On This Day in 1911: The Mona Lisa Vanished and a Legend Was Born

How Vincenzo Peruggia’s Theft Turned an Overlooked Painting into a Global Icon

Theft Born of Patriotism and Poverty

On this day in 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre Museum in Paris. It wasn’t stolen by a criminal syndicate or an eccentric billionaire collector, but by a humble Italian handyman named Vincenzo Peruggia. A man overlooked by society and underpaid by his employers, Peruggia became the unlikely architect of one of the most significant moments in modern art history.

At a glance, the theft appears amateurish. Dressed in the white smock of museum staff, Peruggia simply walked into the Louvre on a Monday morning, the day the museum was closed to the public, removed the painting from its frame, tucked it under his coat, and walked out. The door was locked, so he unscrewed the knob. When a plumber stumbled across him, the worker helped him open the door without question. No alarms were triggered. No guards intervened. The painting simply vanished.

But to cast Peruggia as a fool who lucked into success would be to miss the deeper truth. His actions, as laid bare in his later trial, were not the mark of a thief chasing riches, but of a man driven by nationalism, grievance, and a desire to be recognised by the country that had so often shunned him.

Misunderstood Masterpiece

Prior to its theft, the Mona Lisa was admired by art historians and connoisseurs, but it did not command the awe and reverence it does today. In fact, when Peruggia plotted its return to Italy, he believed he was repatriating a stolen treasure, a victim of Napoleonic looting, wrongfully claimed by France. In truth, the painting had been legally acquired centuries earlier by King Francis I. But this misunderstanding did not stem from ignorance alone. It was rooted in a broader cultural grievance, the belief that Italy's artistic soul had been plundered, commercialised, and reframed by foreign powers.

Peruggia, once employed by the Louvre, had helped install the very glass case that protected the painting. He knew its vulnerabilities. He knew its value, not in francs or lire, but in symbolism. For him, the Mona Lisa wasn’t just a portrait of a Florentine woman by Leonardo da Vinci. It was a piece of Italian identity, misappropriated and misrepresented.

And so, he took it. Not to sell to the highest bidder, but to offer to a Florence art dealer for what he considered a fair ransom, enough money to lift him from his life of obscurity, and enough pride to restore his dignity.

The Trial That Shaped Public Perception

Two years later, Peruggia was caught when he tried to return the painting to Italy via a gallery in Florence. During his trial, he explained his motivations openly. He felt slighted by the French, mocked for his Italian heritage, and inspired by patriotic duty. His defence was not built on denial but on purpose. The court, and the Italian public, listened with interest. While his actions were criminal, they were not devoid of honour, or at least, not without the guise of it.

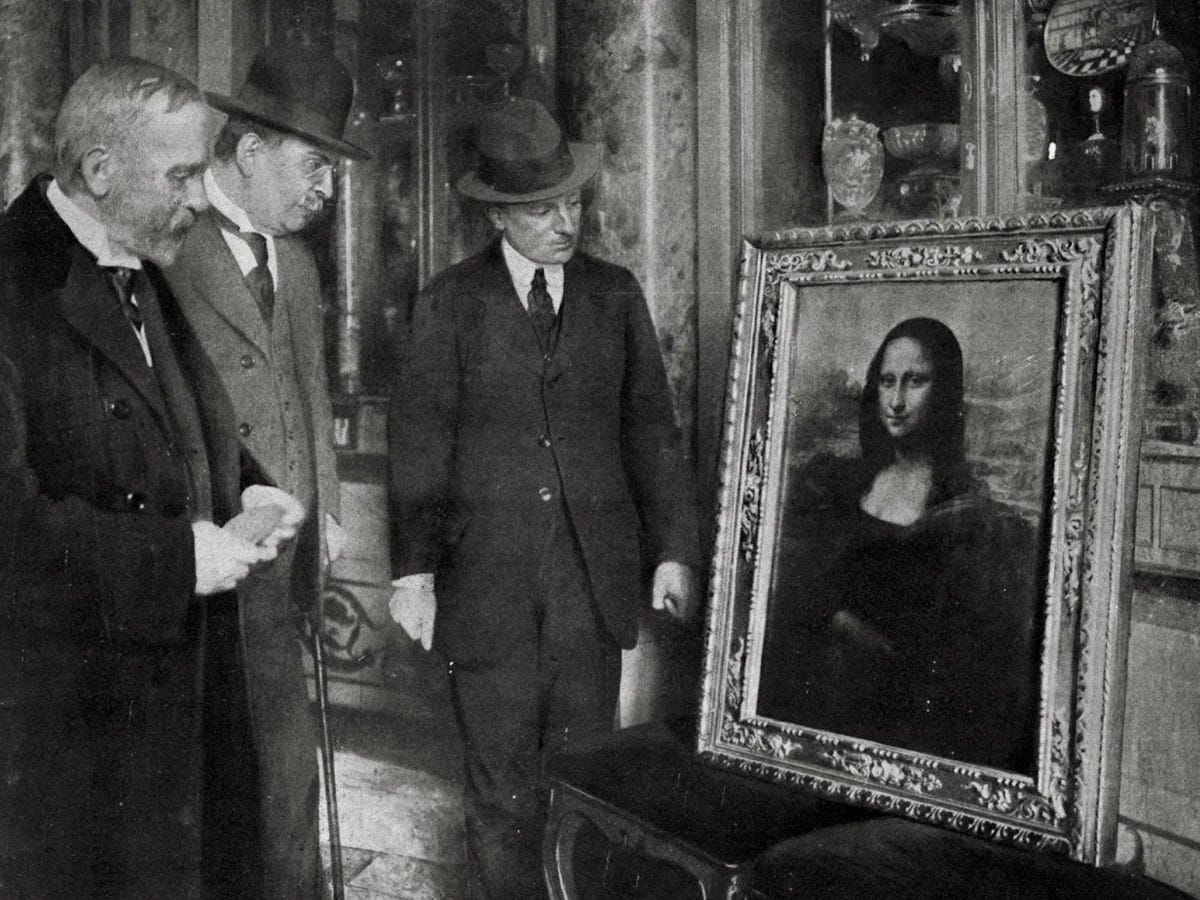

The judge explained that the Mona Lisa had not been stolen from Italy, as Peruggia had believed. The revelation shook him. Years of secrecy, risk, and misplaced pride seemed to unravel in a moment. Yet the jury showed sympathy. Perhaps because he was Italian. Perhaps because he brought the painting back in pristine condition. Perhaps because the world had changed since the theft, and the painting, once relatively obscure, had become the most talked-about artwork on the planet.

He was sentenced to just over a year in prison. He served seven months.

The Power of Absence

If Peruggia thought the theft would return glory to Italy, he was only partly right. The Mona Lisa did return to France, its place of residence restored. But its fame exploded. Ironically, by taking the painting off the wall, Peruggia placed it on the global stage. The empty frame drew more visitors than the portrait itself ever had. People queued to see the void, to feel the absence, to connect with something that was missing.

News of the theft spread around the world. Headlines ran daily updates. Suspects were named, including prominent artists who had nothing to do with the crime. The scandal gave the Mona Lisa something no artist, critic or monarch had previously given it, myth.

And myths are powerful currency in the art world.

After its recovery in 1913, crowds swelled to catch a glimpse of it. And over time, the painting became more than a Renaissance masterpiece. It became a symbol, of mystery, of fame, of value beyond reason. Today, it is estimated that 80% of Louvre visitors come just to see the Mona Lisa. Not because it is the greatest painting ever made, but because of the story that surrounds it. A story that truly began on this day, in 1911, when a short Italian handyman stepped into the Louvre with a plan and a white smock.

Legacy of a Man and a Painting

Vincenzo Peruggia’s story is one of irony and unintended legacy. He did not become rich. He did not receive accolades. He did not change the political landscape between France and Italy. But he did something remarkable. He transformed a painting from celebrated to iconic. He proved that context can elevate art more than technique. That mystery can fuel fame more than mastery.

In many ways, the Mona Lisa became modern because of Peruggia. Before him, it was a painting. After him, it was a phenomenon.

As a writer, I see moments like these, moments driven not by monarchs or ministers, but by ordinary people, as the true turning points of our past. Peruggia was not a genius, nor a saint. But he was a man who acted on conviction, however flawed. And in doing so, he shaped how the world sees art, fame, and even theft.

Today, over a century later, the Mona Lisa remains behind reinforced glass, protected by the latest security systems, under the watchful eye of millions. But it was once wrapped in a white smock, hidden under a hotel bed, and carried through the streets of Paris by a man whose name history almost forgot.

Almost.