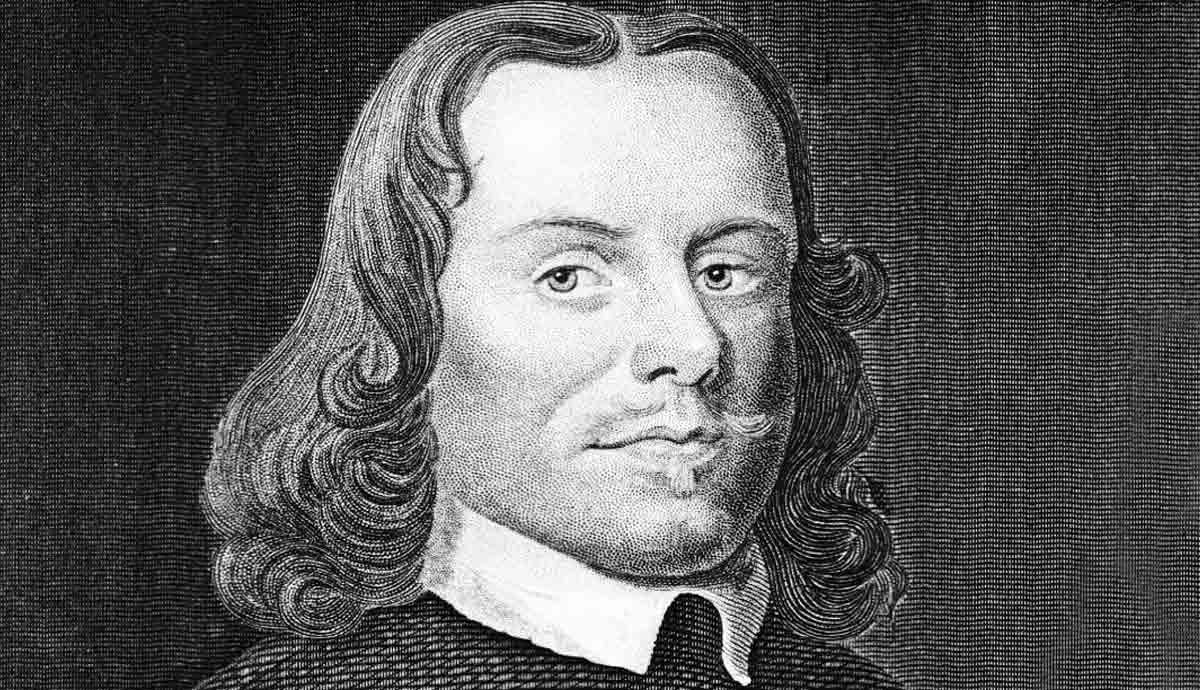

On This Day in 1660, John Bunyan Was Arrested and Gave the World a Masterpiece

From quiet defiance to literary triumph, how a Bedford preacher turned prison into purpose

I grew up just a couple of miles from the John Bunyan Museum in Bedford. As a boy, around 10 years old, I visited it on a school trip, shuffling through its solemn halls, surrounded by classmates who were probably more interested in packed lunches than in Puritans. But something stuck with me. The statue in town, the stories of sermons and prisons, the weight of principle in a man most had never heard of.

That trip didn’t feel monumental at the time, but it lit a spark. Bunyan became the first historical figure I really thought about. Not because he was a king or a warrior, but because he held the line. He stood firm when the world told him to fold. Years later, that story still resonates with me more than most.

And it all pivoted on one cold November day.

On 12 November 1660, John Bunyan was arrested for doing what he had always done, preaching without permission. What the authorities meant as punishment became the foundation of a legacy that would outlast monarchs and empires.

A Preacher Caught in a Power Struggle

The England of 1660 was full of noise. The monarchy had been restored. Charles II was back on the throne and people were desperate for stability after years of civil war and Cromwell’s republic. But beneath the street celebrations and choruses of “God Save the King,” a darker truth simmered for dissenters and nonconformists.

Before the king’s return, Bunyan had been free to preach in local churches, gather small congregations and follow his faith without interference. That freedom vanished overnight. Anglicanism was re-established. Worship outside the state church became illegal again. Suddenly, men like Bunyan were not just preachers, they were lawbreakers.

He was warned. Friends told him about the warrants. His wife, Elizabeth, urged caution. But Bunyan believed that obeying God mattered more than obeying Parliament. And so he travelled that day to a farmhouse, Bible in hand, heart steady, even though he suspected what might happen. Before he could speak a single word to the small group waiting to hear him, the authorities arrived. He was arrested on the spot.

He would remain in jail for twelve years.

Ink Instead of Voice

Bunyan’s imprisonment might sound romantic now, but the reality was bleak. His wife was left to raise their children alone, including Mary, his blind daughter. She was also pregnant and would suffer a miscarriage while dealing with the stress of John’s trial and absence. Elizabeth campaigned hard for his release, knocking on doors, petitioning judges, facing the indifference of a system that saw her husband not as a threat, but as a nuisance to be contained.

And yet, behind those prison walls, Bunyan’s true work began.

He could no longer preach with his voice, so he turned to the page. He began with Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, a raw, confessional account of his journey from sin to salvation. But his imagination reached further. He began building an allegory, piece by piece, inspired by his own trials and theological convictions. He created a world where Christian, an everyman figure, journeys from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City, facing temptation, fear and doubt at every step.

That work became The Pilgrim’s Progress. It wasn’t penned in ideal conditions or refined by tutors. It was carved out of time stolen from squalor and hardship. And it spoke to people because it was written by someone who had lived what he wrote.

A Legacy Forged in Chains

When Charles II softened his stance in 1672 and issued a Declaration of Indulgence, Bunyan finally walked free. He carried with him the draft of the book that would change his life, and change English literature.

The Pilgrim’s Progress was published in 1678. It exploded in popularity. Bunyan, the uneducated tinker from Elstow, became one of the most read authors in the English-speaking world. His work would travel to the American colonies, into Europe and beyond. It would be translated into over two hundred languages. For many generations, it was said that the only book more widely owned in English homes than The Pilgrim’s Progress was the Bible itself.

What made the book so enduring wasn’t just its religious message, but its clarity, its emotion, its resonance. It wasn’t written for scholars or kings. It was written for ordinary people navigating their own journeys through hardship and hope. It showed that belief, when tested, doesn’t break. It transforms.

Writers from Charles Dickens to Charlotte Brontë, from C.S. Lewis to John Steinbeck, would later draw from Bunyan’s form and symbolism. He paved the way for the English novel, and did so from a prison cell.

Why November 12th Still Matters

On this day, 12 November, we remember more than an arrest. We remember a decision. Bunyan could have taken the easy way out. He could have agreed to stop preaching and walked free. But he didn’t. He stood still while the world told him to move.

His story has always stayed with me. Maybe because I first heard it so close to where it happened. Maybe because I walked some of the same streets he did. Or maybe because there’s something timeless about what he did. He chose to suffer for something he believed in, and he turned that suffering into something eternal.

We often celebrate the loud heroes of history. The generals, the kings, the revolutionaries. But John Bunyan’s legacy came from quiet defiance. He didn’t shout. He wrote. He didn’t rebel with weapons. He did it with pages and faith.

That’s why his arrest on this day in 1660 should never be a footnote. It was the day a man’s silence was used to build something louder than any sermon.