On This Day 1920: The 19th Amendment and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage

From the brutality of the Night of Terror to the decisive vote in Tennessee, the long fight for women’s suffrage reached victory on this day.

From Prison Cells to the Ballot Box

It was on 18th August 1920 that the United States finally enshrined in law what countless women had fought for across decades, the right to vote. The ratification of the 19th Amendment marked the culmination of a bitter struggle, one that had seen women arrested, humiliated, and beaten, yet never silenced. To understand the scale of this achievement, it is worth looking back at the moments of brutality that forced a nation to confront its own hypocrisy about democracy.

The story begins in places like the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia, where women were dragged for daring to demand a voice. Nights of cold drizzle, iron bars, and hostile wardens like Superintendent Whitaker formed the backdrop to one of the darkest chapters of the suffrage movement. Yet it was those hardships that transformed a campaign into a national reckoning.

The Road to the Workhouse

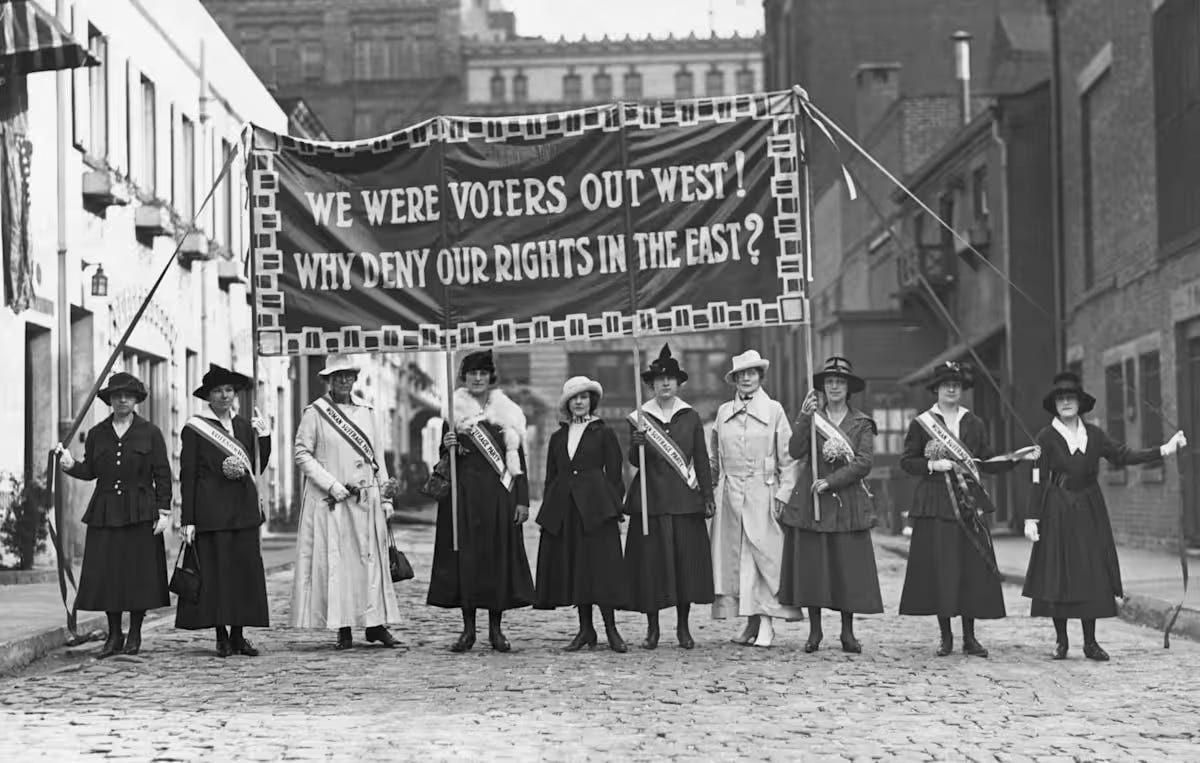

By the time the United States entered the First World War, suffragists had already been campaigning for decades. The movement was divided at times between those who preferred patience and persuasion and others who believed in public protest and confrontation. Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party embodied the latter. They staged parades, marches, and the famous Silent Sentinels pickets outside the White House, holding banners that directly challenged President Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric of democracy abroad while denying it at home.

For many Americans, these protests were uncomfortable. Women were supposed to be modest and obedient, not chaining themselves to railings or confronting power head-on. The government reacted by ordering arrests. Charges were often flimsy, from blocking traffic to causing public disturbances. The truth was that women were being punished not for disorder, but for daring to demand equality.

The Night of Terror

That brings us back to Occoquan Workhouse. On 14th November 1917, more than thirty suffragists were transferred there, including figures such as Lucy Burns. What followed became known as the Night of Terror. Guards beat women, twisted their arms, chained them to cell bars, and left them bleeding. Lucy Burns was handcuffed with her arms above her head and left dangling all night. Others were thrown against walls or denied food and medical attention.

The cruelty of that night shocked even those who had been sceptical of the suffrage cause. News spread rapidly, helped by sympathetic lawyers and journalists who risked reprisals to publicise what had happened. Suddenly the question was no longer whether women deserved the vote, but how long America could tolerate the spectacle of its government brutalising peaceful protesters.

Public Opinion Turns

The tide began to shift. President Wilson, who had long hesitated, was forced to acknowledge that women’s suffrage was a matter of justice. The United States, he argued in early 1918, could not claim to fight for democracy in Europe while denying it to half its population at home.

Yet even with presidential support, the road to constitutional change was not simple. The amendment had been proposed in Congress multiple times since 1878 but always fell short. It took the political momentum of wartime, combined with the outrage from Occoquan and other arrests, to finally push it forward.

The Crucial Vote of 18th August 1920

The text of the 19th Amendment was simple but profound: The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

By 1920, 35 states had ratified the amendment, just one short of the three-fourths needed. The battleground was Tennessee. On 18th August, after fierce debate and heavy lobbying from both suffragists and anti-suffragists, the Tennessee legislature voted. It came down to one man, Harry T. Burn, a 24-year-old representative who had initially opposed the amendment.

Burn carried in his pocket a note from his mother urging him to “be a good boy” and vote for suffrage. He did so, breaking the deadlock and securing the 36th ratification. With that, the 19th Amendment was passed into law.

A Hard-Won Victory

The ratification of the 19th Amendment was not the end of the story. For many women, particularly African American, Native American, and immigrant women, barriers remained in place through discriminatory state laws, poll taxes, and literacy tests. It would take the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s to dismantle many of these obstacles.

Nonetheless, 18th August 1920 stands as a milestone. It represents the moment when decades of struggle, sacrifice, and suffering finally bore fruit. The women who endured prison, hunger strikes, and the Night of Terror did not do so in vain. Their determination forced a nation to live up to its democratic ideals.

Why 18th August Still Matters

Looking back from today, 18th August is not just a date on a calendar. It is a reminder that rights are never simply handed down, they are fought for. The suffragists understood that democracy is meaningless if it excludes half the population.

It is also a lesson in persistence. For more than forty years, campaigners introduced the same amendment in Congress, facing defeat time and again. They endured ridicule, violence, and imprisonment. Yet they never abandoned their goal. The victory in 1920 was not sudden, it was the slow accumulation of countless acts of courage.

Finally, 18th August warns us about complacency. The struggles of the suffragists remind us that rights once won must also be defended. Equality is not a static achievement, it is an ongoing responsibility.

Conclusion

The image of rain-soaked police vans pulling up to the Occoquan gates in 1917 speaks to the price that was paid for democracy. The bruises and broken spirits of those nights were transformed into a movement that reshaped the American political landscape.

On 18th August 1920, the United States changed forever. Women walked into polling stations across the nation in the years that followed, not as trespassers in a male domain but as equal citizens. The long march from the prison yard to the ballot box was complete.

History remembers battles and wars, but it must also remember the silent vigils, the hunger strikes, and the nights of terror endured by women whose only crime was wanting their voice heard. Their courage gave meaning to the word democracy.