On This Day in 1918: The Armistice Signed Too Late for 10,000 Men

How the final morning of World War I became one of its most senseless slaughters

War Was Won, But Men Still Died

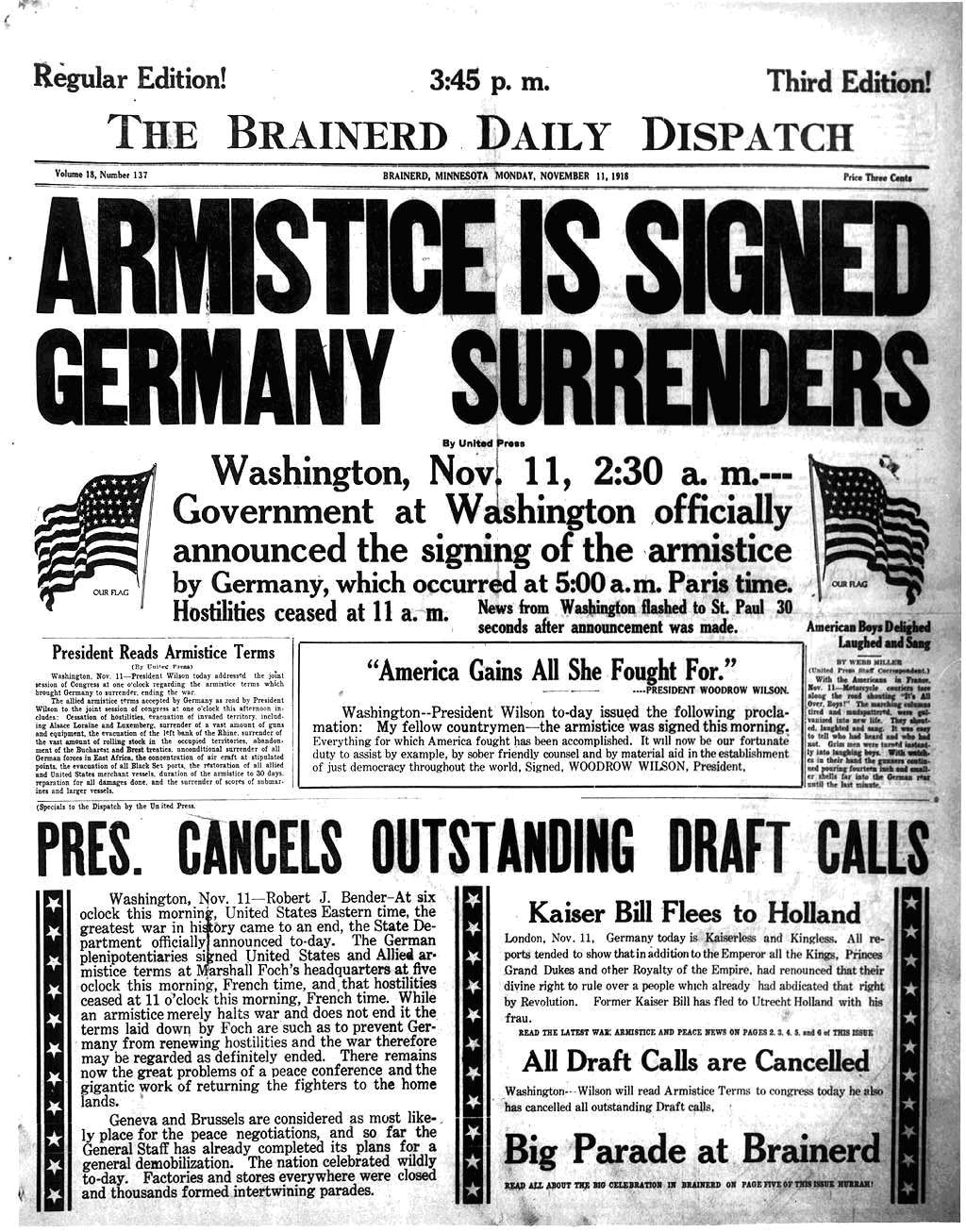

On 11 November 1918, the First World War officially ended. At 5:00 in the morning, in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiègne, the armistice was signed. Yet by 11:00, the time it was due to take effect, nearly 10,000 soldiers would be killed or wounded. This wasn’t the last gasp of a desperate conflict. It was known. It was avoidable. And it was unforgivable.

This blog is not a tale of heroism, but of cold decisions made far from the front lines. It is about how a war that had already ended on paper kept killing for six more hours. And why history should never forget the price paid in that silence between ink drying and guns falling still.

The Tragedy of Timing

By the autumn of 1918, Germany’s war machine had collapsed. The Allies were winning decisively. The Americans had added manpower and momentum, while the British and French regained key territory. Germany was isolated, starving, and broken in morale.

The signing of the armistice was less negotiation, more diktat. The Germans, led by Matthias Erzberger, came to the table stripped of leverage. Their only goal was to lessen the punishment. The terms offered were brutal: full withdrawal, disarmament, continued blockade and years of reparations. It was surrender dressed up in diplomacy.

But the real outrage is not what was signed. It is what followed.

Commanders on both sides were told when the ceasefire would come into effect. Eleven o’clock. Not before. And crucially, they weren’t given clear orders on what to do until then. Some held their positions. Others, disgracefully, launched final offensives—last-minute lunges at land or legacy.

They knew peace was coming. They still sent men to die.

Death With a Clock Ticking

Private Henry Gunther was 23 when he became the last American to die in World War I. He was shot at 10:44am, just 16 minutes before the armistice. The Germans even tried to wave him off, shouting warnings. He charged anyway, perhaps unaware the war was moments from being over. Perhaps not.

He wasn’t the only one.

In another corner of the front, French soldier Augustin Trébuchon was struck down at 10:55am. He had fought since 1914, survived Verdun and the Somme, and was killed five minutes before the silence. France later lied on his memorial, saying he died on 10 November. Even in death, he was politically inconvenient.

American General Charles Summerall, despite knowing the armistice was signed, ordered his troops to attack across a river. Over 1,000 men died in a few hours for no strategic value. Other Allied officers did the same, hoping to grab extra ground before the ceasefire froze the map.

Some commanders wanted revenge. Others wanted medals. All of them ignored the message that should have meant mercy.

Armistice as Political Performance

The armistice was less a peace agreement and more a declaration of domination. Marshal Ferdinand Foch, leading the Allied delegation, refused to shake Erzberger’s hand after the signing. This was not closure. It was spectacle.

Germany, though utterly beaten, was never invaded. This fed poisonous myths back home, that they were betrayed not defeated. These lies became the rallying cry of fascists, who painted men like Erzberger as traitors. He would later be assassinated by right-wing extremists in the Black Forest. His crime? Signing the armistice that stopped the bloodshed.

Foch himself knew the truth. After the Treaty of Versailles was signed the following year, he reportedly said, “This is not a peace treaty. This is war postponed for twenty years.” He was wrong only in that it took 21. The Second World War was born in the humiliation of the first.

What History Must Remember

When we mark Armistice Day, we rightly honour the millions who died between 1914 and 1918. But we should also ask why thousands had to die on the final morning. Why decisions made in safety condemned men who were already within reach of survival.

To say it was war’s nature is lazy. The orders were made by individuals. Generals chose ambition over restraint. Politicians chose punishment over peace. Those final hours reveal the heartless machinery behind the romanticised myths of war.

Soldiers like Gunther and Trébuchon were not symbols. They were real people who were knowingly sent to die in a war that had already ended on paper.

So, on this day in 1918, the war did not end with honour or unity. It ended with one final betrayal.