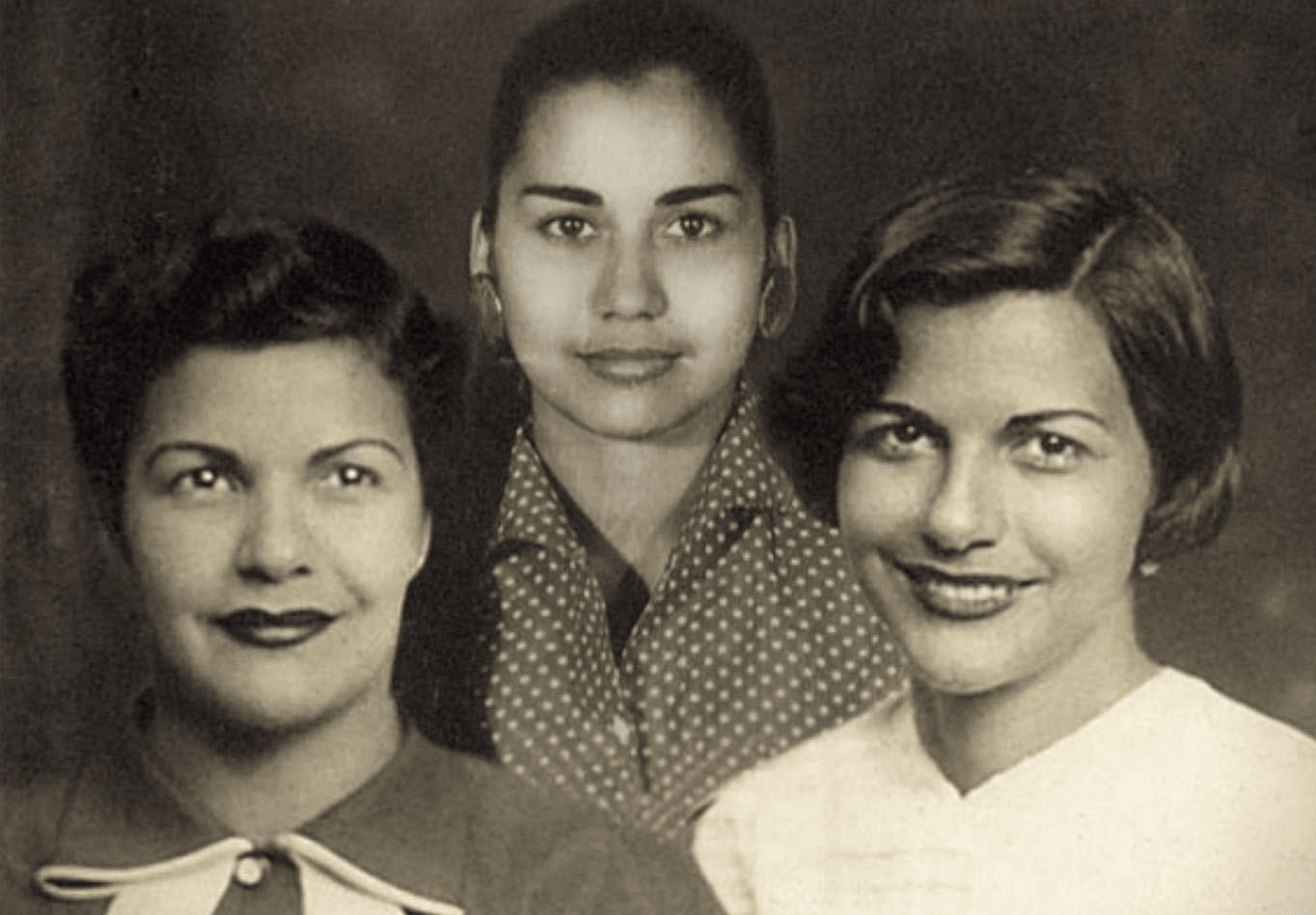

On This Day 1960: The Assassination of the Mirabal Sisters

How the Mirabal sisters turned a dictatorship’s darkest act into the spark that helped bring it down

The story of the Mirabal sisters has been told many times, yet every return to it feels like meeting raw courage at close quarters. On this day in 1960, three women were murdered on a mountain road in the Dominican Republic, and the violence meant to silence them set their legacy in stone instead.

As a history writer, I keep circling back to the same truth. Every era produces people who refuse to shrink. The Mirabal sisters chose the harder path and paid for it with their lives, yet their conviction reshaped their country. That is what matters most when we look back.

Below is my reflection shaped by their recorded history and the accounts of what happened that night, and by the deeper pattern their story reveals about how change really begins.

Roots of Resolve

Long before the rain soaked their final journey, the sisters were already marked by their refusal to bend to intimidation. Their confrontation with Rafael Trujillo began not with leaflets or meetings but with something disarmingly personal. A young woman in a garden, a dictator stepping too close, and a family making the brave decision to leave his party despite the risks.

That small act of self-respect was their first step into open conflict with power. Trujillo expected obedience, and he expected admiration. What he received from Minerva Mirabal was neither.

He retaliated with surveillance, arrest, public humiliation and relentless pressure. Her father died under that strain, and the family suffered years of disruption and harassment. Yet instead of withdrawing, their sense of purpose solidified.

This is the point that strikes me most. Dictatorships often fall not because people grow fearless overnight but because slow, grinding oppression eventually steels the very resolve it tries to break. The Mirabal sisters personify that process.

Rise of the Movement

By 1960, the sisters were no longer simply resisting for their own survival. Their homes had become nerve centres of an underground effort to loosen Trujillo’s grip. Patria Mirabal’s kitchen, once a place of domestic routine, turned into a workshop where fireworks were stripped for gunpowder and rebels were taught how to challenge a state that seemed immovable.

What the sisters offered the resistance was more than organisation. They gave it visibility and spirit. Their open defiance provided others with a symbol that life under dictatorship did not have to mean quiet acceptance.

Trujillo understood symbolism, and he feared it. He had already tried to ruin Minerva’s plans for a legal career, using bureaucracy to shut every door he could. Yet every attack on her only sharpened public awareness of his insecurities. When he targeted the sisters’ husbands, hoping to tighten the noose around them, he misjudged the moment again.

Support for the sisters grew. So did international attention and pressure from the Church at home. Trujillo had been accustomed to controlling narratives, but by then the story was slipping from his hands.

Night on the Mountain Road

And so we return to that stormy evening. A roadblock. Soldiers arriving from the shadows. Three sisters removed from a jeep and marched into darkness. The brutality was quick and cold. Their bodies were staged to mimic an accident, but the truth was obvious to the people who knew the regime’s habits far too well.

What moves me most about their final hours is not the violence but the intention behind it. It was designed to frighten. It was meant to sever a movement’s spine. Instead, it became the blow that fractured Trujillo’s remaining authority.

History has a habit of turning carefully planned acts of intimidation into their opposite. By killing the Mirabal sisters, the regime exposed its own weakness. Only a rattled dictatorship feels the need to silence unarmed women who refuse to stop speaking.

Within six months, Trujillo himself was ambushed and killed. His downfall never belonged to a single moment, but the sisters’ deaths hastened it and shaped the memory of it.

Enduring Echoes

Every country carries its own stories of defiance, yet this one resonates far beyond its original setting. On this day, the world now marks the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. It is not a coincidence. The Mirabal sisters have come to stand for more than resistance to a dictator. They remind us that violence often seeks to silence those who dare to challenge how power is used, and that memory can be a stronger force than fear.

From a historical point of view, their legacy lies in their refusal to surrender even when the cost was unbearable. From a human point of view, it lies in the unity of their actions. They stood together in life, and the world remembers them together in death.

What I take from their story is not tragedy but clarity. Change rarely arrives as a single heroic act. It builds through countless steady decisions to step forward when stepping back would be easier. The sisters made those decisions again and again. By the time the dictatorship struck its final blow, the momentum had already shifted.

Why This Story Still Matters

The temptation with history is to search for the reassuring arc. Bad men fall, brave people rise, justice steadies itself. The truth is messier. The Mirabal sisters did not live to see the country they fought for. Their courage came with no guarantee of reward.

That is precisely why their story endures. It shows that resistance gains meaning not from victory but from integrity. The sisters acted because they believed the people around them deserved dignity, safety and truth. These ambitions are not outdated. They remain the foundations of every society that hopes to call itself free.

Looking back on this day in 1960, I see three women who shaped the future of their nation by refusing to let fear define their lives. Their story invites us to look at our own time and ask where similar courage is needed, and who might be carrying it quietly until the moment demands more.

History often comes down to choices made in private places. A garden at a party. A kitchen filled with fireworks. A rain soaked road. In each setting, the Mirabal sisters chose principle over comfort. We remember them not because they were perfect, but because they were unshakeable when it mattered most.