On This Day 1789: The Quiet Birth Of A Nation’s Thanksgiving

How George Washington used gratitude to steady a fractured young republic

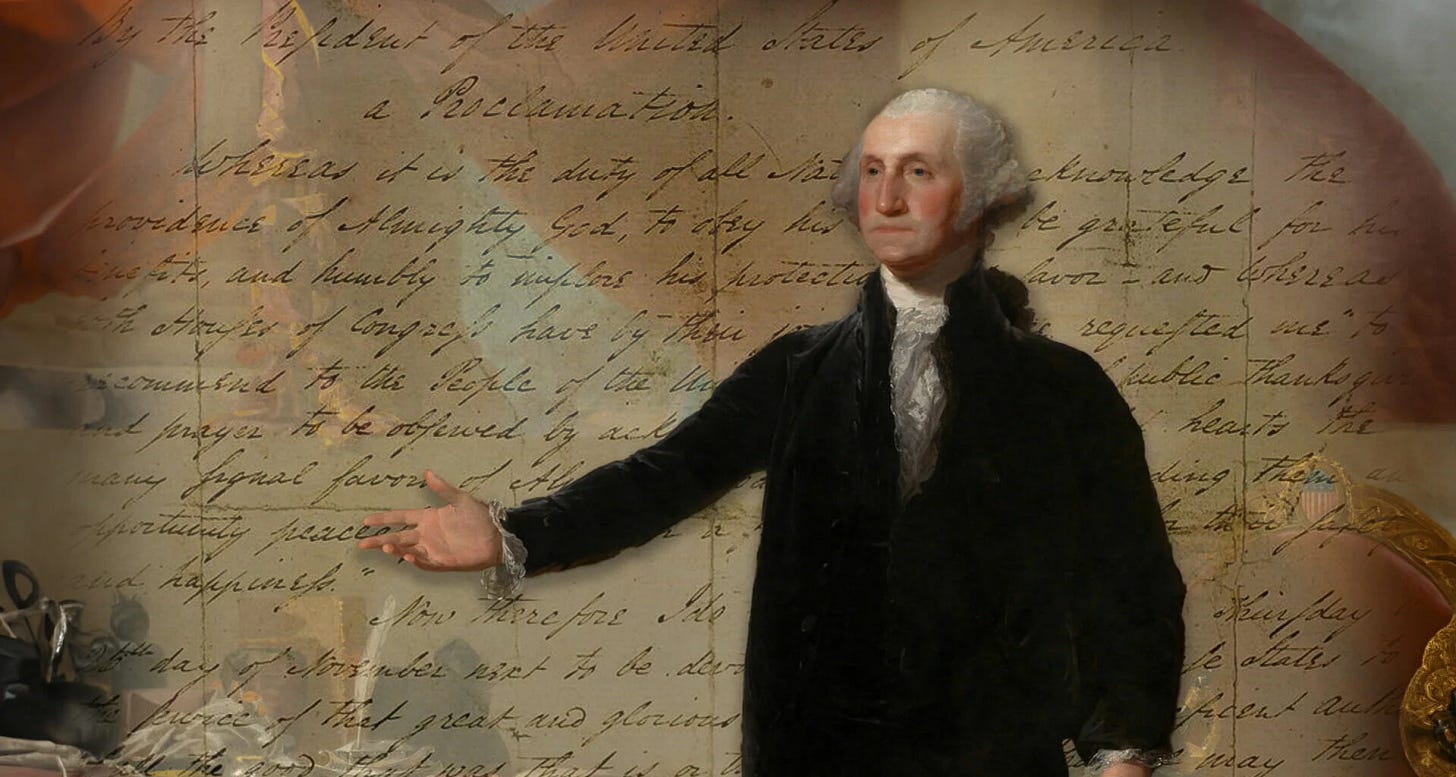

America in the late 1780s was a nation still learning how to breathe. The smoke of revolution had barely cleared when internal unrest arrived, testing the strength of a country that had not yet taken full shape. On this day in 1789, President George Washington issued the first national Thanksgiving proclamation, and although the weather drowned out his hopes for a unifying public celebration, the gesture itself carried far more weight than the turnout at St Paul’s Chapel.

As a history writer, I find myself returning often to these early years after independence because they reveal something that gets hidden behind the polished myths. These men, celebrated and criticised in equal measure, were improvising. They were unsure. They were frightened of the world they had made and the forces they could not control. Washington’s Thanksgiving carries that uncertainty deep within it, yet it also offers something rare, a moment when a leader tried to bind wounds not through power, but through shared reflection.

This is why I believe Washington’s first Thanksgiving still matters. Not because of turkey, parades or any of the modern trimmings, but because of what it represented: a president looking across a fractured landscape and deciding that unity, however fragile, was worth pursuing.

Shays’ Rebellion And The Price Of A New Republic

Before we can understand why Washington reached for the idea of a national day of thanks, we need to see the country he was inheriting. In January 1787, two years before his proclamation, gunfire cracked across a snowy field outside the Springfield Arsenal. Veterans of the revolution faced each other across the ice, some defending the state armoury, others following Daniel Shays’ protest against crushing debt and relentless taxation.

The moment is chilling to picture: men who had stood shoulder to shoulder against the British now raising weapons at former comrades. Shays’ followers were farmers pushed to breaking point. Their rebellion was not an organised revolution, but a cry for relief from a government that seemed distant and indifferent. General William Shepard’s warning shots skimmed over their heads, and still they advanced, convinced their country had betrayed them.

Four men died that day. Many more fell in the snow, wounded and stunned by the realisation that independence had not delivered security. Instead, it had exposed every weakness lurking beneath the surface. This event haunted Washington, even before he returned to public life. It pushed him back into the arena when he would rather have stayed at Mount Vernon. He understood the message: a nation could win a war and still lose its people.

The rebellion helped drive the creation of the Constitution, yet the document itself became another arena of conflict. Federalists demanded a strong centre, anti-federalists feared the rise of new tyranny. Washington stepped into the presidency with factions already sharpening their arguments, each convinced the other threatened the country’s future.

No wonder he approached the inauguration as if walking to the gallows.

Washington’s Journey And The People Who Lifted Him

Washington, heavy with doubt, riding north toward New York for his inauguration, sees a crowd on the road ahead. For a heartbeat he fears attack. Instead, he finds neighbours, farmers, townspeople, cheering not the idea of a president, but the man they believed could hold the country steady.

These scenes repeated themselves all along the route. Each gathering lifted him a little higher, loosening the weight he carried. The country might be divided, but ordinary Americans wanted to believe unity was still possible. Washington felt responsible for honouring that hope.

When Congress later proposed a national day of thanksgiving and prayer, he saw its potential immediately. This was not the old harvest feast or the symbolic gestures shared between settlers and Native communities in the seventeenth century. This was an invitation for a young republic to pause together, look inward, and acknowledge shared fortunes in a time of unease.

Critics objected, of course. They saw federal overreach, religious interference, political theatre. Yet Washington pressed on because he recognised something his opponents did not. Nations are not held together by constitutions alone. They need ritual. They need rhythm. They need moments when people step out of their own disputes and remember the common ground beneath their feet.

The Thanksgiving That Fell Quiet Yet Still Endured

And now we come to the day itself, 26 November 1789. Washington dressed in black velvet, travelling through rain towards St Paul’s Chapel. He expected to stand among crowds, sharing this first national moment. Instead, he found a nearly empty church. The poor weather kept people indoors. Few braved the elements to attend.

It must have stung, especially after the warm welcomes of his inauguration journey. Washington had hoped Thanksgiving might become an annual tradition, a way of stitching together a country still learning how to exist. The empty pews changed his mind. He would not pursue another national Thanksgiving during his presidency.

Yet this quiet day did not fade into obscurity. Its meaning lingered, waiting for someone to pick it up again. Seventy-four years later, President Lincoln did precisely that. The United States was fractured once more, this time by civil war. After the bloodshed of Gettysburg, Lincoln used the idea of a national day of gratitude as a way to call the country back to itself. His proclamation in 1863 fixed Thanksgiving in the national calendar and ensured it would endure.

In that sense, Washington’s attempt was less a failure and more a seed. It waited through storms and generations until the ground was ready.

Why This Moment Still Speaks To Us Today

What strikes me most about this first Thanksgiving is the human simplicity beneath the political manoeuvring. Washington did not try to lecture the country. He did not scold or cajole. He reached for something humble, something ancient: the act of pausing, giving thanks, and remembering shared purpose.

This was a man who knew what division looked like. He had seen Americans point muskets at one another long before the Union ever faced the Confederacy. He had watched debate turn to anger in the halls of government. He had felt the quiet terror of responsibility when the nation seemed ready to crack.

His answer was not force or fiery rhetoric. It was a call to gratitude, offered softly, in hope rather than certainty.

That is why I see Washington’s Thanksgiving as one of the most revealing episodes of his presidency. Not because it succeeded, but because it showed his instinct when confronted with national fragility. He tried to draw people together, not by celebrating victory, but by acknowledging shared blessings in an unsteady time.

In our own era, when politics often feels like a contest of noise rather than ideas, this early attempt at unity offers something valuable. Gratitude slows us. It clears the fog. It reminds us to look beyond our chosen tribes. Washington understood that. Lincoln understood it too. Both reached for gratitude when the nation seemed unsure of itself.

On this day in 1789, the pews may have been empty, the weather miserable, the moment small. Yet the intention behind it, the desire to steady a fractured republic, still deserves attention.

Thanksgiving was born quietly, but it was born with purpose.