On This Day in 1898: Soapy Smith Is Shot Dead in Skagway, Alaska

The Rise and Fall of a Con Man in the Age of Opportunity

Life Begins with a Shell Game

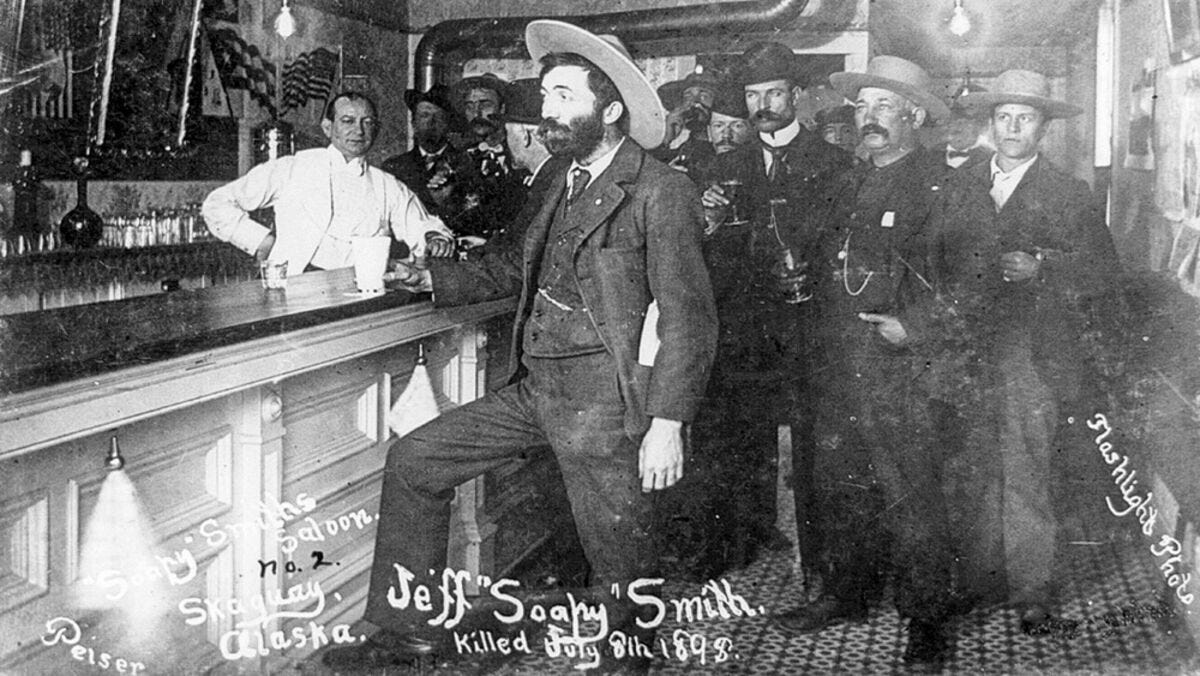

On this day, 8 July 1898, Jefferson Randolph Smith II met his violent end in the town of Skagway, Alaska. Known across the American frontier as Soapy Smith, he was not merely a criminal but a character so vividly drawn in the annals of the Wild West that his story continues to compel over a century later.

What began in the dust and chaos of San Antonio’s carnivals in the late 1870s became a life utterly devoted to deception. The young Smith, a cowhand flush with a month’s wages, lost everything to a slick-talking showman hustling a shell game. That moment, captured vividly in the accounts of his early days, did not crush his spirit. Rather, it galvanised his ambition. Smith did not walk away from the table with bitterness. He walked away with a plan.

There was a lesson in the illusion. A man could earn more in one afternoon spinning lies than he could breaking his back for weeks on the trail. In that moment, a conman was born, and history had its Soapy.

Soap Bars and Stagecraft

By the early 1880s, Smith had surfaced in Denver, where he perfected the grift that would earn him his moniker. The “soap scam” involved bars of soap supposedly wrapped with bills as high as one hundred dollars. With well-rehearsed panache, Soapy would sell the bars to onlookers, ensuring one of his own men, planted in the crowd, always found the prize first. The frenzy would follow. The crowd, full of hope and greed, would buy up the rest of the soap, but the money was long gone. The deception was precise. The stage was his, and the script belonged to him alone.

This was theatre, not just theft. Smith’s performances in the public squares of Denver became legendary. His voice was the hook, his charisma the bait. Yet while most conmen fled from the spotlight, Soapy sought it. He built an empire not in shadows but in plain view, drawing in citizens, politicians and lawmen alike.

He acquired buildings, including a fake ticket office near the train station, where travellers were lured into rigged games while they waited in vain for tickets that never existed. His criminal enterprise was vast and intricate, involving fraudulent lotteries, fake auctions, rigged poker games and worthless stock sales. All flourished under the protection of greased palms and smiling officials.

Empire Cracks in the Gold Rush

In 1897, when gold fever gripped Alaska, Soapy sensed fresh opportunity. He arrived in Skagway and found a town ripe for his talents. It was a place teetering on the edge of order, a transient settlement of hopeful miners and desperate chancers. Soapy moved quickly, establishing saloons, auction houses and stores. Most were legitimate in appearance only. Behind the façades, his criminal network fleeced newcomers with the same precision honed in Denver.

He controlled not just crime but, for a time, the town itself. His gang’s reach was so extensive that complaints went nowhere. Local authorities were either bought, bullied or bewildered into inaction. Soapy posed as a civic leader, even forming a “law and order committee” to fend off public scrutiny. His genius, if it can be called that, lay in orchestrating the illusion of authority while siphoning wealth from under it.

Yet power drawn from fear and fraud has a short half-life. As the con grew, so too did the resentment. Soapy had overplayed his hand.

Death at the Dock

On 8 July 1898, the final curtain fell. After his gang brazenly robbed a prospector of over $2,600 in gold, tensions in Skagway erupted. A citizens’ group known as the “Committee of 101” demanded justice and retribution. They called a public meeting to address the town’s lawlessness. Soapy, armed with his rifle and swagger, attempted to interrupt.

He found his path blocked by Frank Reid, a local engineer who stood guard. Words became threats, threats became bullets. In the end, Reid was mortally wounded, and Soapy lay dead with a shot through his heart.

It was not the law that stopped Soapy Smith. It was the town he thought he owned.

One Man, Many Masks

Soapy Smith’s story is a fable stitched into the fabric of American mythology, but not for the reasons popularised in western folklore. His tale is not one of outlaws versus lawmen, nor simply a rise-and-fall of a criminal. It is, at its core, a study in performance, identity and the seductive appeal of dishonesty cloaked in charm.

He understood something vital about people, particularly in times of flux. The frontier was a place of shifting truths. Gold rush towns and rail depots weren’t just economic centres, they were stages filled with wanderers seeking transformation. Soapy gave them a show. He played both the villain and the master of ceremonies. His schemes relied on complicity, the desire of the audience to believe they too might beat the game.

That is why he remains a figure of intrigue. He was not hiding in back alleys. He was selling illusions in the open, to anyone eager enough to suspend disbelief.

And when it finally collapsed, it did so as dramatically as he had lived. A fatal gunfight, a crowd in revolt and a legacy written in whispers and headlines.

In remembering Soapy Smith on this day, we are reminded not only of how far a grifter can rise, but how much of his success depended on a willing crowd. He made a fortune selling false hopes wrapped in soap paper, but his greatest trick was convincing the world he belonged in power.