On This Day in 1895: A Blast That Echoed Into Peace

How Alfred Nobel’s lifelong struggle with dynamite, duty and doubt reshaped the meaning of legacy

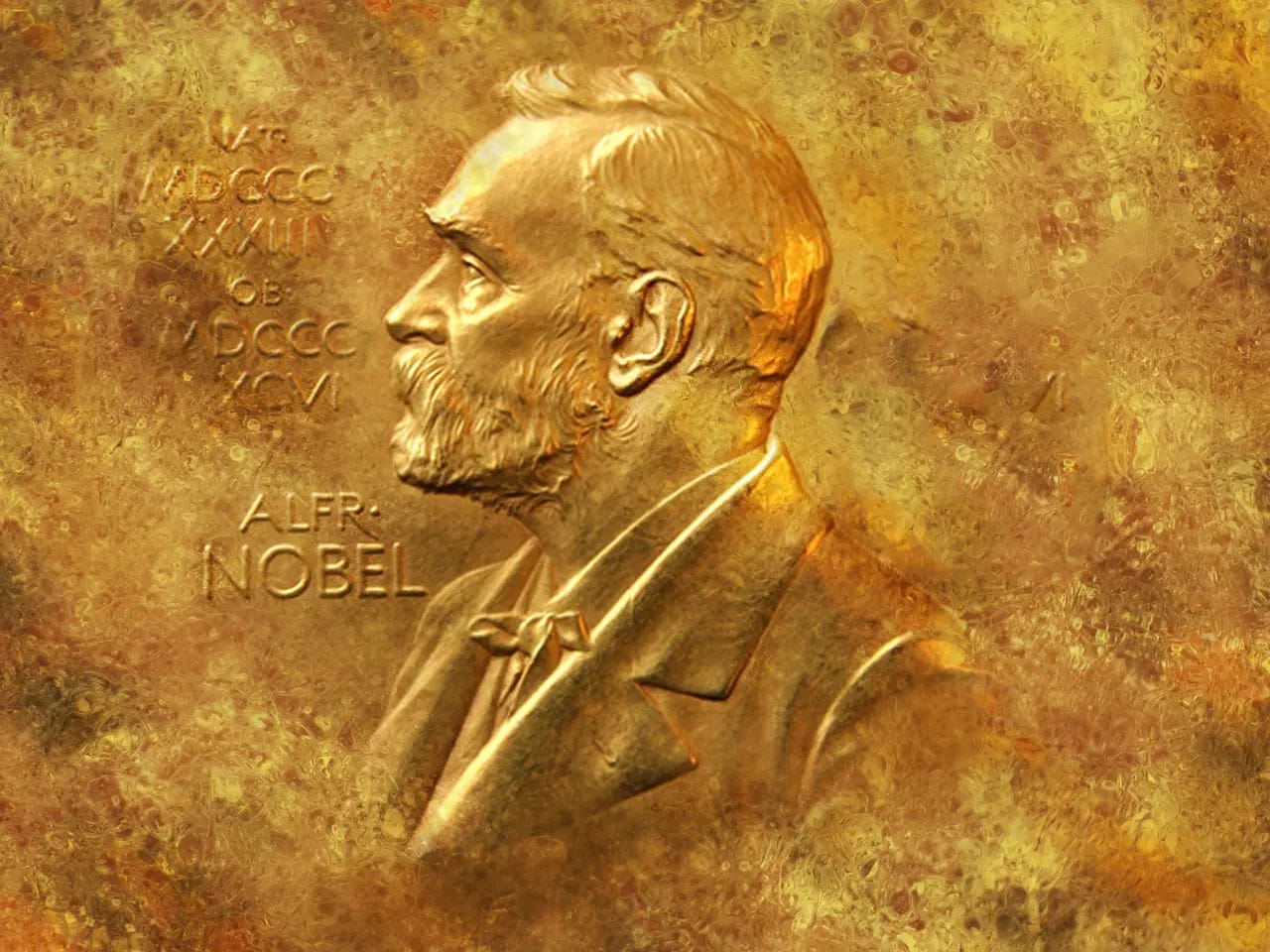

Every era throws up figures who seem carved from contradiction, men and women whose work brings progress and peril in the same breath. On this day in 1895, Alfred Nobel set his name to a will that tried to reconcile a life spent chasing the power of controlled destruction with a late awakening to the value of human betterment. As a history writer, I see his story as proof that legacy is rarely about the noise we make in life, but the quiet decisions we leave behind.

Alfred Nobel understood the weight of consequences long before he understood fame. His journey toward the Nobel Prize idea starts not with triumph, but with the shudder of an explosion and the stillness of loss. And that is what gives the origin of the Prize its moral force. Nobel did not create his celebrated awards from a platform of clean achievement. He created them from grief, guilt, ambition and a yearning to push humanity toward something finer.

This particular date in November matters because it marks the moment Nobel gave structure to a responsibility he had carried for years. It marks the moment he chose to balance the ledger.

Explosive ambition and its price

Nobel’s fascination with nitroglycerin was rooted in practical need and personal drive. His family’s chemical business offered him the materials, but it was his own restless mind that kept him chasing stability in a substance known for killing the men who touched it. That drive produced dynamite, the product that made his fortune and his reputation.

Yet what fascinates me most is not the invention, but the shadow it cast across him. Nobel saw first-hand the cost of volatility. He lost his brother in an explosion that tore through their Stockholm plant, a moment that might have ended his experiments. Instead, it hardened his resolve and pushed him across Europe searching for safer sites and safer formulas.

There is something striking in the image of him wandering the countryside near his German factory, rubbing algae rich sand between his fingers and deciding to test it with nitroglycerin. That instinct changed industry forever. Builders, miners and engineers adopted dynamite at astonishing speed because it allowed them to carve through landscapes that had resisted human effort for centuries.

But progress came with a body count. Workers mishandled it, armies exploited it, and Nobel watched his life’s work become a tool for deeper harm. It was not a surprise that he slipped into periods of gloom. He had unleashed something whose consequences he could not control.

This is the turning point where his story becomes more than a tale of invention. It becomes a question of moral weight.

Friendship, challenge and the reshaping of conscience

History often pivots on chance meetings, and Nobel’s bond with Bertha Kinsky was that kind of hinge. She entered his life through a job advertisement, and she changed his thinking by refusing to be impressed by his fame or his fortune. She understood him, but she did not indulge him.

Their conversations on peace and power, often sharp and probing, forced him to look at his own assumptions. Nobel believed that sheer destructive potential might scare nations into negotiation. Berta countered that peace demanded disarmament, not bigger blasts. Nobel respected her because she spoke without fear and because she cared enough to challenge him.

Though their brief romance faltered, their friendship endured, and it shaped Nobel’s final decade. Her novel, Lay Down Your Arms, pressed on him a truth he had resisted. It showed him that violence was not a lever that governments pulled for reason, but a reflex fed by fear, pride and rivalry. Nobel had always seen himself as a man of industry, not ideology, yet Bertha’s arguments landed where his own doubts had already begun to settle.

When he finally drafted his will on this day in 1895, it was her voice, as much as his own conscience, that guided his pen toward the idea of a peace prize.

This is what fascinates me about Nobel’s legacy. It was not born from clarity. It was born from tension, loss, affection and the hard realisation that progress means nothing if it does not protect lives as well as transform them.

Legacy shaped by a final decision

Nobel never had a family of his own, which may have freed him to imagine a different kind of inheritance. He had accumulated a fortune through his industrial success, yet he was fully aware that the world associated his name with devastation. The so called merchant of death headline that circulated during his life wounded him deeply, and while it did not define his motives entirely, it fuelled his wish to redirect his reputation.

His will was not a poetic gesture. It was a practical blueprint. He directed his wealth into prizes that would reward people who pushed humanity forward in science, literature and peace. He trusted that great minds, given resources and recognition, could tilt the world toward a better future.

His family contested the will, a reminder that even the boldest acts of conscience face earthly obstacles. But the idea held firm, and five years after his death, the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. They went on to honour figures who changed the landscape of knowledge and justice. Thinkers like Curie, Einstein and Martin Luther King Jr, people whose work stitched progress into the fabric of the century.

Yet I keep returning to the first Peace Prize winner linked to Nobel’s own story. Bertha von Suttner, his friend and fiercest intellectual sparring partner, received that honour. It was a full circle moment, proof that legacy can be shaped by the people we allow to challenge us.

What we learn on this day

Alfred Nobel’s story reminds me that legacy is not fixed by our greatest invention. It is fixed by our final intention. He spent his life mastering the chemistry of controlled destruction, yet his greatest act was one of controlled hope.

The Nobel Prize has taken on a life far larger than his factories or formulas. It signals human potential, human accountability, and the belief that knowledge should lift us, not endanger us. It is the product of a man who understood the price of explosive power and chose, late in life, to invest in the opposite.

On this day in 1895, Alfred Nobel wrote a will that still shapes the world. He understood that guilt is not enough. Reflection is not enough. Only action can tilt the scales.

That is why this date matters. It marks the moment he decided that the pursuit of invention must be matched by the pursuit of humanity. And that message, more than any scientific breakthrough, is the lesson worth carrying forward.