On This Day 1956: A Leaking Boat Changed The Fate Of Cuba

How a ragged landing, a misguided plan, and a handful of half drowned rebels reshaped the modern world.

History often declares its intentions with fireworks, yet the birth of the Cuban Revolution came in the hush of a grey December dawn. Eighty-two men arrived on a battered yacht that should have carried a fraction of that number. Their boots were soaked, their rifles were useless, and their nerves had been shaken by a week of storms. If a revolution needs swagger at its starting line, this one looked more like a funeral march.

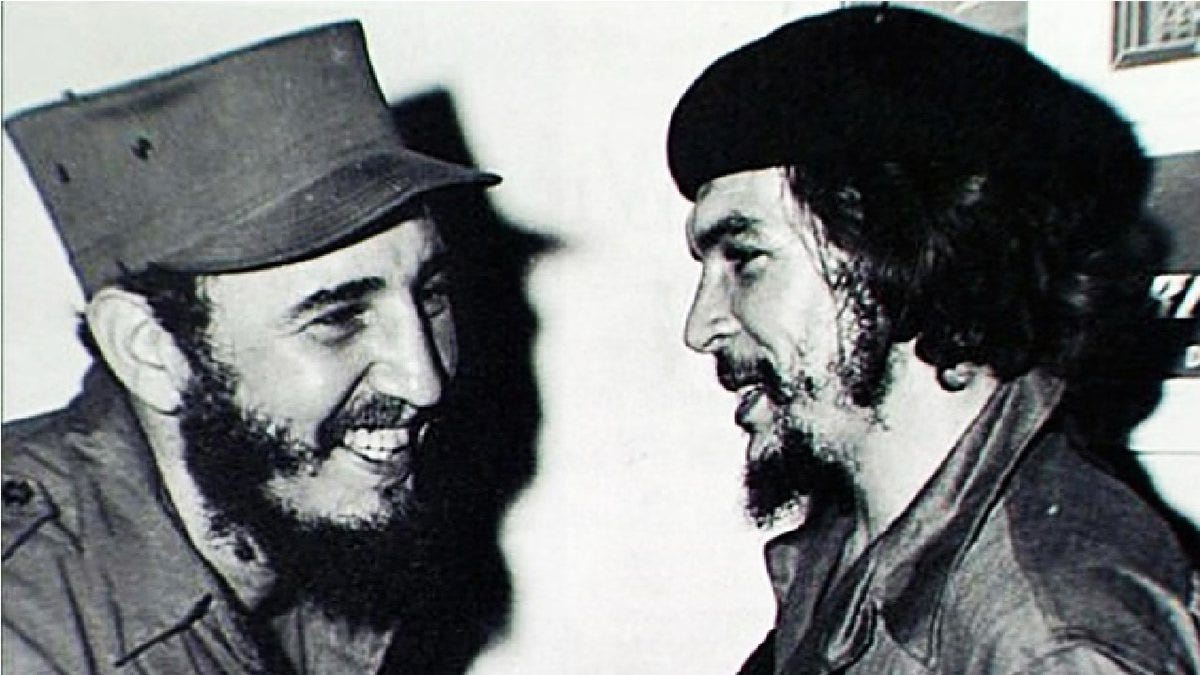

Still, the date matters. On this day in 1956, Fidel Castro returned to Cuba with a conviction that came from somewhere deeper than calculation. He had tried once already. He had been imprisoned, humiliated, exiled, and written off. I recall when I studied this many years ago that his second attempt began in conditions that would have broken most movements before they had taken a single step inland.

This misery soaked landing forces us to look again at how revolutions begin. Not with clean plans, not with neat logistics, but with people who refuse to accept the world as it stands. Castro arrived starving, sick, and already half defeated, yet the moment is still recorded as the start of one of the most consequential upheavals of the twentieth century.

Stark Realities That Built A Revolutionary Resolve

Before we reach the mangrove swamp, we have to understand the rage that carried Castro there. By the early 1950s, Cuba was ruled by Fulgencio Batista, a man whose second rise to power came through a military coup rather than a ballot box. Batista did not bother with a disguise. He ruled with a clenched fist, handled dissent with violence, and welcomed foreign money that treated Havana like a playground for anyone with cash to burn. While luxury hotels glittered, the majority of Cubans lived in poverty and watched their future shrink to a thin thread.

Castro began his political life as a young lawyer walking the streets of Havana’s working-class districts. He had studied Marx, but his complaints were shaped most of all by the faces he saw in his own country. His first great gamble took place in 1953 when he and a band of followers tried to storm the Moncada Barracks. The plan was loose, the execution was clumsy, and the rebels were cut down with brutal speed.

Yet something important survives even the worst of failures. Castro used his trial to attack Batista’s rule, and the public listened. The phrase he delivered then, that history would absolve him, became both shield and prophecy. When Batista freed him under pressure, Castro left for Mexico but carried his purpose with him like a wound that refused to close.

Ragged Beginnings That Refused To Die

The journey back to Cuba in 1956 should have been the death knell for the whole movement. The yacht was too small and too fragile. Dozens were seasick. Supplies were ruined. The crossing took longer than expected, which meant their landing was days behind schedule and the government forces were already alert. When the yacht finally smashed into a swamp, the rebels had lost their equipment and most of their advantage.

Accounts of that day paint a grim picture of their first hours on land. Waist deep in mud, rifles raised above their heads, they stumbled toward the mountains with the hope of linking up with supporters. Instead they walked straight into an ambush. Jets screamed overhead, and soldiers fired from concealment. Most of the rebels died or were scattered, and even Che Guevara was hit in the neck. Twenty survivors remained. Twenty out of eighty two.

I find this moment fascinating because it reveals a truth that often hides behind the grand sweep of history. Revolutions do not depend on perfect conditions. They depend on people who do not leave, even when everything around them tells them to run. Castro and the remnants of his force hid in the countryside and found shelter with local farmers. They had no right to imagine they could still shape the destiny of a nation, yet that belief hardened in the mountains. In those early weeks, when they were starving and hunted, they constructed the foundations of the guerrilla movement that would eventually topple Batista.

What stands out is not the heroism, but the stubbornness. Every rational calculation said the revolt was finished. Instead, it began again with a handful of men who had already seen their comrades fall. There was no romantic gloss. The revolution endured because its participants kept going long after circumstance had tried to silence them.

Long Shadows Of A Single December Morning

By 1959, Batista fled, and the rebels walked into Havana not as fugitives but as victors. The world soon felt the consequences. Castro’s Cuba aligned itself with the Soviet Union, and the Cold War shifted into the Americas. Later decades followed with repression, propaganda, and an iron-handed rule that left many Cubans without the freedoms the revolution had promised.

When I look back at that swamp landing, I see not just the rise of a revolutionary figure but the complicated origins of a chapter that reshaped global politics. Revolutions rarely give the clean outcomes their early supporters hope for. They set off a chain of events that ripple through generations. Castro’s legacy is a battlefield of opinions, and his government left deep scars that cannot be dismissed.

Yet the significance of the day remains. On this day in 1956, the Cuban Revolution began with more misfortune than momentum. It began with hunger, confusion, and the near extinction of the force that claimed to speak for the country’s future. That thin moment, when everything seemed lost, grew into something much larger and far more unpredictable.

As a historian, I am drawn to moments like this because they remind us how much of the past is carried by ordinary human limits. Tired feet, empty stomachs, improvised plans. These details matter because they remind us that history is not made by symbols. It is made by people who are frightened, flawed, and often fumbling toward a goal they cannot yet see clearly. Castro’s arrival on Cuban soil in 1956 shows how frail the beginnings of world-changing events can be.

This is why I mark this date. Not to glorify the revolution, nor to excuse what followed, but to understand how a story that would shape continents began with a sodden march through a mangrove swamp. It is a reminder that history often grows from the unlikeliest soil, and sometimes the most unlikely groups of people carry the weight of an entire nation’s turning point.