On This Day 1870: When the Vote Was Won and the Fight Was Far From Over

How the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment marked a moral turning point in American history

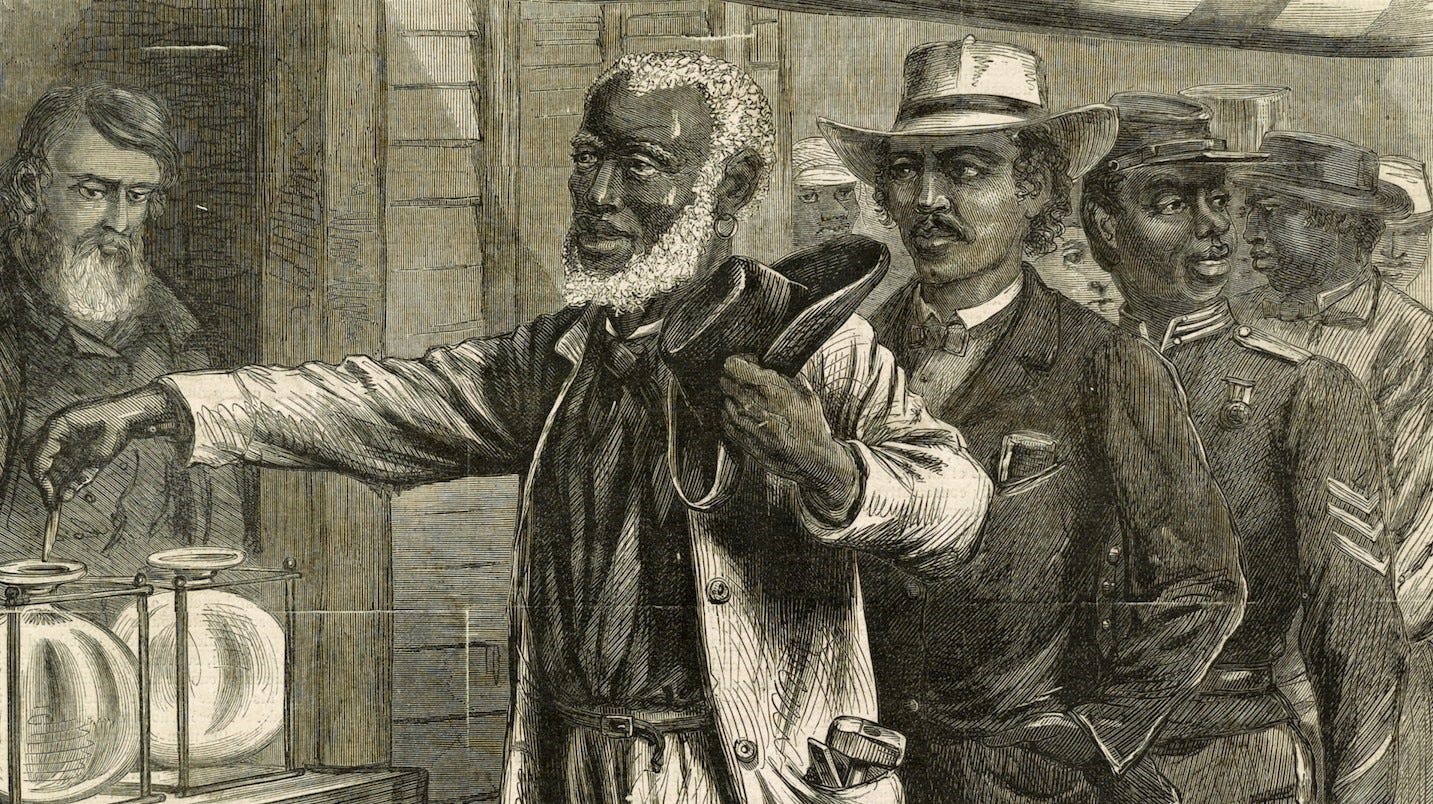

On this day in 1870, the United States ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. On paper, it was a triumph. The Constitution was altered to prevent states from denying the vote on the basis of race, colour, or previous condition of servitude. For the first time, Black men were formally recognised as political citizens of the republic they had helped to save.

Yet to understand why this moment still matters, and why it still troubles the conscience, we have to resist the temptation to treat it as a clean ending. It was not. It was a hard fought advance in a longer war, one waged not only against slavery, but against the deeper habit of racial power that survived it.

This was an amendment born of blood, argument, courage, compromise, and, ultimately, disappointment.

War service without citizenship

Seven years before ratification, a young Black soldier marched across a South Carolina beach towards a Confederate fortress. He wore the Union uniform, carried a rifle, and advanced under fire with hundreds of others like him. Many would not return. Nearly half would be killed or wounded.

They fought for a country that did not yet recognise their right to vote.

Black Americans had been barred from combat for most of the Civil War. When that barrier fell, their service was immediate and decisive. They proved their discipline, their bravery, and their commitment under conditions that tested even seasoned white regiments. The war could not have been won without them.

But when the guns fell silent, the contradiction remained. Men who had faced cannon and musket fire were expected to accept political silence. They could be taxed, drafted, and governed, but not represented.

That injustice did not fade with victory. It sharpened.

Slavery ended, power untouched

By 1865, slavery as a legal institution was finished. That fact tempted some to declare the work complete. The argument was neat, comforting, and wrong.

Ending slavery without securing political power left freed men exposed. Across the South, former Confederate elites reasserted control through law rather than chains. New statutes restricted movement, labour, and economic independence. These Black Codes differed in form from slavery, but not always in effect.

The federal government faced a choice. It could insist that freedom required enforcement, or it could retreat behind states’ rights and leave the matter to local authority. Too often, it chose the latter.

At the centre of the push for a different answer stood Frederick Douglass.

A voice that would not settle

Douglass had escaped slavery and remade himself as one of the most formidable moral voices of the nineteenth century. He understood, with absolute clarity, that freedom without the vote was conditional freedom.

His argument was simple and devastating. A people subject to the laws of a state must have a voice in shaping those laws. Anything less was a deception dressed up as progress.

He made that case everywhere, in churches, public halls, and directly to power. When he confronted Andrew Johnson at the White House, he met a president who believed Black suffrage would destabilise the nation. Johnson preferred to leave voting rights to the states, knowing full well how those states would act.

Douglass left that meeting knowing persuasion would not be enough. Power would have to be contested, publicly and relentlessly.

Elections, violence, and resolve

The election of 1868 exposed the stakes. In many former Confederate states, Black men were able to vote for the first time. Their participation proved decisive in the victory of Ulysses S. Grant, a man aligned with Reconstruction and federal protection of civil rights.

That participation came at a cost. Intimidation, terror, and organised violence were deployed to keep Black voters from the polls. The emergence of the Ku Klux Klan was not an aberration, it was a strategy.

Despite this, hundreds of thousands voted. They did so knowing the risks, because they understood the moment. Their ballots were acts of defiance.

Grant’s victory opened a narrow window. Congress moved to propose a constitutional amendment that would place voting rights beyond the reach of state governments. It was an imperfect instrument, but it was necessary.

Fractures within reform

Progress, however, rarely advances in a straight line. The push for the Fifteenth Amendment exposed painful divisions among reformers.

Douglass believed in universal suffrage. He wanted women to vote. He had worked alongside women’s rights activists for years. But he also believed in political timing. He feared that delaying the amendment would mean losing it altogether.

That conviction brought him into conflict with Susan B. Anthony, who opposed any amendment that enfranchised men while excluding women. Her stance was principled and understandable, but the disagreement cut deep.

It is tempting to judge one side or the other with hindsight. It is more honest to recognise the tragedy of reform movements forced to choose between partial justice now and fuller justice later.

The amendment moved forward without universal support.

On This Day, ratification at last

On this day, February 3, 1870, the required number of states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. The news arrived quietly, but its significance was immense.

The Constitution now stated that race could not be used to deny the vote.

For Douglass, it was a moment of vindication. Years of argument, travel, and personal strain had achieved their aim. The principle was established at the highest legal level.

Yet he was not naïve. He knew what law could promise, and what power could still take away.

Victory without enforcement

What followed confirmed his fears.

Without sustained federal enforcement, southern states found ways around the amendment. Literacy tests, poll taxes, intimidation, and outright fraud became tools of exclusion. The letter of the law remained, but its spirit was hollowed out.

Douglass would later describe this betrayal with bitter precision. Rights had been granted without protection. Citizenship declared without substance.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Black political participation in much of the South had been almost entirely erased. The Jim Crow system that followed did not contradict the amendment, it ignored it.

Why this day still matters

On This Day 1870 deserves remembrance not because it solved injustice, but because it defined it.

The Fifteenth Amendment established a truth that could not be unspoken. That political equality was not a gift, but a right. That service, sacrifice, and citizenship were inseparable. That democracy, if it meant anything, had to include those it governed.

Every later struggle for voting rights in the United States, from the civil rights movement of the twentieth century to debates in the present day, traces its legal and moral lineage back to this moment.

The amendment did not complete the journey. It marked the road.

History often tempts us with neat anniversaries and clean conclusions. This one resists that comfort. It reminds us that progress is rarely permanent, that rights must be defended as well as declared, and that the work of citizenship is never finished.

That is why February 3, 1870 still matters.