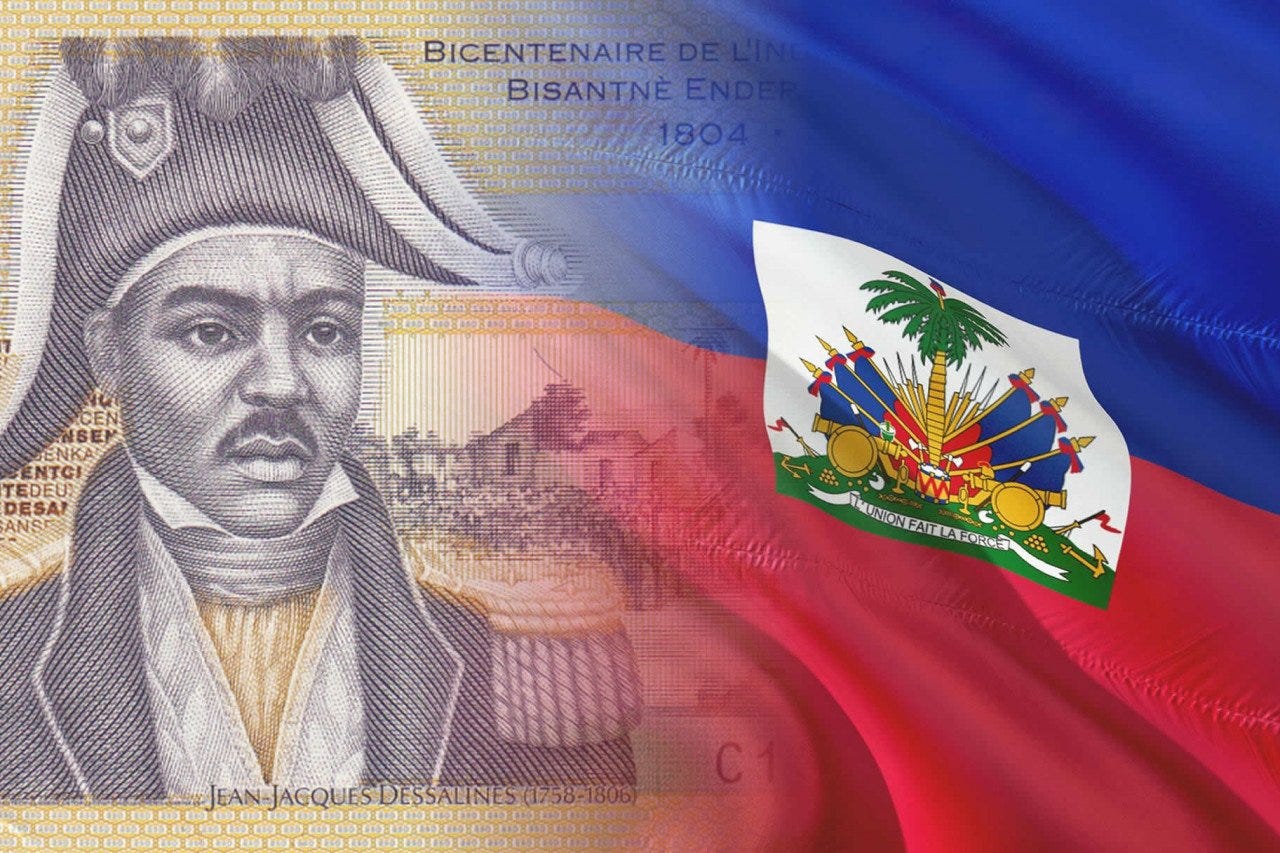

On This Day 1806, The Fall of Haiti’s First Emperor

Dessalines freed Haiti, then died by Haitian hands

Haiti’s Revolution Was Never Meant to End Like This

On 17 October 1806, Emperor Jacques I of Haiti, born Jean-Jacques Dessalines, was ambushed and killed by his own soldiers near Port-au-Prince. His bloodied body was dragged through the streets and dumped in the city square. Just two years earlier, he had stood tall as the father of Haiti’s independence, the general who had broken the French Empire in the Americas and formally abolished slavery. But by the time of his death, those closest to him had turned, seeing not a liberator, but a tyrant.

The story of Dessalines is not a simple one of heroism. It is a hard lesson in what can follow when revolutions win. The man who freed Haiti from colonial chains also ruled it with an iron grip. His life was defined by the brutality of empire, and his rule mirrored that brutality more than his followers were willing to accept.

Fire, Chains and the Fight to Break Them

Dessalines did not just lead a rebellion. He came from slavery. Every scar, every battlefield decision, was shaped by years in chains. He was not a man raised to speak of liberty in abstract terms. He knew its value in blood and in pain. When he stood on the walls of Fort Crête-à-Pierrot in March 1802, torch in hand, rallying men to resist the French siege, he was not preaching, he was surviving.

That fort did fall. But Dessalines did not. After a decade of brutal war, Haiti forced out Napoleon’s forces and declared itself a free nation on 1 January 1804. It became the first independent Black republic and the first post-slavery state in the Western Hemisphere. Dessalines, who had once served under Toussaint Louverture, now took the mantle of leadership as Governor General for Life.

But in the ashes of war, Dessalines made a choice that would shape his legacy. He did not build a republic. He built an empire, and crowned himself Emperor Jacques I.

From Liberator to Emperor

Haiti was free, but it was fragile. The world turned its back. The United States, afraid of a slave uprising within its own borders, banned trade with Haiti. France plotted revenge. The plantations lay in ruins, the economy collapsed, and Dessalines faced the impossible task of building a state from the ground up, surrounded by enemies and lacking allies.

His answer was control. He seized land, rebuilt state-run plantations, and imposed forced labour. Haitians who had fought for their freedom were ordered back into fields, working sugar and coffee farms under government command. It felt too much like the past. Dessalines insisted it was for survival, that Haiti could not stand without an economy. But to many, it looked like slavery by another name.

The violence did not end with the French. Dessalines ordered mass executions of white people suspected of supporting the French. He called it justice, the protection of revolution. But his grip on power tightened, and fear spread. Former comrades began to see him not as a saviour, but as the next tyrant.

The Betrayal That Was Coming

Dessalines did not fall to a foreign power. He was not taken by surprise. His assassination was the final move in a slow betrayal that had been building for months.

The conspirators included generals who had once stood beside him in the war for independence. Chief among them was Alexandre Pétion, a free Black man educated in France, a believer in the ideals of liberty and republicanism. He had seen revolution in Europe and could not accept Haiti’s slide into authoritarianism.

They waited until Dessalines was far from the capital, on one of his plantation tours. On 17 October 1806, near Port-au-Prince, soldiers blocked the road, muskets raised. Dessalines drew his pistol, refused to surrender, and fired. He was shot multiple times, pinned beneath his horse, bleeding out in a cane field.

His body was tied to a horse and dragged through the capital, dumped in public as a warning and a message. The revolution had eaten its own.

Dessalines Was Both

Today, Dessalines is rightly honoured as one of Haiti’s founding fathers. His military brilliance broke one of the world’s most powerful empires. His victory helped spark the end of slavery across the Americas. He did what no one else had done. He built a Black nation in a world that wanted it dead.

But he was also a man shaped by war, and by the slavery he had escaped. His rule became harsh, and the methods he used to defend the revolution made him feared by those who once followed him. The Haiti he left behind did not find peace. Civil war followed, and the nation’s political instability endured for generations.

To understand Dessalines, you must hold both truths. He was not simply a hero or a villain. He was the product of a system that crushed lives and punished dignity. He rose through it, defied it, and eventually mirrored it.

On this day in 1806, Haiti lost its first emperor. But the shadow of his rule remains long and complicated, just like the revolution he led.