On This Day in 1877: How Wimbledon Began with a Broken Pony Roller and an Unlikely Dream

Wimbledon Tennis - From Humble Beginnings to Global Stage

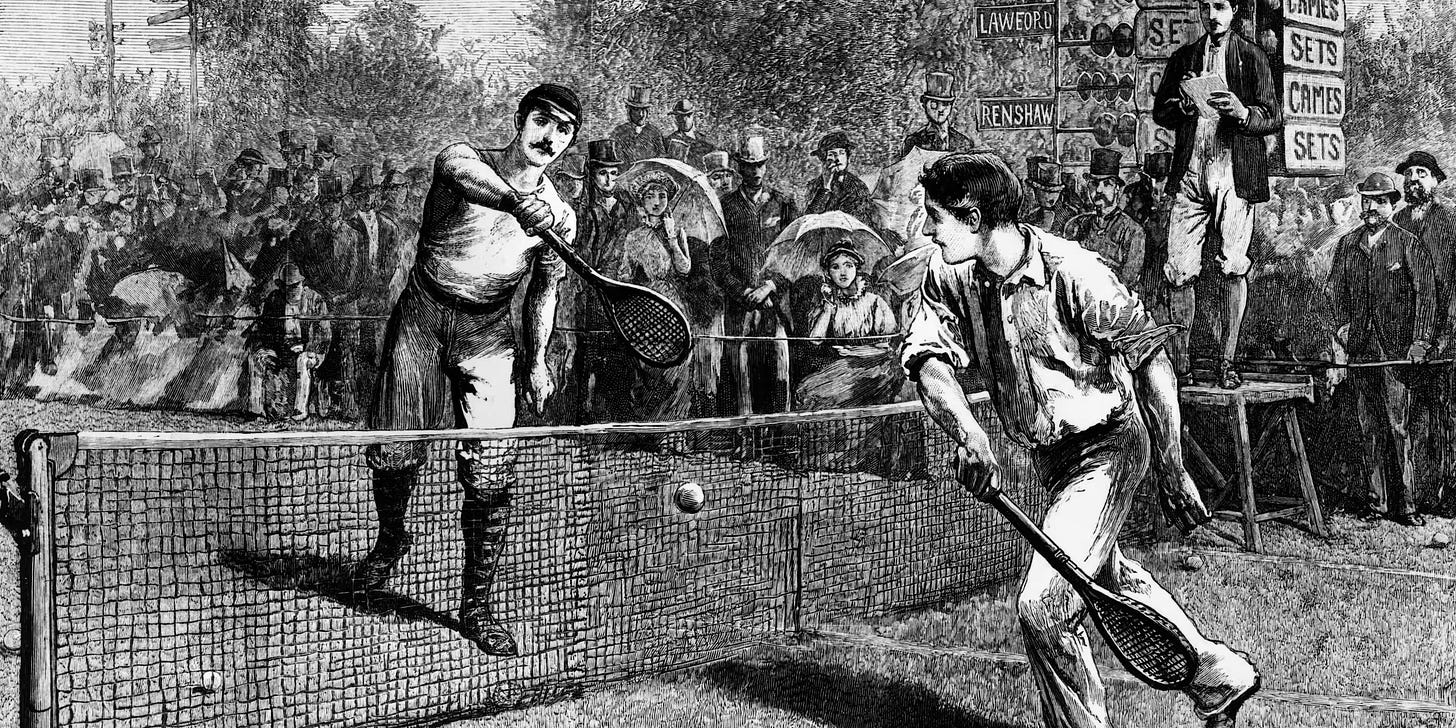

On July 9, 1877, a tennis ball was struck on a repurposed croquet lawn in South London, and history was quietly made. It did not arrive with grandeur or great fanfare. There were no royal boxes or camera lenses hunting for celebrity expressions. Just a modest court, a group of curious spectators, and a man named Spencer Gore, who became the first Wimbledon champion in front of barely 200 people.

It began with need, not ambition. The All England Croquet Club was struggling. Membership was waning, enthusiasm was drying up, and even their equipment was breaking down. Chief among these issues was a broken pony roller, essential for maintaining the lawn. It was this simple inconvenience, more than any grand design, that led to the launch of the tournament that would become the most prestigious tennis event in the world.

Roots in Ancient Palms and Inventive Pioneers

Long before the name Wimbledon became synonymous with strawberries, tradition and Centre Court drama, tennis had murky beginnings. It evolved from a 12th-century French game called jeu de paume, where monks swatted balls with their hands across drawn lines on monastery floors. This eventually developed into tenez, meaning “take heed,” as rudimentary rackets and rules took shape.

Centuries later, as aristocracy embraced the sport and monarchs like Henry VIII had courts built in their palaces, it retained an elite, almost ceremonial character. But by the 1800s, England was beginning to shift. Leisure was no longer the privilege of a few. Lawn tennis, in particular, was bubbling into something altogether more democratic.

It was Major Walter Wingfield who tried to shape it into a product. He invented a portable court set and tried to sell it under the name "sphairistikè", a word lifted from Greek to lend it ancient nobility. The idea was ambitious, even if the name was destined for obscurity. What mattered more was that the game could now be played in gardens and public parks, by men and women alike, with a racket in one hand and modern aspiration in the other.

July’s Lawn, Gore’s Swing and a Turning Point

Wimbledon’s first tournament began as a fundraiser. The croquet club needed money to replace the broken roller, and one enterprising member floated the idea of a lawn tennis event. Entry was a guinea. The prize was a modest silver cup and 12 guineas. It was barely enough to raise an eyebrow in the sporting circles of the day.

But as Spencer Gore walked onto the court that afternoon, he embodied more than skill. He brought legitimacy. A man who had once questioned whether lawn tennis would last beyond a summer was now the first to taste triumph on that hallowed patch of grass.

The match itself, by modern standards, was crude. Wooden rackets vibrated painfully through wrists. Rules were being interpreted in real time. Even the court dimensions lacked consistency, with players sometimes having to adapt between matches. Yet there was rhythm, competition, and above all, spectacle. The crowd leaned forward, instinctively sensing that something more than a fundraiser was unfolding before them.

By the end of the tournament, the All England Club had its funds, its roller, and most importantly, its purpose. Lawn tennis had found a proper stage.

One Decision that Changed Everything

In the weeks following the first final, the club’s organisers held a meeting. They debated everything from Gore’s attacking play to the confusion over scoring and inconsistent court sizes. What emerged was not just a tidy set of regulations, but the vision of an annual tournament. They even agreed to add a women’s competition in the near future, a decision that felt radical at the time.

That foresight, born from necessity, was Wimbledon’s true foundation. It wasn’t just about codifying rules, it was about creating a stage that could last. Over the decades, the grounds expanded from a croquet patch to a 42-acre complex with retractable roofs and courts that now welcome half a million spectators each summer.

Yet the essence remains rooted in that simple beginning. A broken tool, a risky idea, and the resolve of a few men who saw beyond the fading grip of croquet.

What Wimbledon Teaches Us About Legacy

Wimbledon’s rise tells us something deeply valuable about how sporting institutions are born. Not through glossy brochures or marketing campaigns, but through impulse, passion and problem-solving. The All England Club didn’t set out to create a global tradition, they set out to fix a lawn. But their actions reflected something timeless in the British character: to make do, to experiment, and if all else fails, to put on a tournament.

The story of 1877 reminds us that greatness rarely announces itself. Sometimes it wears worn-out shoes, swings a wooden racket, and plays in front of a handful of schoolchildren. But give it room to grow, and it may just become a cathedral of sport.

Even now, with its immaculate lawns and royal patronage, Wimbledon never feels like a manufactured spectacle. It still retains the charm of its accidental beginnings. The ball still bounces off grass, the crowd still holds its breath, and in every serve there is a little echo of Spencer Gore's first swing.

On this day, back in 1877, it all started with a broken roller. We’ve come a long way.