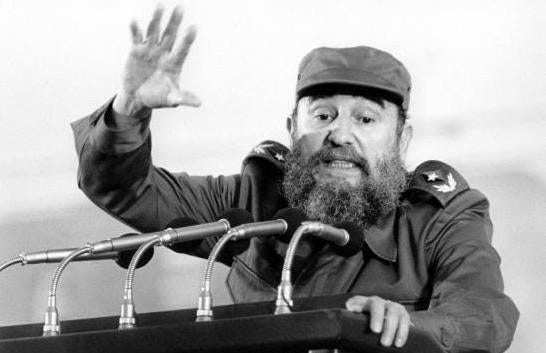

On This Day 1953: Fidel Castro’s Failed Moncada Barracks Raid Ignites the Cuban Revolution

The botched assault of 26 July 1953 ended in bloodshed, but it sparked a movement that would topple a regime and reshape Cuba’s future.

History rarely announces itself with a flourish. Often, it sneaks in through the back door, dishevelled and uncertain, wrapped not in glory but in failure. And so it was on the 26th of July, 1953, in Santiago de Cuba, when a young lawyer by the name of Fidel Castro launched a botched assault on the Moncada Barracks, setting in motion a revolution that would come to define a nation for decades.

There were no grand declarations of triumph that morning. What began as a strike against military dictatorship ended in bloodshed, chaos and swift retaliation. Yet from this defeat rose a movement that would eventually sweep aside the old order, enthroning Castro and his ideals as the new force in Cuban life.

This was the moment the Cuban Revolution truly began, though few would have recognised it at the time.

A Cuba on the Brink

In the early 1950s, Cuba was simmering with discontent. Fulgencio Batista, once a revolutionary himself, had seized power in a military coup in 1952, suspending the constitution and installing himself as a strongman ruler. Corruption ran rampant, wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few and the influence of the United States loomed large over Havana’s politics and economy.

For the poor and working class, daily life offered little hope. Among them, a 26-year-old Fidel Castro, a trained lawyer from a wealthy background, stood increasingly aghast at what his country had become. Educated, articulate and driven, Castro believed that the Batista regime could not be voted out through a compromised system. If democracy had failed, then the solution had to be revolution.

The Plan and the Raid

With this resolve, Castro assembled a small group of revolutionaries under the banner of a secret movement. Many were young, idealistic and untrained, but united by a shared belief that change had to come. Their target was the Moncada Barracks in Santiago, Cuba’s second-largest military garrison.

Castro’s plan was simple in theory but flawed in execution. He intended to seize weapons from the barracks, spark a popular uprising, and ignite a national rebellion. On the morning of 26 July, timed to coincide with the carnival in Santiago to avoid suspicion, the rebels struck.

Around 160 men and women were involved, divided into several assault teams. Fidel and his brother Raúl led the largest of the groups. Dressed in army uniforms and riding in stolen cars, they approached the Moncada Barracks before dawn. But almost immediately, the plan began to unravel.

The group was discovered prematurely, communication broke down and chaos ensued. The defenders of the barracks, far more numerous and better armed, responded with heavy gunfire. The element of surprise was lost, and within hours, the rebellion had been crushed.

In total, dozens of rebels were killed or captured. Many of those taken alive were subjected to torture and summary execution by Batista’s forces. Fidel and Raúl fled into the countryside but were arrested within days.

It had all the appearance of a complete failure.

Trial, Prison and the Making of a Revolutionary

What followed, however, was perhaps more powerful than any military success. Fidel Castro stood trial for his role in the assault and used the courtroom as his platform. Refusing legal representation, he famously defended himself with a rousing speech that would later be published under the title “History Will Absolve Me.”

It was in that courtroom that Castro truly became a national figure. His words were bold, defiant and filled with the promise of a better Cuba. He laid out the social and economic reforms he would enact if given power, including land redistribution, education reform and the return of democracy.

He was sentenced to 15 years in prison but served only 22 months before being released in a general amnesty in 1955, under mounting pressure from civil society. He left prison with more support than ever.

It was during this time that the movement born from the failed raid was named. Castro and his supporters began referring to themselves as El Movimiento 26 de Julio – the 26th of July Movement – in honour of the ill-fated attack that had begun their struggle.

The Revolution Begins in Earnest

Following his release, Castro left for Mexico, where he regrouped, trained and planned the next phase of the revolution. It was here that he met an Argentine doctor by the name of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who would become a vital figure in the revolutionary cause.

In December 1956, Fidel, Raúl, Che and 79 others sailed back to Cuba on the yacht Granma. What followed was a slow-burning guerrilla war waged from the Sierra Maestra mountains. Over two years, Castro’s forces grew in number and support, while Batista’s grip on power steadily weakened.

By January 1959, Batista fled the country. Fidel Castro marched triumphantly into Havana. The revolution, once thought extinguished in the fields outside Santiago, had succeeded.

Legacy of the 26th of July

The Moncada Barracks raid failed in its immediate objective but succeeded in something far more significant. It lit a fire that refused to go out. It turned a relatively unknown lawyer into a revolutionary icon. It gave Cuba a myth, a martyrdom and a movement.

To this day, 26 July remains a national holiday in Cuba – Día de la Rebeldía Nacional – the Day of the National Rebellion. The barracks themselves have been converted into a school and a museum, their bullet-ridden walls preserved as a reminder of what was started there.

For supporters of the revolution, Moncada symbolises sacrifice and the beginning of liberation. For critics, it marks the start of decades of authoritarian rule under Castro’s regime. But whatever one’s view of Fidel or of Cuba’s path since, the events of that Sunday morning in 1953 remain pivotal.

History, as it so often does, turned on a moment of apparent defeat.

A Revolution in Retrospect

Looking back from the safety of hindsight, it is tempting to see inevitability where there was once only uncertainty. The attack on the Moncada Barracks could easily have been another forgotten failure, buried in the dust of history. But the mythologising power of revolution thrives on sacrifice, and that failed raid gave Cuba its symbol.

It gave its revolution a date, a name and a cause. It gave Fidel Castro the platform he needed to become something more than a man. It gave the world yet another example of how deeply history can be shaped not by success but by resilience in the face of failure.

And that, in the end, might be the greatest lesson of 26 July.