On This Day 2011: Fall of Hosni Mubarak and the Roar from Tahrir Square

How Egypt’s Uprising Shook a Regime and Tested the Promise of the Arab Spring

On This Day, 11 February 2011, a helicopter lifted off from Cairo carrying a man who had ruled Egypt for nearly thirty years. As it rose above the capital, the streets below heaved with celebration. The chants that had rolled across Tahrir Square for weeks had found their mark. Hosni Mubarak, soldier turned president, was gone.

It felt, in that moment, like history had broken open.

Yet revolutions are rarely neat, and rarely kind to those who believe a single resignation can mend a nation’s fractures. To understand why the Egyptian Revolution erupted, and why its aftermath proved so troubled, we have to look beyond the square and into the decades that shaped it.

Roots of Discontent under Mubarak

Mubarak came to power in October 1981 after the assassination of President Anwar Sadat. He inherited a nervous state and chose to govern through control. A state of emergency, introduced in the wake of Sadat’s killing, became the air Egypt breathed. It allowed detention without trial, curtailed protest, and muffled dissent in the press. What was sold as stability hardened into stagnation.

For years, many Egyptians endured rather than rebelled. There was fear, certainly. There was also calculation. Better the familiar hand than the unknown future. Elections were held, but they carried the weary scent of inevitability. Opposition figures were constrained by restrictive rules. Ballot boxes were dipped in ritual, not risk.

Meanwhile, the country’s social fabric frayed. Youth unemployment rose. Prices climbed. In Cairo’s crowded districts and provincial towns alike, graduates drifted without work. Families juggled shrinking wages against rising food costs. Stories of corruption were not whispers but common knowledge. Wealth gathered around those close to power, while millions scraped by.

Mubarak’s defenders pointed to order. They warned of extremism and chaos. And indeed, Egypt had known violence from militant groups. But repression bred its own bitterness. When a government insists on silence, anger simply learns to wait.

Spark from Tunisia to Tahrir

The flame that finally caught in Egypt was lit beyond its borders. In December 2010, a young Tunisian street vendor, humiliated by official harassment and stripped of his means to earn a living, set himself alight in despair. His death became a rallying cry. Protests in Tunisia toppled a long entrenched leader and showed that an autocrat could fall.

Across the Arab world, people watched. Egyptians watched.

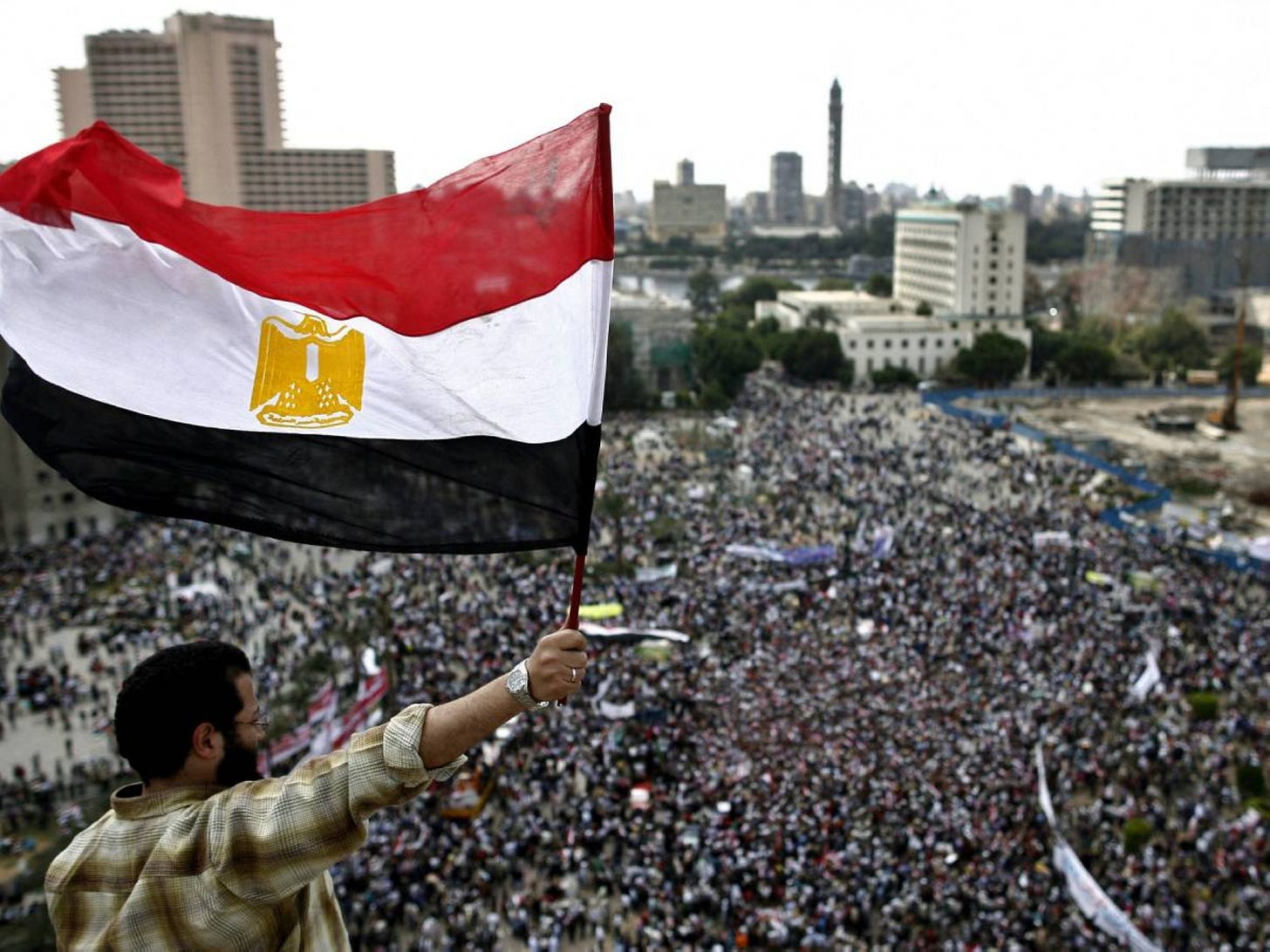

On 25 January 2011, thousands gathered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. They came from different classes, faiths and generations. Some were seasoned activists. Others had never marched before. Social media helped organise them, but the grievances were older than any platform. They spoke of dignity, of bread, of freedom. They demanded the end of a regime that had outstayed its consent.

The authorities responded as they had been conditioned to respond. Police fired tear gas. Protesters were beaten. The internet was cut. A curfew was imposed. Yet the crowds did not dissolve. If anything, they thickened. When violence escalated and snipers appeared on rooftops, the toll in blood only deepened the resolve.

Tahrir became a theatre of national reckoning. Christians formed human chains to protect Muslims at prayer. Volunteers cleaned the square. Makeshift clinics treated the injured. For eighteen days, the world watched Egypt wrestle with itself.

On 10 February, Mubarak addressed the nation. Many expected his resignation. Instead, he offered promises of reform and a vague transition. The square answered with fury. The following day, the announcement came not from the president but from his deputy. Mubarak had stepped down. Power would pass to the military council.

The eruption of joy was immediate and visceral. Fireworks split the night sky. Strangers embraced. For a people long told they were powerless, it felt like proof of their own strength.

Aftermath and Unfinished Revolution

History, though, is less interested in emotion than in consequence.

The fall of Mubarak did not dissolve the structures that had sustained him. The military, long the backbone of the state, remained central. Elections followed. An Islamist candidate from the Muslim Brotherhood won the presidency. For some, this was democracy at work. For others, it was the beginning of a new unease.

Polarisation intensified. Protests returned, this time against the elected leadership. In 2013, the military intervened and removed the president in a coup. A new strongman emerged from the ranks of the armed forces. His election delivered a result so overwhelming that scepticism was inevitable.

Civil liberties tightened once more. Critics spoke of prisons filling, of dissent shrinking back into whispers. International observers described a climate of fear. The circle, to many eyes, seemed complete.

So what, then, are we to make of 11 February 2011?

It would be easy to frame the Egyptian Revolution as either triumph or tragedy. It was both, and neither. It revealed the capacity of ordinary citizens to challenge entrenched power. It exposed the fragility of regimes that mistake longevity for legitimacy. Yet it also showed how deeply rooted systems can outlast the men who front them.

Revolutions are often judged by what follows. In Egypt’s case, the immediate aftermath disappointed many who had filled Tahrir with hope. But to measure the uprising solely by subsequent political outcomes is to miss its deeper significance.

For eighteen days, fear loosened its grip. Egyptians who had been told their voices did not matter discovered that, together, they could alter the course of their nation. That memory does not vanish, even when circumstances grow harsh again.

On This Day in 2011, a president departed under pressure from his own people. The images remain vivid, the chants still echo in archived footage. They remind us that power rests, ultimately, on consent. When that consent is withdrawn in sufficient numbers, even the most durable ruler can fall.

As a historian, I am wary of neat conclusions. Egypt’s story did not end with Mubarak’s resignation. It continues to unfold, shaped by forces both internal and external. But 11 February stands as a marker, a day when a long standing order cracked in full view of the world.

For those who stood in Tahrir Square, it was a day of vindication. For those who study history, it is a case study in the volatility of suppressed societies. And for any government that confuses control with consent, it is a warning.

The helicopter that carried Mubarak away did more than remove a man. It signalled that no tenure, however fortified, is immune to the collective will of a people pushed too far.

That is the enduring lesson of On This Day 2011.