On This Day 1709: When a Scottish Sailor Stepped Out of Myth and Back Into the World

How Alexander Selkirk’s rescue turned lived endurance into lasting legend

On this day in 1709, a solitary figure emerged from the undergrowth of a Pacific island and walked back into human company. He was gaunt, bearded, dressed in animal skins and speaking English with a Scots accent sharpened by four years of silence. His name was Alexander Selkirk, and his rescue would echo far beyond the moment, shaping one of the most enduring stories ever written.

I have lived most of my life within a short drive of Lower Largo, the small Fife village where Selkirk was born. There is a hotel there bearing the Crusoe name, and more than once I have sat over a Sunday roast thinking about how an argument on a ship, a rash tongue, and a stubborn sense of right and wrong sent a local man to the far edge of the world. That closeness makes the story harder to shrug off. Selkirk was not a symbol or a literary device when he was left behind. He was flesh and nerve and temper, and that matters.

A quarrel that changed everything

Selkirk did not drift into legend through misadventure alone. His ordeal began with a confrontation. He was sailing as master aboard an English privateer, a ship licensed to prey on enemy vessels. The captain was young, proud, and dismissive of caution. Selkirk, older and more experienced, believed the ship was unfit for open sea. Repairs were being rushed. Maintenance ignored. The stakes were obvious to anyone who understood timber and tide.

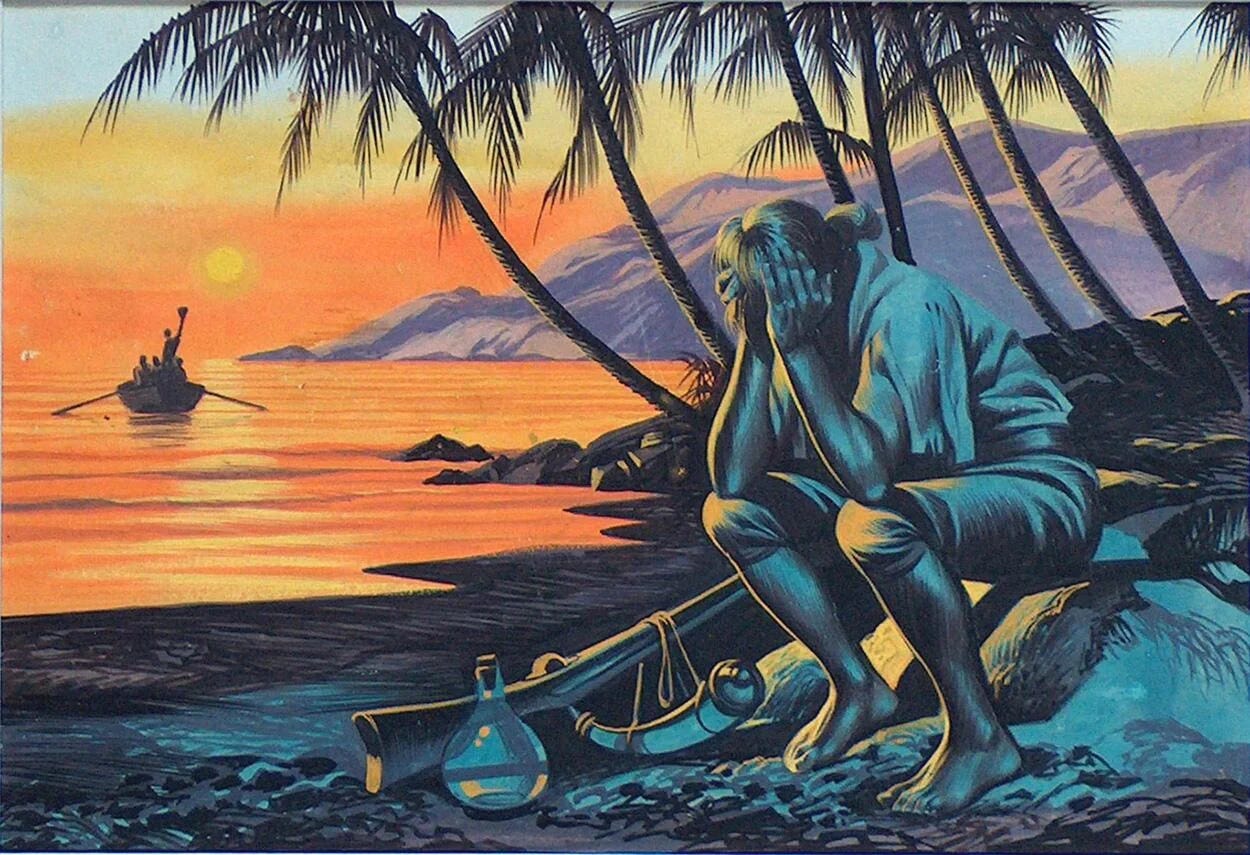

Words were exchanged. Selkirk, furious and convinced he was right, declared he would rather be put ashore than sail on what he saw as a floating coffin. It was a statement born of principle, pride, and exhaustion. The captain called his bluff. Within hours, Selkirk was standing on an uninhabited island with a handful of tools, a musket, a Bible, and the sound of departing oars cutting him off from everything he knew.

It is tempting to dress that moment up as heroic defiance. It was not. It was impulsive, human, and immediately regretted. Selkirk shouted apologies from the surf. The ship sailed on regardless. That detail matters too. History often flattens people into archetypes, but Selkirk’s mistake was recognisably ours.

Survival without romance

The island did not greet Selkirk kindly. His first shelter was crude, his food uncertain, his nights unsettled by animals and weather. He learned quickly or he would die. Fresh water came from streams inland. Food came from shellfish, turtles, wild goats, and whatever fruit he could gather. Rats plagued him until he tamed feral cats to keep them at bay.

Days were shaped by routine. Fires to tend. Traps to check. Wood to gather. He sang psalms aloud to keep his voice alive. He read and reread his Bible, not for comfort alone but for structure, a way of ordering thought when there was no one left to speak to. The sea was watched daily from high ground, a habit that bordered on obsession.

There was fear too. At one point, ships appeared that flew the wrong flag. Selkirk hid in trees while armed men searched below him, so close that he could hear them breathe. Discovery would have meant imprisonment or death. When the danger passed, the island closed around him again.

This was not a tidy tale of self improvement. It was endurance, plain and wearing. Selkirk survived because he adapted, because he worked, and because he refused to surrender the idea that the horizon might one day change.

Rescue on February 2nd, 1709

When rescue finally came on this day in 1709, it did not arrive with trumpets. Two English ships anchored offshore to resupply. Selkirk approached cautiously, revealing himself only when he heard familiar speech. The sailors who met him were stunned, not by his appearance alone but by the fact that he still spoke their language clearly after years without conversation.

His story was believed because fate intervened once more. One of the crew knew of the ship that had abandoned him and confirmed its sorry end. The vessel Selkirk had warned was unsafe had later sunk, its crew lost or captured. In that quiet validation lay a grim justice.

Selkirk returned to the sea as second mate and eventually made his way home. His survival became known in taverns and print, passed from mouth to mouth with the usual embellishments. A writer took notice and reshaped the bones of the story into something else entirely.

From lived ordeal to literary myth

The book that followed, Robinson Crusoe, borrowed Selkirk’s isolation but not his temperament or circumstances. Fiction replaced argument with shipwreck, solitude with companionship, and spiritual struggle with narrative clarity. It was a brilliant transformation, but it also softened the harsher truths.

Selkirk did not wash ashore innocent and alone. He was placed there by human decision, including his own. He did not conquer the island. He endured it. That difference matters because it keeps the story anchored to reality rather than moral fable.

When I walk through Lower Largo, it is Selkirk I think of, not Crusoe. The man who argued himself into exile and survived through stubborn labour feels closer, more instructive. He reminds us that history is rarely tidy, and that courage often looks like persistence rather than triumph.

Why this story still matters

On this day stories tend to flatten into anniversaries, neat and commemorative. Selkirk resists that treatment. His rescue on February 2nd, 1709, marks not the end of suffering but the return of a difficult man to a difficult world. He would never quite settle, and he would die at sea years later, far from home once again.

Yet his legacy endures because it sits at the uneasy junction of fact and imagination. It asks uncomfortable questions about authority, pride, survival, and the cost of being right. It also reminds us that behind every great myth there is often a human voice, raised once in anger, then carried for years in silence.

Living so close to where Selkirk began, it is impossible not to feel that pull. The story belongs to the Pacific, to literature, and to the world, but it also belongs to a stretch of Fife coastline and to anyone who has ever said one sentence too many and spent years living with it.

On this day, it is worth remembering the man as he was, not as he became in print. A sailor. A survivor. A Scot who stepped out of isolation and back into history.