On This Day 1944: Why Stalin Let His Greatest Spy Hang

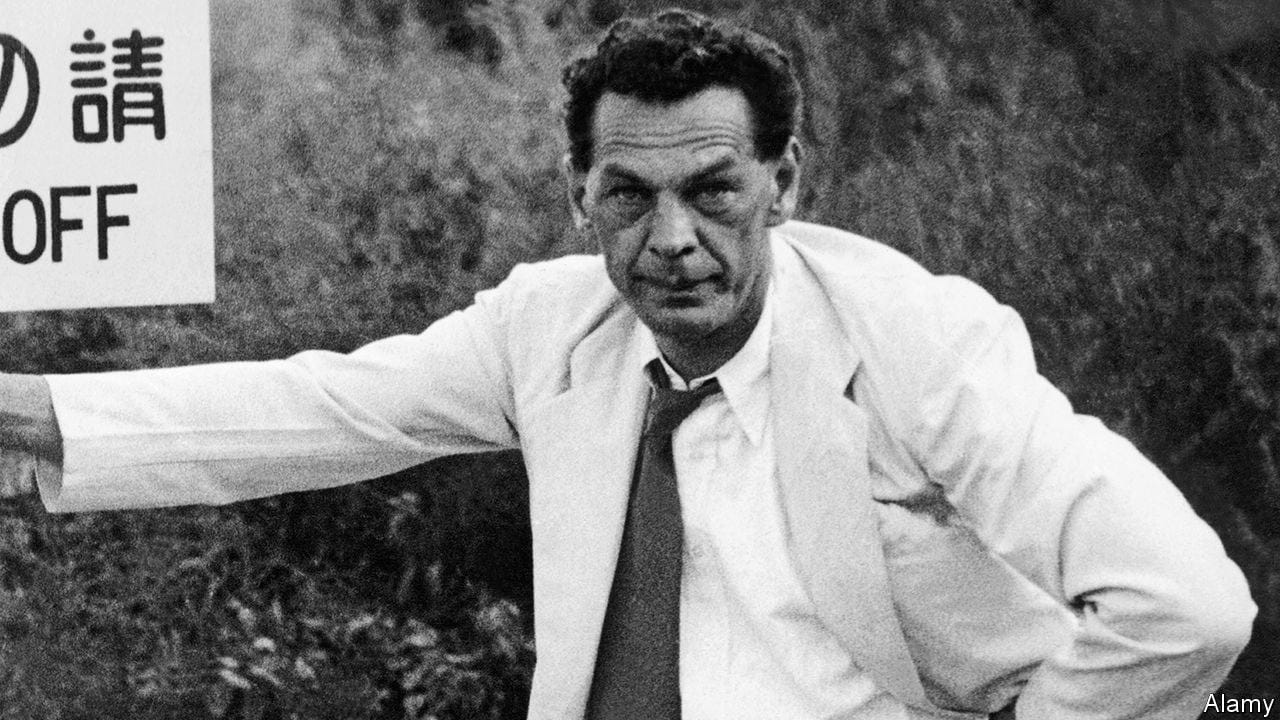

Richard Sorge risked everything to protect the Soviet Union. When the time came, Stalin left him to die.

History Doesn’t Lie, But Leaders Often Do

On 7 November 1944, at 10:20 in the morning, Richard Sorge was led to the gallows in Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison. His ankles were tied, a black hood pulled over his head. He declared his loyalty to the Red Army and the Communist Party with his last words. Then the trapdoor opened and the rope snapped his neck.

This was not some amateur caught in the wrong place. Sorge had been Stalin’s most valuable spy, a man who infiltrated the Nazi Party, embedded himself inside the German Embassy in Japan, and provided Moscow with intelligence that could have changed the course of the Second World War. He warned of Hitler’s plan to invade the Soviet Union. He reported Japan’s intentions to strike Pearl Harbor. Yet none of it mattered in the end.

Joseph Stalin let him hang and pretended he had never existed.

From Battlefield Blood to Marxist Belief

Sorge’s journey into espionage did not begin with ideology. It began with blood.

In 1917, as a young German soldier in the trenches of Minsk, he was blown out of his position by a Russian shell. He lost fingers, damaged his legs, and was pulled from the front to recover. It was in hospital that a communist doctor got to him, not with politics but with purpose. Sorge, angry, broken, and disillusioned, found meaning in the socialist cause. By the time he returned to civilian life, he was a true believer.

He studied philosophy and economics in Berlin, mixing academics with activism. He joined the Communist Party and began writing sympathetic articles for leftist publications. But it was not the writing that made him useful. It was the access. He knew how to blend in, how to listen, how to ask the right questions without seeming suspicious. Soviet intelligence spotted the potential immediately.

He accepted their offer and left for Moscow.

What followed was not the glamorous world of spy fiction. It was patience, danger, and performance. In London, he was deported. In Germany, he played the Nazi sympathiser. In China, he infiltrated nationalist circles. Each time, he walked closer to the edge, and each time, he delivered.

But Tokyo would be his final assignment, and it would cost him everything.

The Spy Who Saw What Stalin Refused To

By 1938, Sorge was posing as a Nazi journalist in Japan. He joined the German Embassy’s social circles, drank heavily, and cultivated contacts with both Germans and Japanese. He recruited fellow reporters with leftist leanings, seduced the wife of a military attaché, and quietly built a network of Soviet agents.

He learned what mattered. Germany and Japan were drawing closer. Japan had no plans to attack the Soviet Union but was instead preparing for war in the Pacific. He warned Moscow, stating clearly that the eastern Soviet border was safe. Stalin listened, then acted. He shifted troops west to face the Nazi threat. That move helped stop Hitler’s forces at the gates of Moscow.

Sorge had saved his country.

But when he warned that Germany was planning a full-scale invasion of the USSR, Stalin dismissed it. When Sorge discovered that Japan was preparing to strike the United States and Britain, Stalin ignored that too. Moscow received his intelligence, judged it too incredible, and failed to alert the Allies. Pearl Harbor was attacked weeks later.

By then, Japanese counterintelligence had taken notice. Sorge had been under pressure for years, drinking more, taking risks. After crashing his motorbike while drunk and being hospitalised, his briefcase went missing. A fellow Soviet agent recovered it, but the panic had started. Japanese police closed in.

On 18 October 1941, they raided his home and arrested him. He would never be free again.

Loyalty Betrayed in Silence

Sorge knew what he faced. Torture, interrogation, isolation. He endured all of it for three years. Under pressure, he confessed, but only after extracting a promise that his fellow agents’ families would be spared. That was the kind of man he was. Ruthless, brilliant, committed, and human.

The Japanese sentenced him to death, but hesitated. They were not at war with the Soviet Union and feared the political fallout of executing Soviet spies. They offered a prisoner exchange. Stalin could have saved him with a single word.

Instead, he denied Sorge’s existence. He ordered Soviet diplomats to claim the spy was a lunatic and that the entire case was fiction. Sorge, after more than a decade of serving Moscow, was left to die in silence.

He was hanged on 7 November 1944. The Soviet Union did not acknowledge him until twenty years later. By then, it was too late for anything except propaganda.

What Sorge Proved, And What Stalin Feared

Sorge’s life exposed something Stalin never wanted to admit. That the survival of the Soviet state had often depended on people who thought for themselves, who acted on truth even when the leadership ignored it. Sorge was not a yes-man. He was a realist. He gave Stalin accurate intelligence, not the reports the Kremlin wanted to hear. That made him dangerous.

He had outlived his usefulness the moment he made Stalin uncomfortable.

His story is not just about espionage. It is about loyalty betrayed. About a man who gave everything to a cause and was abandoned when it no longer suited the political narrative. The Soviets had a chance to honour his work while he was alive, to protect a man who had saved them more than once. Instead, they watched him hang and buried the truth until it was politically convenient.