On This Day 1917: Caporetto, the Day Italy Came Undone

How one battle exposed the fault lines of an army and scarred a nation’s soul

The Battle of Caporetto - Valley of Ghosts

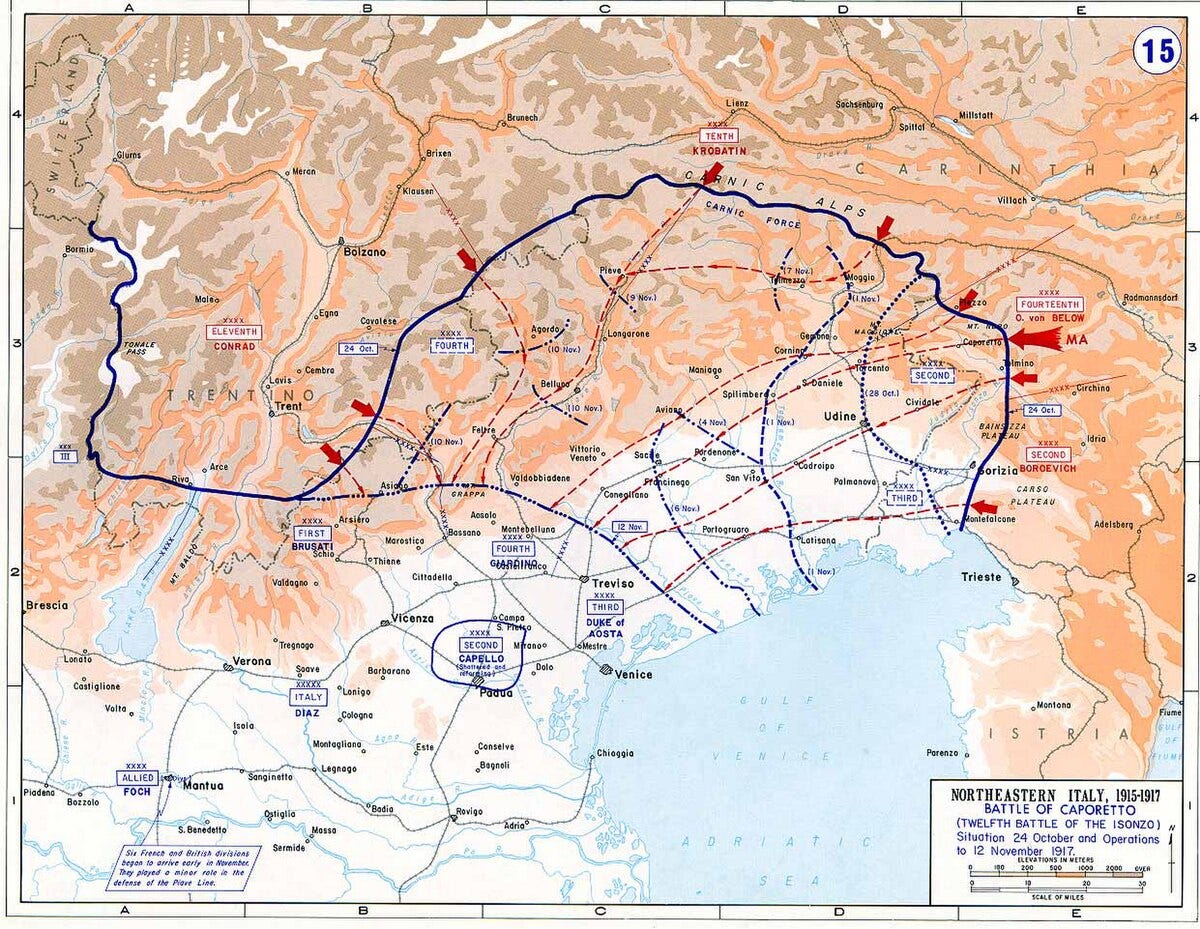

On this day, 24 October 1917, Italy suffered its most devastating military collapse at the Battle of Caporetto. What unfolded in the Alpine valleys near the Isonzo River was more than a defeat, it was a national unravelling. The Italian army, weakened by years of trench warfare and hollow leadership, was shattered by a meticulously planned and ruthlessly executed Austro-German offensive. Caporetto was not just a failure of arms, it was a failure of command, of morale and of identity.

It is tempting to pin the disaster on fog, bad luck or superior enemy tactics. But this was no fluke. Italy’s defeat was born long before the first artillery shell screamed through the morning air. It was forged in brittle alliances, overreaching ambitions and delusions of grandeur that defined Italy’s entry into the war. The cracks were always there. Caporetto simply forced the country to face them.

Italy’s Dream Was Always Fragile

Italy entered the First World War not out of loyalty, but out of calculation. In 1915, it was still neutral, playing diplomatic poker with both the Central Powers and the Entente. The Treaty of London sealed its decision. In exchange for joining the Allies, Italy was promised Austro-Hungarian territory, including Trento, Trieste and parts of the Dalmatian coast. These were lands Italy considered rightfully hers, inhabited by Italian speakers, wrapped in the rhetoric of national destiny.

But dreams of swift conquest evaporated quickly in the mud and blood of mountain warfare. The Italian front froze into a stalemate. Eleven battles along the Isonzo River yielded little more than body counts. Italian commanders sent men charging up vertical slopes into machine gun fire with the same blind persistence, convinced that patriotic willpower could break geography and logistics.

What they got instead was two years of attrition. Men starved, froze and died in trenches chiselled into stone. Discipline hardened into cruelty. Morale sank into bitterness. And when the storm finally came at Caporetto, the Italians were already exhausted, divided and exposed.

Caporetto Was Not a Battle, It Was a Collapse

At 2 a.m. on 24 October, German and Austro-Hungarian forces launched their assault under cover of fog. The opening artillery barrage used poison gas, catching the Italian lines off guard. Trenches fell silent. Units scattered. Communications vanished.

The Italian front did not bend, it broke. Commanders had no idea where their troops were. Divisions retreated without orders. Ammunition ran out. Chaos reigned. In some places, Italian soldiers surrendered in groups, unarmed and leaderless. Others simply walked away.

Within hours, entire regiments dissolved. A week later, Italy’s Second Army had ceased to exist as a fighting force. Half a million men were lost, dead, captured or deserting. The army fell back nearly 100 miles, abandoning towns, supply lines and strategic positions. No single engagement in the Great War caused such an abrupt and sweeping collapse of a major force.

But Caporetto was more than a battlefield rout. It was a mirror held up to a country unprepared for the scale and demands of modern warfare. An army built more on nationalist speeches than cohesive planning was torn apart by precision, coordination and overwhelming firepower.

What Failed Was Not Just Strategy, But Trust

The real wound of Caporetto was psychological. Soldiers felt betrayed. They had been promised heroism, but found only hunger and futility. And when they retreated, they were called cowards by the same generals who had abandoned them.

German leaflets rained down from the skies blaming Italian troops for their own retreat. The accusation that the Second Army had broken ranks, despite following orders to fall back, pushed many to desert. It became clear that those in charge would protect their reputations before their men.

This betrayal fuelled an unprecedented wave of desertions. More than 300,000 soldiers scattered into the countryside. Not in defeat, but in disillusionment. These were not cowards. They were men who had been led to the slaughter for two years, then blamed for surviving it.

Caporetto became a national trauma not only because of how many died, but because it shattered the illusion that Italy’s war effort had a moral centre. When command collapses, so does faith.

Aftermath and Reckoning

The consequences were immediate and seismic. Italy’s Prime Minister Paolo Boselli and Army Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna resigned within days. British and French reinforcements rushed in to prevent a total collapse of the front. The Allies established a Supreme War Council to prevent such disasters from happening again. Italy’s new leadership focused on restoring order, morale and dignity to its battered troops.

Caporetto forced a reckoning with the cost of hubris. The Italian military would recover, and a year later, it would earn redemption at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, contributing to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But that victory did not erase the scars.

Caporetto entered the national memory as a warning, a bitter lesson in the dangers of overpromising and underpreparing, of ignoring morale, of pretending that willpower alone wins wars.

Final Thoughts

On this day in 1917, Italy faced its darkest military hour. The defeat at Caporetto was not merely about losing ground, it was about losing faith. In the system, in leadership, in the war itself.

If history teaches anything, it is that collapse does not come from nowhere. It builds slowly, invisibly, under the surface. And when it breaks, it breaks completely.

Caporetto remains a powerful reminder that the greatest threats to any nation in war often come not from the enemy, but from within.