On This Day 29 August 1533: The Fall of the Last Inca Emperor

When ambition, betrayal and pieces of silver and gold reshaped an American empire

History is rarely gentle with those who trust in promises. On this day, 29 August 1533, Atahuallpa, the last sovereign Sapa Inca of the greatest empire in pre-Columbian America, was executed by the Spanish conquistadors. His captors had promised him freedom. Instead, they took his gold, melted it into bars and strangled him in the main square of Cajamarca. It was not just a man who died that day. It was an empire, an identity, and an entire way of understanding power.

Atahuallpa's fall remains one of the most devastating episodes in the European conquest of the Americas, and arguably the most cynical. In his demise, we find not simply the spoils of a bloody collision between worlds, but the quiet horror of realising too late what kind of enemy you are truly facing.

Power Vacuums and Plague: A Collapsing World

By the time the Spanish reached the highlands of what they called Peru, the Inca Empire was in tatters. It had been one of the most sophisticated and expansive civilisations in the Americas, stretching across the Andes with meticulously engineered roads, complex statecraft and an imperial cult that made the Sapa Inca not just a monarch, but a living deity.

But fate had already opened the gates long before the Spaniards arrived. Smallpox, a disease the Inca had never encountered, arrived ahead of the European soldiers and devastated the population. It claimed the life of the Sapa Inca Huayna Capac and his heir, leaving two younger sons, Atahuallpa and Huáscar, to battle for control of the throne. The ensuing civil war broke the Inca world from within.

Atahuallpa emerged victorious, capturing and reportedly executing his brother, but the empire was bruised, bloodied and fractured. The timing could not have been worse. As Atahuallpa consolidated his fragile victory, Francisco Pizarro and his band of fewer than 200 men entered the Andes, driven by visions of gold, imperial ambition and a deeply embedded belief in European supremacy.

Pizarro's arrival was not met with immediate resistance. The Spanish were seen more as curiosities than threats, strange figures on strange beasts with thunderous weapons and unfamiliar gods. It was that blend of novelty and timing that gave the conquistadors their opportunity. But it was deception that secured their victory.

Gold for a God: The Greatest Ransom Ever Paid

On 16 November 1532, Atahuallpa agreed to meet the Spanish in the town square of Cajamarca. He came not with weapons but with ceremony, his bearers lifting him high on a litter decorated with feathers and precious metals. He was accompanied by thousands of men, but none armed for war. To the Inca mind, this was a meeting of diplomacy, of ritual acknowledgement.

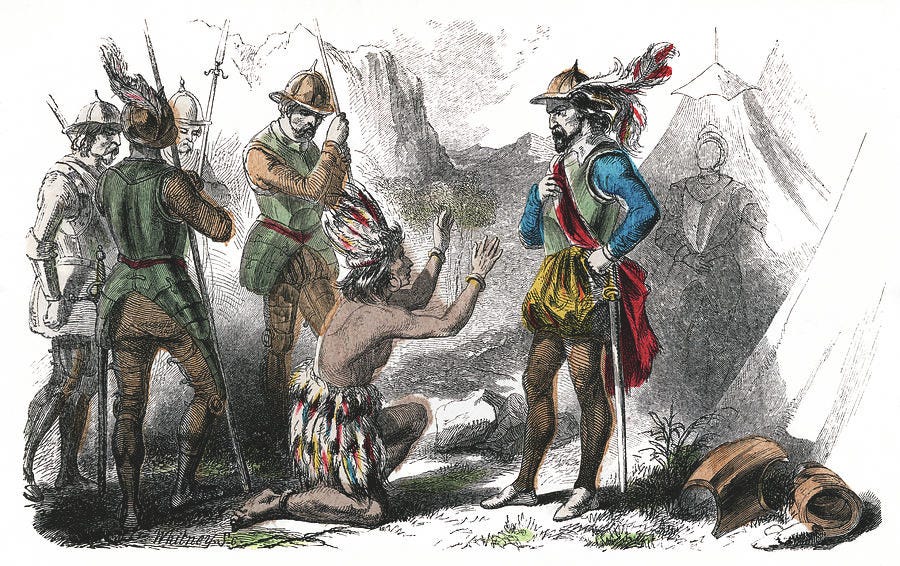

To Pizarro, it was a moment of surgical strategy. He had set a trap. As a Dominican friar approached the Inca leader and demanded submission to the Christian faith and the King of Spain, Atahuallpa refused and discarded the Bible he was handed. That symbolic act gave Pizarro the pretext he needed. The Spanish opened fire, slaughtering the unarmed retinue with cannon, sword and mounted cavalry. Within hours, thousands lay dead. Atahuallpa was taken prisoner.

What followed was the ultimate indignity of a leader trying to negotiate his own survival with those who had no intention of honouring terms. Atahuallpa offered a ransom that remains astonishing even by today’s standards. He promised to fill a room, over 6 metres long and 2.5 metres high, with gold—and to fill it twice more with silver. The Spanish agreed.

For months, caravans of treasure poured into Cajamarca. Temples were stripped, ornaments dismantled, sacred icons melted down. Historians estimate the total weight of the ransom at around 24 tons of precious metal—most of it melted into ingots to ease transport back to Spain. But wealth did not buy Atahuallpa his liberty. It only proved how much more there was to take.

A Broken Bargain and a Manufactured Trial

As Atahuallpa waited for his release, he played politics from his prison. He tried to maintain his influence over the fractured empire, and when it became clear his brother Huáscar might still be seen as a threat to his rule, he arranged for his death. That decision would become the Spanish excuse for turning against him. Though the Spanish had no real interest in Inca legal traditions, they accused Atahuallpa of murdering his brother and plotting against the Spanish crown.

He was tried in a kangaroo court. Found guilty, naturally, he was sentenced to death by fire, a terrible fate for any man, but particularly appalling to an Inca, for whom the preservation of the body after death was sacred. Conversion to Christianity was offered as a means of avoiding the flames. It was a final cruelty in a long line. Atahuallpa, desperate and terrified, agreed.

On 29 August 1533, Atahuallpa was publicly strangled with a garrotte. The man who had ruled the Andes and commanded the loyalty of millions was reduced to a lifeless symbol, bound to a post, watched by men who viewed themselves as civilisers rather than thieves. His Christian name, Francisco, taken in forced baptism, was a final insult.

What Died in Cajamarca

Atahuallpa’s execution did not just remove a political figure. It destroyed the very possibility of negotiated peace. With him dead, the Spanish installed a puppet, another brother, Manco Inca, who they hoped would serve as a loyal servant of the crown. He would eventually rebel, but the damage was done. Cuzco fell. Lima rose. The Viceroyalty of Peru was born, and the Inca world receded into memory.

There is a temptation to look at this story as one of cultural collision or even conquest. But it was, more accurately, a deception wrapped in the garb of diplomacy. The Spanish were not interested in co-existence or mutual benefit. Their goal was extraction, expansion and domination. Atahuallpa’s mistake was not in fighting. It was in thinking his enemy could be bargained with.

That single misunderstanding cost him his life and his people their world.

Singular Reflection

In telling this story, I cannot see Atahuallpa as merely a fallen monarch or a tragic figure. He was a skilled strategist, a survivor of civil war, a man who understood power. But even he failed to grasp the kind of imperial ambition that arrived with the Spanish. His offer of gold, magnificent though it was, misread their motives completely.

To him, gold was a means. To them, it was the entire end.

It is not enough to say Atahuallpa was betrayed. That implies a deal gone wrong. There was no real deal. There was only a trap, sprung with patience and justified with scripture.

The fall of the Inca Empire was not a tale of military genius or religious conversion. It was a robbery in daylight, carried out under the guise of civilisation.