On This Day 1947: Dior Unveils the New Look and Changes Fashion Forever

How one February afternoon in Paris restored glamour, confidence and a new vision of femininity

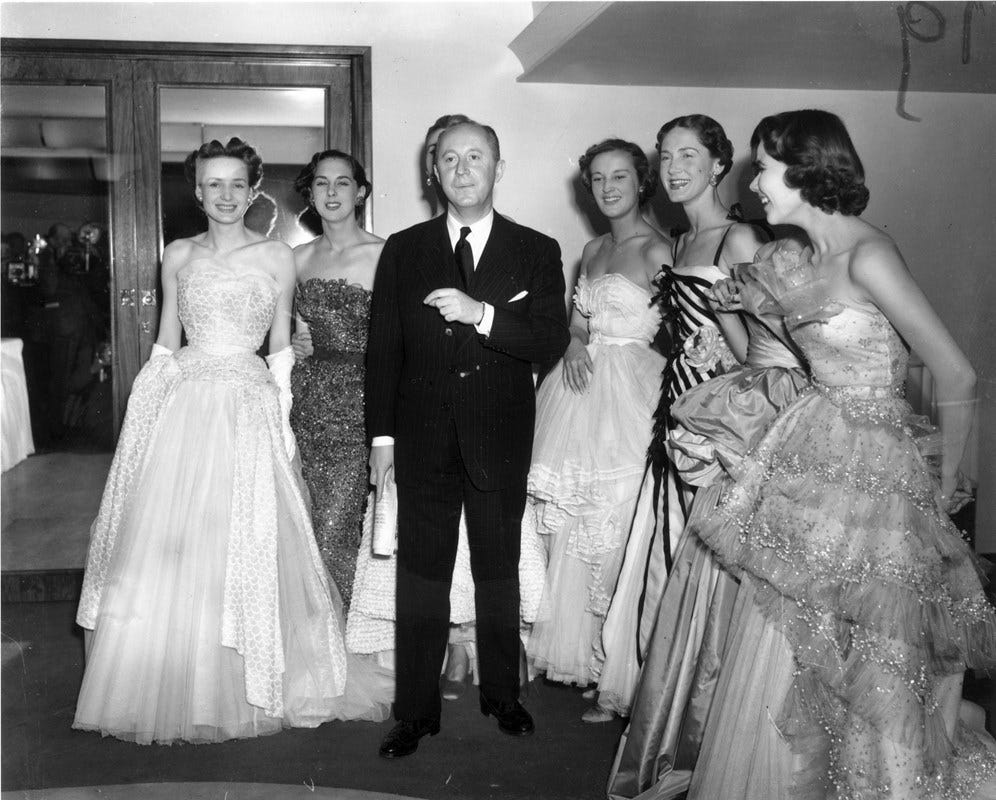

On This Day, 12 February 1947, inside a modest salon at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris, a 42-year-old designer stepped forward to present his first collection. Within hours, fashion history had turned a corner. The name above the door was Christian Dior, and the collection would soon be known around the world as the New Look.

It is easy, with hindsight, to see the New Look as inevitable. It was nothing of the sort. It was a gamble made in a city still scarred by occupation, in a country rationed and weary, in a Europe unsure how to feel beautiful again.

What happened that day was more than a fashion show. It was a declaration that hardship would not have the final word.

War Years and the Age of Austerity

To understand why the New Look struck with such force, we must return to the years that shaped it. During the Second World War, cloth was controlled as tightly as fuel. Silk vanished into parachutes. Metal fastenings were redirected to the front. Hems narrowed. Pleats were trimmed away. Decoration became suspect. Practicality ruled.

Women adapted with stoicism. Trousers, once rare in polite society, became common. Jackets were square shouldered, skirts short and economical. Fabric was saved wherever possible. Fashion houses in Paris struggled under occupation. Some closed their doors. Others survived under uneasy compromise.

The silhouette of the era told its own story. Hard lines, reduced shapes, no excess. A reflection of the mood. A continent at war does not dress for flourish.

When peace returned in 1945, relief did not immediately translate into indulgence. Rationing continued. Cities were rebuilding. Families were counting losses. The idea of extravagant fashion seemed, to some, almost indecent.

Yet beneath that caution was something else. A hunger. Not simply for clothes, but for renewal.

February 1947 and the Birth of a Silhouette

On 12 February 1947, Dior presented two lines that would come to define his early vision, En Huit and Corolle. The shapes were unmistakable. Rounded shoulders. A fitted bodice. A waist drawn in to startling narrowness. Skirts that swept outward in generous folds, using metres of fabric that would have been unthinkable only a year earlier.

One outfit in particular, later known as the Bar suit, captured the essence of the moment. Its cream jacket curved softly over the hips before cinching tightly at the waist, paired with a full black skirt. The effect was floral, almost architectural. Structured yet romantic.

Dior had trained his eye in art before fashion. He understood line, balance and drama. He also understood timing. He sensed that women no longer wished to resemble soldiers or factory workers. They wanted to feel like women again, in whatever way that word meant to them.

In his own reflections, he described his intention as a reaction against the poverty of imagination that had defined the war years. He designed, as he put it, for flower like women.

That phrase matters. Dior was not merely cutting cloth. He was offering a mood.

Why the New Look Was Revolutionary

The revolution lay in three bold decisions.

First, fabric. At a time when materials were still scarce, Dior used them lavishly. A single skirt might require twenty yards. To critics, this was wasteful. To supporters, it was liberating. Abundance replaced restraint.

Second, structure. Although he rejected the rigid corsetry of earlier decades, Dior shaped the body through meticulous tailoring, internal supports and careful construction. The waist was emphasised. The hips were padded. The silhouette was sculpted.

Third, psychology. This is where the true impact sits. After years of uniforms and utility, women were presented with something unapologetically elegant. It suggested that hardship could be followed by grace.

The reaction was immediate and intense. Some women embraced the style with delight. Others protested. In certain cities, those wearing full skirts were heckled for extravagance. There were reports of garments being tugged and torn by demonstrators who felt that such luxury mocked continued austerity.

Yet fashion magazines seized upon the look. Editors declared it new. The name stuck. Buyers placed orders. From Paris the style travelled to London, New York and beyond. Within months, copies and adaptations appeared in department stores across continents.

The New Look did not whisper its arrival. It commanded attention.

Personal Struggle Behind the Glamour

It is tempting to view Dior’s success as smooth and preordained. It was not. Before fashion, he had dealt in art, backing daring works such as Salvador Dalí’s surreal canvases when they puzzled many viewers. Economic collapse forced him to close his gallery. Illness nearly ended his career before it began.

The war years struck closer still. His sister Catherine joined the French Resistance, was arrested, and deported to a concentration camp. Her survival was uncertain until liberation. That experience left its mark.

When Dior later created his first perfume, he named it Miss Dior in her honour. It was not a marketing flourish. It was personal. The fragrance, like the clothes, carried a message of rebirth.

In that sense, the New Look was not simply commercial strategy. It was shaped by loss, resilience and a belief that beauty has a place even after brutality.

Legacy in Modern Fashion

Nearly eight decades on, the influence of that February afternoon remains visible. Designers at the House of Dior have revisited the silhouette repeatedly, each interpreting it for a new generation.

Raf Simons, in his debut couture collection for the house in 2013, reworked the hourglass shape with a lighter touch, softening the structure while retaining its essence. Maria Grazia Chiuri has continued to revisit the cinched waist and full skirt, adjusting proportion and purpose to reflect contemporary values and freedoms.

The New Look endures not because fashion stands still, but because it adapts. The hourglass has been tightened, loosened, sharpened and relaxed, yet its core idea persists. Shape as statement. Elegance as assertion.

Today, when discussions of fashion often centre on identity and autonomy, the New Look prompts debate. Was it a return to restrictive femininity or a celebration of it. My view is clear. In 1947 it represented choice. After years in which clothing was dictated by war, women were offered something expressive and unapologetic.

That matters.

On This Day and What It Still Means

On This Day in 1947, applause echoed in a Paris salon as a nervous designer pressed his hands to his ears, overwhelmed by the response. He could not have known that he had altered the direction of post war style.

The New Look signalled that the world was ready, or at least willing, to imagine something brighter. It challenged austerity not with slogans but with seams and silk. It restored Paris to the centre of fashion. It reshaped the female silhouette for a generation.

More than that, it captured a fragile but growing optimism. In the wake of devastation, people sought signs that life could expand again. Dior offered expansion in cloth, in line, in spirit.

Fashion often reflects its age. In 1947, it did more. It helped define it.

When we look back at that February afternoon, we see dresses and jackets. We should also see courage. To spend lavishly when caution ruled. To emphasise beauty when memories were raw. To suggest that femininity could be soft yet strong.

That is why the New Look was revolutionary. Not because it introduced a new hemline, but because it shifted the emotional weather of its time.

And that is why, on this day each year, it deserves to be remembered.