On This Day in 1854: Eureka Lit a Fire That Still Shapes Australia

How a short, desperate clash on a dusty Victorian field became a symbol of democratic courage.

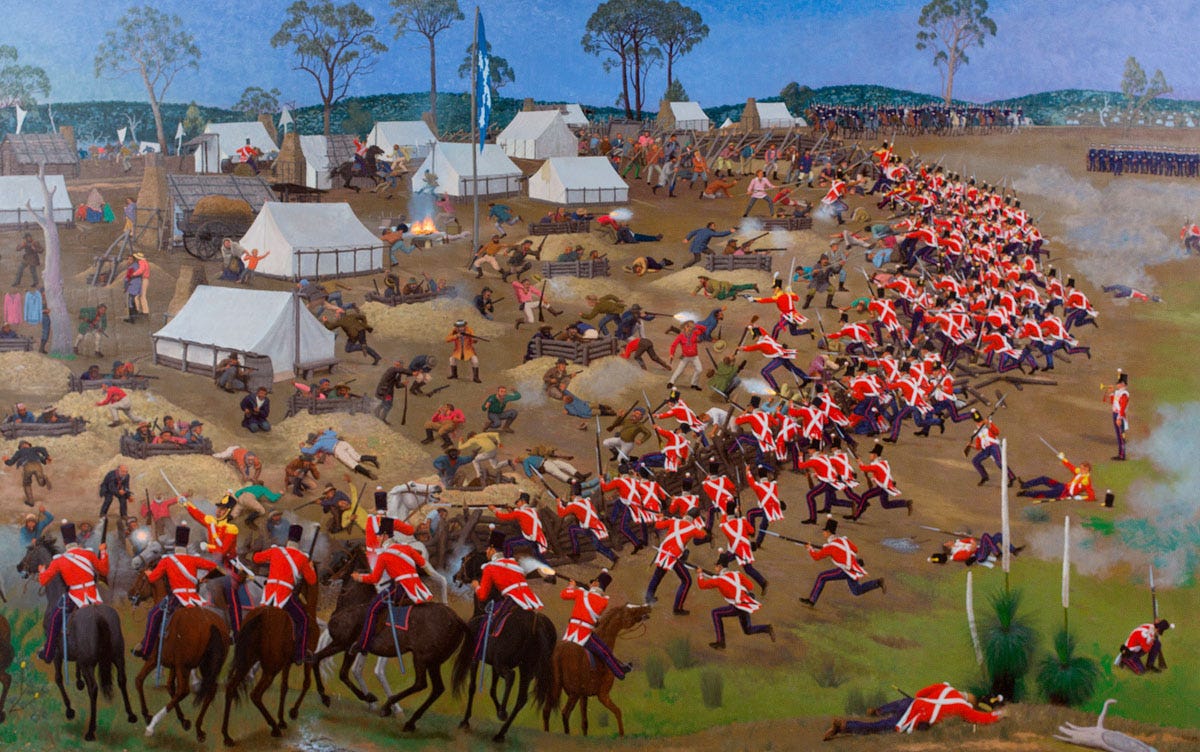

Every so often, history offers a moment that looks minor at first glance, a skirmish rather than a saga, yet charged with something far greater. On this day in 1854, the Battle of the Eureka Stockade erupted in the early light at Ballarat in the British colony of Victoria. The fighting lasted only minutes. What survived was not the barricade of timber and carts, but the conviction that people pushed to the edge will fight for dignity, fairness, and the right to be heard.

As a writer drawn to the pulse of the past, I see the story of Eureka less as a military clash and more as a test of principles. It was a moment when untrained miners, tired of being treated as pawns rather than citizens, took a stand that still speaks to us. The ground beneath the stockade may have been rough and temporary, yet the ideals tested there proved far more durable than the wooden poles hammered into that hillside.

Rising pressure in the gold fields

By the middle of the 1850s, Victoria had become a magnet for hope. The gold rush pulled in thousands, each man chasing the dream of one lucky strike. But the rush also exposed the worst of colonial administration. Miners paid a monthly licence fee whether they found gold or not, and officials enforced this rule with a mixture of corruption and brute force. The fee itself could shift depending on who demanded it. There were no voting rights for ordinary diggers and no political representation to challenge any of it.

Taxation without representation is a phrase that has echoed across history for good reason, and its bite was felt sharply in the gold fields. Men were beaten for lacking papers. Some were targeted despite official exemptions. When a miner was beaten to death, and the investigation collapsed into a cover-up, the community’s patience finally snapped. The burning of the local hotel linked to the killing was a raw explosion of anger, a symbol of people who had been pushed too far and no longer trusted official justice.

Peter Lalor and the call to stand firm

From this growing unrest stepped Peter Lalor, a young prospector who had arrived in Australia in search of fortune but instead found a cause worth far more. He had no grand ambitions at first, but the miners recognised in him a steadiness they needed. When he addressed the assembled diggers at Bakery Hill, rifle raised, his message was unvarnished. They had endured enough. They faced corruption, brutality and a licence system shaped to punish the poor while the wealthy held the vote. Their petitions had been dismissed. Their appeals ignored. If they lacked guns, they would use tools. If they lacked training, they would rely on unity.

His call carried weight because it was grounded in the everyday reality of the miners. They were not agitators by trade. They were workers tired of being treated as second-class. They followed Lalor to the edge of Eureka and built a makeshift fortress from timber, carts and sharpened poles. It was crude, but it represented something vital, a line they refused to retreat from any longer.

Not all miners agreed on every detail, especially when political overtones surfaced. Yet enough of them recognised that stepping back only invited more abuse. They chose instead to stand beside one another, even though they knew the risk.

Courage, failure and what followed

The stockade was far from a fortress. Lalor introduced a password in an attempt to secure the camp, a decision that drove uncertain men away on the eve of battle. By dawn on 3 December, the defenders numbered perhaps a hundred. The soldiers marching toward them were trained and disciplined. The miners were anything but.

When a single shot broke the morning silence, the colonial forces responded with a volley that swept through the barricade in a brutal surge. The fighting lasted only a few minutes. Lalor was badly wounded and lost an arm. More than twenty miners were killed. Over a hundred were taken prisoner. For all the talk of rebellion, this was little more than the desperate stand of ordinary workers who had run out of peaceful options.

Yet the aftermath revealed something remarkable. The public saw the heavy handed response for what it was, a striking mismatch between authority and the grievances of the diggers. When the arrested leaders faced trial for high treason, juries refused to convict. The colony recognised the injustice, and the government found itself forced to confront the failings that had provoked the uprising.

Within a year, the mining licence was abolished and replaced with a more reasonable system. Voting rights widened. Representation followed. Lalor himself entered the Victorian Parliament, a living reminder that the stockade had never been about breaking the colony apart, but about building a fairer one.

Why Eureka still matters

Eureka was not a neat victory. It was a messy, painful, human event shaped by frustration, miscalculation, bravery and loss. The miners did not win the battle in any conventional sense. They won something more important. They exposed a system that had forgotten its duty to the people it governed. They proved that when a government denies fairness, ordinary citizens will eventually push back.

On this day in 1854, for a brief moment on a windswept field, miners with little training and few weapons forced a powerful administration to face its own corruption. Democracy in Australia did not begin with fine speeches in grand halls. It began with workers behind a wooden stockade, tired of being dismissed, ready to defend their rights in the only way left to them.

Their courage helped shape a nation, not because they were flawless, but because they were human, determined and unwilling to endure injustice without protest. That is why Eureka still matters. It reminds us that democratic rights are not handed down. They are earned, defended and carried forward by those with the least to gain and the most to lose.