On This Day: A Crown, a Rocket, and the Eyes of the World

From royal vows to the stars above, two moments that made the world stop and look up

It was the sort of day that even time seemed to pause for. A day stitched together by pomp and progress, watched from palace gates and television sets alike. On 29 July, history did what it often does when we least expect it, writing two very different chapters that, strangely, shared a similar theme. One was wrapped in lace and royal promise, the other launched by wires and ambition, aimed squarely at the sky.

One moment belonged to a fairy tale. The other was all science fiction, becoming science fact. I was not yet born for either, but their shadow reached all the way into my own childhood and beyond.

Diana, Charles, and a Wedding That Touched the Clouds

By the time I came along in 1981, this story had already been set in stone. Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer had tied the knot on this very day at St Paul’s Cathedral in London, with all the bells and whistles only a royal wedding could summon.

I was born later that year, so I cannot tell you what it felt like in the moment. But I can tell you that, growing up, you did not need to have seen it live to know what it meant. The footage lived on in reruns, documentaries, school projects and even biscuit tins. Diana became part of the fabric of Britain, and it all began with that wedding.

The numbers remain staggering even now. Over 750 million people watched across the globe. In a pre-internet world, that figure speaks to the sheer weight of public curiosity and royal enchantment. It was more than a ceremony. It was a broadcast of British identity, a show of tradition that stood up straight and waved to the cameras.

The pomp was immense. Streets lined with flags, choristers hitting notes that echoed beyond the walls of St Paul’s, and a bride in a silk gown with a train that went on longer than some family trees. The Archbishop of Canterbury declared it a marriage that would inspire fairy tales. The fairytale language became so deeply woven into public discourse that it seemed almost scripted. Yet, beneath it all, there was a human tale of two people, suddenly expected to embody centuries of expectation.

In hindsight, we know the story did not stay wrapped in romance. But that moment on 29 July 1981 was a still frame, pure and untouched by what would follow. In that instant, Diana became not just a princess, but a symbol of something Britain longed for. Youth, beauty, vulnerability and grace, captured live and sent into homes from Aberdeen to Adelaide.

As a child of the 80s, Diana was everywhere. Her face was in every magazine, her smile made headlines on its own, and her presence often felt closer than the royals who came before her. She did not just modernise the monarchy, she humanised it, even if the price was steep.

That wedding, though, remains the lens through which the public first truly saw her. And it happened on this day, all the way back in 1981.

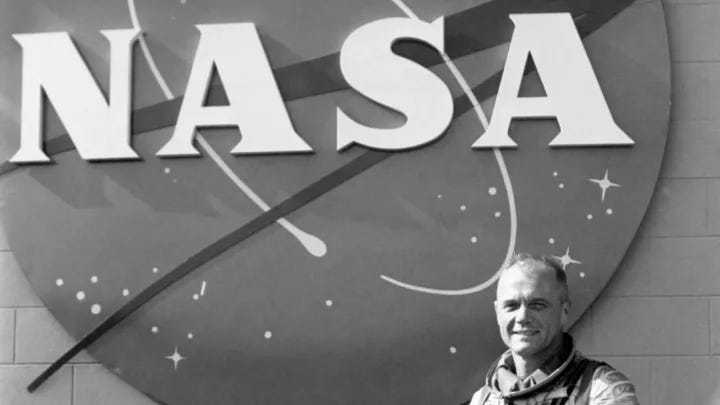

NASA: Born of Urgency, Raised by Curiosity

If 1981 gave us a royal wedding, then 1958 handed the world something with far less lace and far more lift-off. On 29 July of that year, the United States government formally established NASA, and with it, opened the door to a new kind of destiny.

I would not be born for another 23 years. But when I did arrive, space had already become part of the ordinary. Shuttle launches were on the telly, the moon landings had moved into the history books, and Star Wars had turned astronauts into icons. Yet none of it would have been possible without what happened on this day in 1958.

NASA was not born out of calm reflection. It was forged in the heat of the Cold War, lit by the fire of fear and competition. The Soviet Union had launched Sputnik into orbit in October 1957, and with it came a wave of panic across the Atlantic. The idea that the USSR had beaten America to space stirred not just pride, but fear. If they could put a satellite above your head, what else could they do?

Congress acted swiftly. The National Aeronautics and Space Act was signed into law, and NASA officially opened for business. The goal was clear. America needed to catch up, then lead. The result was not only a space race, but a cultural one too. NASA became a symbol of what the United States wanted to be seen as: pioneering, fearless, and brilliant.

Of course, NASA did not launch men into space overnight. But the act itself created the agency that would one day send Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins to the Moon. It would produce the Voyager probes that are still sailing through the void, and the Hubble Space Telescope that changed how we look at the universe.

It was never just about rockets. It was about the belief that science could shape the future. NASA’s formation formalised that idea. And while its roots may have been tangled in geopolitical urgency, its fruits have been shared by all of us.

Even as a child watching grainy lift-offs on a classroom television, I knew this was different. These were not cartoons or actors, these were real people leaving Earth behind. And they did so because, on 29 July 1958, somebody signed a piece of paper that said we should try.

Two Threads, One Date

There is something rather poetic about the fact that these two events happened on the same day, albeit years apart. One rooted in tradition, one reaching into the unknown. One looked back at centuries of royal custom, the other tilted forward into the cosmos. But both captured the world’s attention. Both made people stop what they were doing and look up, whether at a cathedral ceiling or a rocket trail.

For all the differences between a royal wedding and the birth of a space agency, there is a shared understanding that these moments matter. They set the tone. They inspire. They become reference points, not just for nations but for individuals. People remember where they were. Or, if like me, you were not yet here, you grow up feeling as though you were.

In 1981, millions dreamed of fairy tales. In 1958, they began building machines to chase the stars. Two very different dreams, and yet, on this day, both came to life.