On This Day 1920: Birth of the Negro National League and a Defiant Stand for Black Baseball

How Rube Foster Turned Fury into a Movement That Changed the Game

On this day in 1920, in a modest meeting room in Kansas City, a group of Black baseball men chose self determination over pleading for acceptance. What they founded, the Negro National League, was more than a sporting competition. It was an act of organised defiance in an America that had drawn its colour line in thick ink.

To understand why that moment matters, we must begin in Chicago, where injustice was not an abstraction but a daily fact.

Racial Tension and Resolve in Chicago

In the long, hot summer of 1919, Chicago simmered. When a Black teenager, Eugene Williams, drifted across an invisible racial boundary while swimming in Lake Michigan and was stoned by a white man, his death ignited days of violence. The city burned with grievance that had been building for years. Dozens died. Many more were injured. Trust between communities, already fragile, splintered further.

For Black Chicagoans, the lesson was plain. Protection would not come from polite appeals. Progress would not arrive by invitation. Institutions would have to be built, owned and defended from within.

Baseball, the national pastime, had barred Black players for decades. The so called colour line was unofficial yet rigid. Talented Black athletes were shut out of the major leagues and left to organise their own teams, often with meagre backing and uncertain schedules. They played exhibitions against white clubs when permitted, endured poor facilities, and relied on gate money that could vanish with one rainstorm or one cancelled fixture.

It was a precarious existence. It was also intolerable.

Rube Foster’s Vision for Black Baseball

At the centre of the push for change stood Rube Foster, a formidable pitcher turned organiser. Foster possessed a fast mind and a faster temper. He had tasted success on the mound and understood the game’s subtleties, yet he also recognised the structural trap. As long as Black teams depended on white promoters, white ballparks and white goodwill, they would remain vulnerable.

Foster had already demonstrated what ambition and organisation could achieve. With the Chicago American Giants, he secured better grounds, attracted elite players and built a following that filled the stands. His team won consistently and carried itself with professional pride. That success sharpened his thinking. If one well run club could thrive, why not a league built on similar principles?

The idea was simple, though not modest. Create a stable, self governing circuit of Black owned teams. Agree schedules in advance. Crown a champion on merit. Share gate receipts in a structured way. Replace chaos with order.

On 13 February 1920, eight Midwestern club owners met and agreed to form the Negro National League. Foster was elected president. It was a bold declaration that Black baseball would no longer live on scraps from another table.

Early Success and Growing Pains

The league’s first season proved that the concept could work. For the first time, a Black professional baseball league completed a full campaign without collapsing. Crowds turned out in strong numbers. Newspapers within the Black community followed results keenly. The players, denied entry to the established major leagues, now had a platform worthy of their talent.

Yet human frailty travels with any institution. Foster’s competitive instinct did not subside when he became league president. Rivals accused him of favouring his own Chicago club in scheduling and player recruitment. Complaints surfaced that the American Giants enjoyed a surplus of home games and advantageous fixtures. Whether exaggerated or justified, the perception of imbalance strained relationships.

Still, the broader achievement stood firm. The Negro National League created a commercial and cultural ecosystem in which Black athletes could excel before Black audiences. Teams such as the Kansas City Monarchs emerged as formidable forces, winning titles and cultivating stars who would later command national attention.

The league’s existence also inspired parallel ventures in other regions. Black baseball was no longer an afterthought. It was an enterprise.

Legacy That Shaped Major League Baseball

The league did not endure unchanged. Economic pressures intensified with the onset of the Great Depression. Gate receipts dwindled. Owners struggled. By 1931, the original Negro National League folded under financial strain. Yet its blueprint survived. A reconstituted version would follow, and inter league championships known as the Negro World Series would captivate supporters.

More importantly, the standard of play within the Negro leagues was undeniable. Scouts from white major league clubs could not ignore the quality forever. In 1947, Jackie Robinson stepped onto the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the colour barrier that had excluded Black players for more than half a century. He was soon joined by others, among them Satchel Paige and Larry Doby, whose reputations had been forged in the Negro leagues.

Young talents such as Willie Mays began their journeys in Black baseball before ascending to the integrated major leagues and, in Mays’s case, to immortality.

Integration marked progress, yet it also hastened the decline of the Negro leagues. As top players departed for the majors, attendance fell. By the mid twentieth century, the Black only leagues that had once symbolised autonomy and resilience faded from the scene.

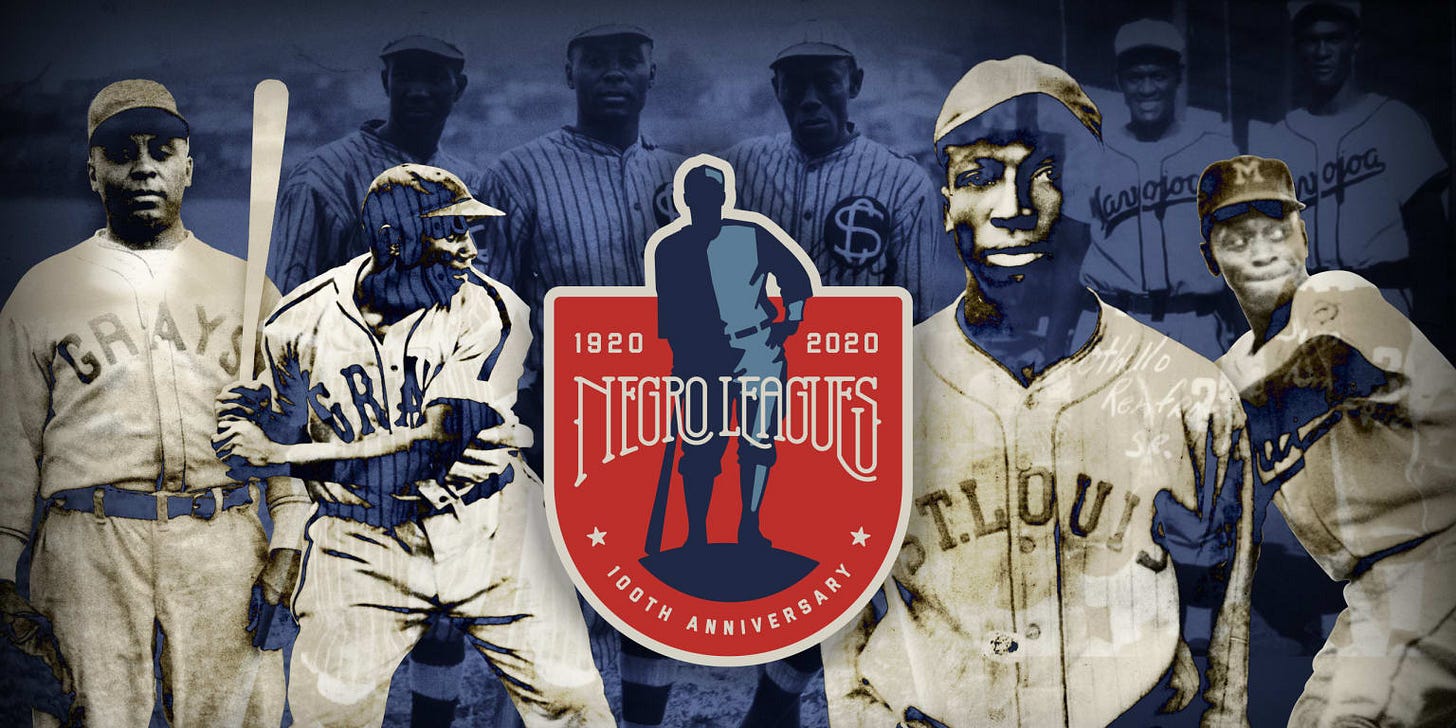

In 2020, Major League Baseball formally recognised several Negro leagues, including the original Negro National League, as major leagues. Statistics were incorporated into the official record. The gesture, long overdue, acknowledged what many had always known. The quality of competition had been first rate. The exclusion had been political, not athletic.

For me, that recognition matters, though it cannot fully redress the imbalance. Records are important. So is memory. On this day in 1920, the founders of the Negro National League were not asking for validation. They were asserting it.

Enduring Significance of 13 February 1920

When we revisit 13 February 1920, we should resist the temptation to see it as a footnote on the road to integration. It deserves attention in its own right. The formation of the Negro National League was a declaration that Black enterprise could match any standard when given structure and belief.

It was born from anger, yes, but also from clarity. If doors remain closed, build your own house. Foster and his fellow owners did precisely that. They created schedules, championships and careers. They offered young players a horizon that extended beyond sandlots and segregated exhibitions.

The league’s story contains contradictions. Its president could be high handed. Rivalries flared. Finances wobbled. Yet those imperfections render it human rather than mythic. Progress rarely arrives in tidy form.

Baseball likes to speak of timeless summers and pastoral calm. The truth, especially in early twentieth century America, was more turbulent. Diamonds were carved out of divided cities. Cheers rose from grandstands where pride and protest mingled.

On This Day in 1920, Black baseball stepped into organised self rule. It did so in the shadow of racial violence and in the face of institutional exclusion. That it flourished at all stands as testament to vision and resolve.

When modern fans examine the record books and see names once omitted now restored, they are glimpsing the afterglow of that February meeting. The Negro National League did not wait to be invited into history. It claimed its place.

And that, more than any box score, is why this date endures.