On This Day in 1811, Jane Austen Took Her Shot

Jane Austen risked everything to publish Sense and Sensibility, and changed English literature in the process.

A Quiet Revolution in Print

On 30 October 1811, Jane Austen opened a blue hardback book and saw her name on none of its pages. The novel was Sense and Sensibility, printed at her own expense, authored anonymously by “a lady” and released into a world where women were expected to marry, not publish.

This was no casual venture. It was a high-stakes gamble made by a woman who had already turned down marriage, lost her father, and spent years watching her work sit idle on publishers’ shelves. Yet when that first print run sold out and the reviews began to praise her wit and insight, it was clear that something rare had happened. Austen had forced open a door that society had done its best to keep shut. She had published on her own terms and proved that a woman could write, sell and succeed, even without the approval of a man.

Choosing the Pen Over the Ring

Jane Austen was not driven by fantasy. She knew the limits placed on women. She lived them. Her own life offered the outlines for the very stories she would write. Early heartbreaks, financial uncertainty, and the burden of being born clever in a world that punished female intellect were not abstract themes, they were her daily reality.

At 27, she accepted a marriage proposal from Harris Bigg-Wither, a secure match that would have guaranteed financial stability. She changed her mind the next day, walked out of the house and left behind what may have been her last socially acceptable opportunity for marriage.

She was not swayed by romance. Nor was she rejecting companionship for the sake of some lofty cause. She understood exactly what marriage would mean. It would take her time, her focus and her freedom. If she married, she would not write. And if she could not write, then what was left?

Turning down that proposal meant walking into an uncertain future. She had no career, no husband and little money. But it also meant she was free. Free to think, to imagine and to rewrite her own story in the pages of fiction.

Years of Silence, Then a Breakthrough

By 1811, Austen had been writing for well over a decade. She had penned Eleanor and Marianne in her early twenties, a novel that would later become Sense and Sensibility. It sat in a drawer for years. A second manuscript, First Impressions, would later become Pride and Prejudice. A third, Susan, was sold to a publisher who never released it.

Her father acted as her literary agent at first, sending anonymous manuscripts to publishers. When he died in 1805, that support vanished. She was forced to pause her writing while the family faced real financial strain. A manuscript that had once been promised to print remained locked in legal limbo, and Austen had no power to reclaim it.

Only when her brothers stepped in did things begin to shift. Edward offered her a cottage on his estate. Henry became her new agent and approached publishers with her earlier work. Thomas Egerton agreed to take on Eleanor and Marianne and, sensing its renewed relevance, Jane reworked it and gave it a new title, Sense and Sensibility.

This time, she was not going to let someone else decide her fate. She paid for the printing herself, sinking more than a third of her household’s annual income into the first edition. It was not just a personal risk, it was a financial one. If the book failed, the consequences would be shared by her entire family.

The Power of Her Voice

The novel succeeded. Reviews praised it. Copies sold. Austen’s voice, precise and merciless in its social commentary, had found its audience. Readers saw themselves in the Dashwood sisters, in their heartbreaks, compromises and quiet rebellions. Austen’s characters were not dreamers or damsels. They were survivors.

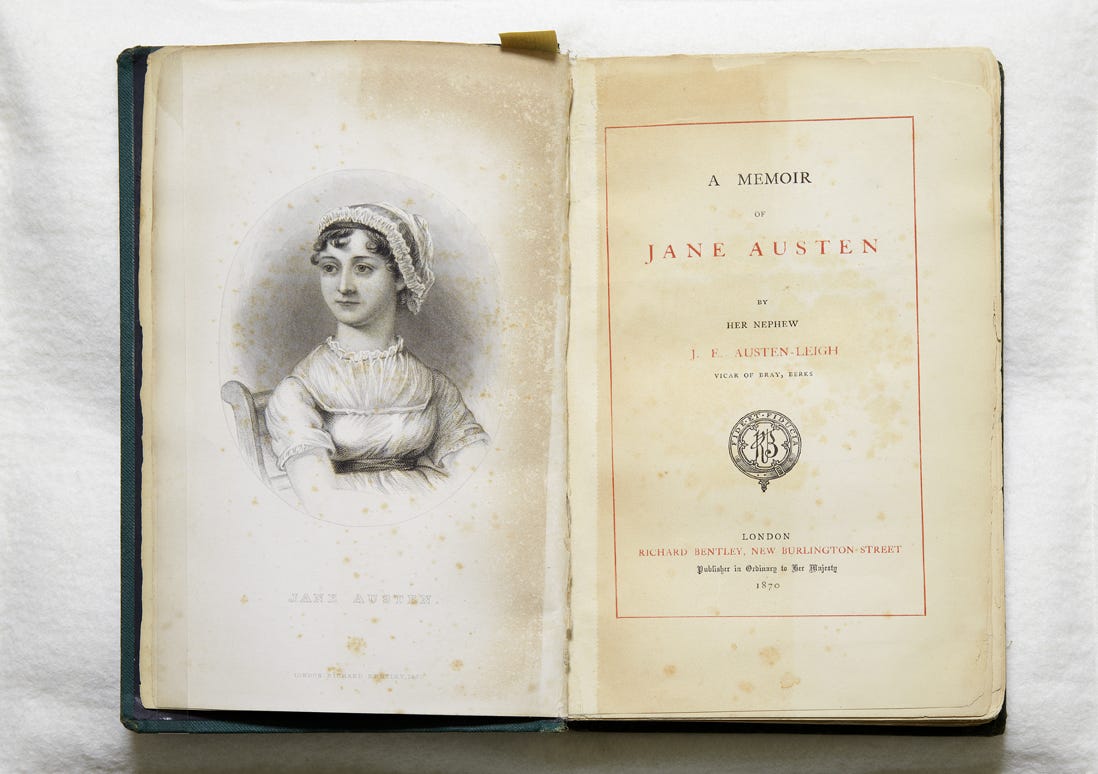

But few knew the truth. The name on the cover was no name at all, just “a lady.” In public, Jane Austen remained invisible. To protect her family’s reputation, she stayed behind the curtain, letting her work speak while she remained silent.

That silence was not weakness. It was strategy. Austen knew how society worked, and she knew how to play the long game. Once she proved her worth, she could demand more. And she did. Pride and Prejudice followed in 1813, Mansfield Park in 1814, Emma in 1815. All published in her lifetime, all released to critical acclaim.

By the time of her early death in 1817 at just 41, she had become one of the most quietly influential writers in Britain. Three more novels were published after her death, including Northanger Abbey, the book once known as Susan, now finally bearing the name of its true author.

A Decision That Echoes Centuries Later

What began on this day in 1811 was more than a book launch. It was a shift in literary culture. Austen’s decision to reject marriage and commit to authorship opened the way for generations of women to write professionally. She showed that it was possible to produce serious, lasting work in spite of poverty, despite obscurity and against the weight of social expectation.

Her stories were about love, but they were never love stories in the traditional sense. They were about choice, about dignity, about finding a voice in a world that tried to muffle it. That voice still speaks. Her novels are studied, adapted and quoted to this day because they are not relics, they are reflections.

On 30 October 1811, Jane Austen did not just publish a book. She claimed a future. Not only for herself, but for every writer who came after her and refused to be silent.