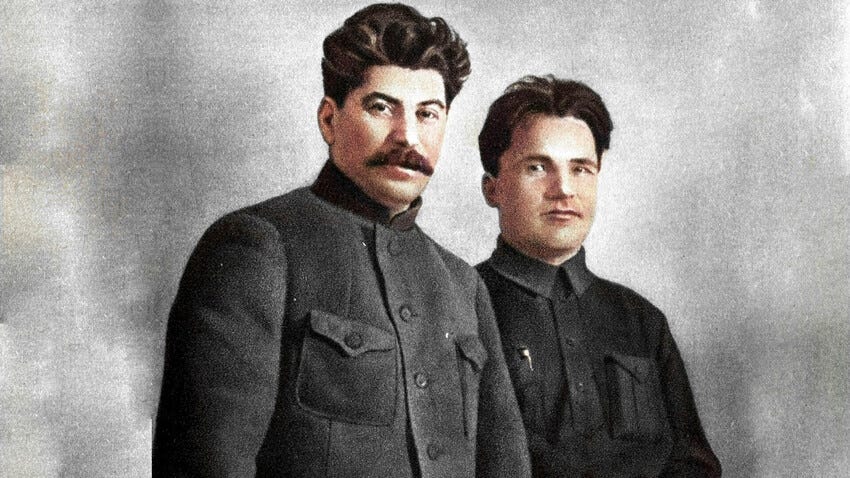

History rarely turns on a single moment, yet there are days when one event shatters the balance of power so completely that the aftershocks roll on for generations. On this day in 1934, the assassination of Sergei Kirov in Leningrad became one of those moments. It was a killing carried out by a troubled and resentful nobody, but its impact reshaped the Soviet Union in ways that still cast a long shadow.

As a writer who spends his days bringing old stories into the modern world, I am drawn to episodes like this. They remind us that political structures often appear solid until a single fracture exposes how fragile they really are. Kirov’s death did exactly that. It offered Joseph Stalin the perfect pretext to tighten his grip, silence rivals and unleash a terror that consumed the country he claimed to protect.

This is not a story about inevitability. It is a story about how power behaves when it fears losing control.

Kirov, the Party Favourite Who Had Become Inconvenient

Sergei Kirov stood apart inside the Soviet hierarchy. He was respected, charismatic and genuinely popular among party members, qualities that Stalin lacked and quietly resented. Even by the early 1930s whispers suggested that Kirov’s rising influence was beginning to trouble the man at the top.

This was the Soviet Union in an era already thick with rivalry. Lenin’s funeral a decade earlier is described as a gathering of solemn faces masking private ambition. Stalin, waiting for his chance, understood how dangerous a popular alternative could be. Kirov’s presence within the party was a reminder that leadership, despite appearances, was not entirely locked down.

Then came Leonid Nikolaev, a man whose life had unravelled under the weight of poverty, humiliation and his own obsessions. Fired from his job, stripped of his party membership and beset by jealousy, he convinced himself that Kirov was the source of all his misery. His decision to walk into the Smolny Institute and fire a single fatal shot was the act of someone seeking to reclaim a sense of power he had long since lost.

Yet Nikolaev’s personal collapse only explains the spark. The explosion that followed belonged to Stalin.

Stalin’s Seize of Opportunity

Stalin did not waste time. Nikolaev confessed to acting alone, but that was never going to serve the purpose the Soviet leader had already chosen. The transcript makes it clear that Stalin needed something concrete to justify ridding himself of rivals who had once stood against him. Kirov’s death provided the pretext.

Within weeks, the arrests began. Men who had previously challenged Stalin’s rise, even after meek apologies and years of quiet service, were dragged from their homes. Confessions were extracted through beatings and torture. Trials were held in rooms where the verdicts had been written long before the accused entered.

The execution of fourteen men less than a month after Kirov’s killing set the tone. More followed. Former political heavyweights who had shaped the revolution were paraded before tribunals to admit crimes they had not committed. Promises of leniency were dangled only to be withdrawn at the last moment. Nobody believed the outcomes were real, not even those who announced them, but the performance mattered. Terror works best when it is seen.

By 1936, the Moscow show trials had become central theatre in Stalin’s tightening chokehold on the Soviet Union. The old Bolsheviks, the men who had built the state, were destroyed under the glare of cameras and carefully crafted accusations. It was a purge carried out in the name of purity, but driven by paranoia and a hunger for absolute control.

What followed has been etched into the historical record as the Great Terror.

A Nation Frozen by Fear

Between 1936 and 1938, the machinery of repression operated without restraint. The arrests of military leaders, decorated soldiers, religious figures, intellectuals and even members of the NKVD itself. Nobody was exempt. Those who had pledged loyalty were swallowed up alongside those who had once voiced doubts.

The scale of the terror is still staggering. Hundreds of thousands were executed. Many more vanished into the Gulag with no hope of return. Families lived in dread of a knock at the door, all sense of justice replaced by a fear that did not break for decades.

All of it stemmed from a single killing on a winter afternoon in Leningrad.

The official Soviet line for years insisted that Kirov’s assassination was the work of a wider conspiracy. Only later, when silence finally cracked, did it become possible to question the truth. Historians still debate whether Stalin had any hand in the murder itself, but the evidence shows something important. Even if Nikolaev acted alone, Stalin understood the value of the moment and moved with ruthless efficiency.

For me, that is the real lesson. Power often reveals itself not in the plans set in motion, but in the choices made when opportunity arrives.

The Story We Still Need to Hear

Writing about Kirov’s death is not an exercise in recounting old horrors. It is a reminder of how fragile institutions can become when a leader believes dissent is a personal threat. It shows how quickly justice can buckle when fear is used as a tool. It proves that public popularity, the very trait that should have protected Kirov, can become its own kind of danger under the wrong kind of ruler.

On this day in 1934, one shot changed the Soviet Union. It strengthened a regime that would define the twentieth century and haunt its people for generations. History does not always give us a clean moral, but it gives us patterns. Kirov’s story shows the danger of leadership that fears competition more than failure, and the price a nation pays when power becomes an end in itself.

For a history writer, that is worth revisiting. It is worth retelling. And it remains a moment that speaks loudly to any age where authority grows nervous and truth is treated as something inconvenient.