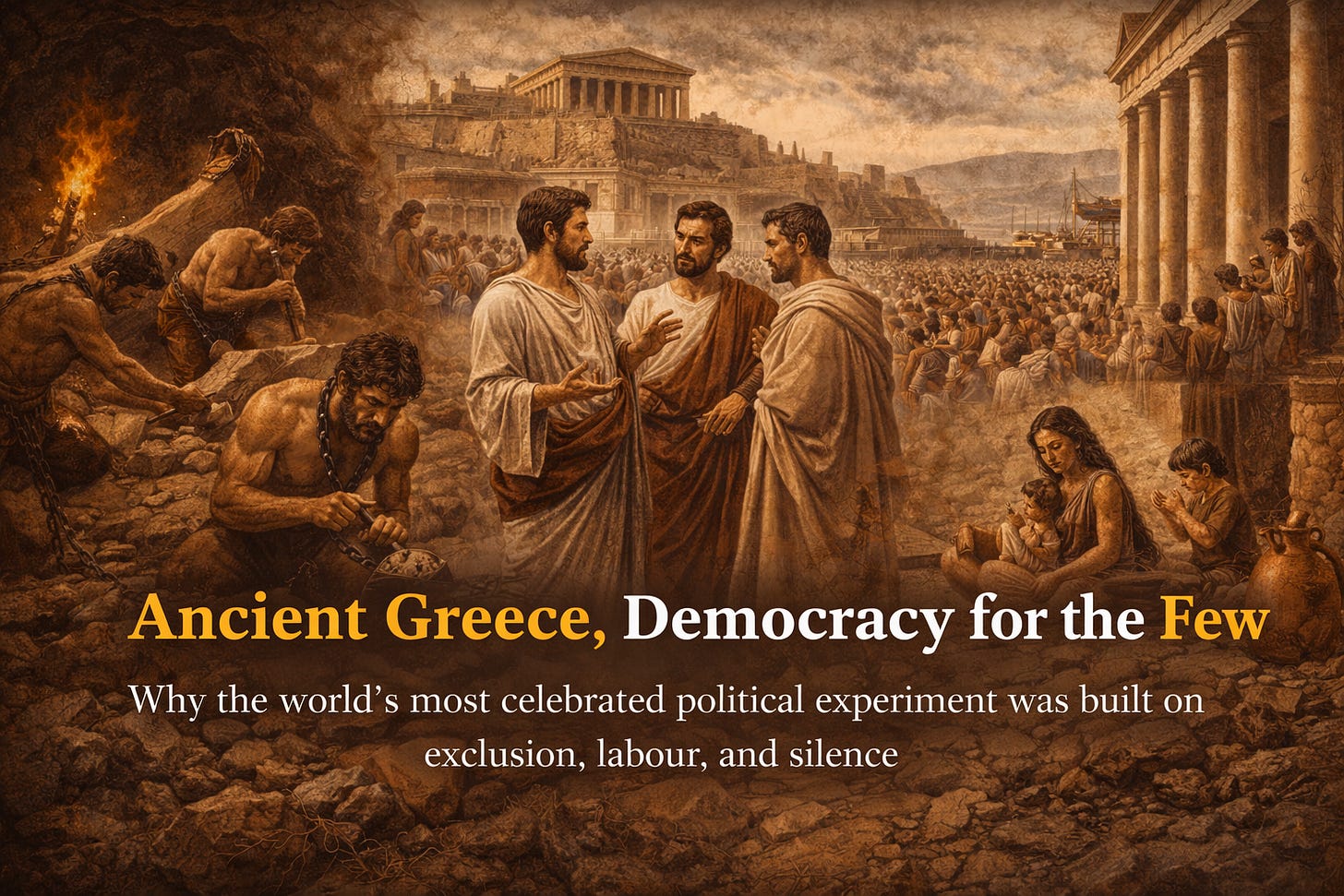

Ancient Greece, Democracy for the Few

Why the world’s most celebrated political experiment was built on exclusion, labour, and silence

Modern democracy often treats ancient Athens like a founding parent whose faults we politely ignore at family gatherings. We borrow the language, quote the ideals, and invoke the birthplace whenever democracy feels under threat. It is a bit like praising a smartphone by talking only about its sleek design while forgetting the factory floor, the supply chains, and the people whose hands never touch the final product.

Ancient Greece did not invent democracy for everyone. It invented democracy for some, and built it on the work, obedience, and exclusion of many others. This is not a moral gotcha from the present, but a historical reality that gets softened every time we tell the story too neatly.

Who democracy was actually for

When people speak about Athenian democracy, they usually mean the participation of citizens in political life. This sounds impressively inclusive until we ask who counted as a citizen. The answer immediately narrows the picture.

Adult male citizens born to citizen parents could vote, speak in the assembly, and hold office. Women could not. Enslaved people could not. Foreign residents who lived and worked in Athens, often for generations, could not. Children could not. The majority of the population was excluded from political life by design, not accident.

Estimates vary, but at most around 10 to 15% of the people living in Athens enjoyed political rights. Democracy was real within that group, but it rested on the assumption that everyone else would stay silent.

The word democracy comes from demos and kratos, people and power. The uncomfortable truth is that the people were carefully defined.

Leisure made possible by labour

Active political participation takes time. Assembly meetings could last all day. Jury service required hours of listening, debating, and deciding. Holding office demanded attention and availability.

This leisure did not appear from nowhere. It was made possible by enslaved labour and domestic work largely carried out by women. While citizen men debated laws, others cooked, cleaned, farmed, fetched water, raised children, and kept the city functioning.

Enslaved people worked in homes, workshops, fields, and mines. The silver mines at Laurion were particularly brutal, fuelling the Athenian economy and its naval power through back breaking labour in deadly conditions. Without that silver, there is no fleet. Without the fleet, there is no empire. Without empire, there is no confidence in democratic Athens as a dominant power.

Democracy, in other words, depended on coercion elsewhere. The freedom of some was secured by the unfreedom of others.

Women at the centre, kept at the edges

Women were essential to Athenian society and systematically excluded from its political life. They managed households, supervised enslaved workers, raised future citizens, and performed vital religious roles. Yet they had no vote, no legal independence, and little public voice.

This exclusion was not incidental. It was argued for, defended, and embedded in law and custom. The ideal citizen was imagined as male, rational, and free from domestic obligation. That freedom was only possible because someone else handled those obligations.

It is tempting to see this as an unfortunate blind spot of the time. In reality, it was a structural choice. Democracy was built around a narrow image of who deserved to participate.

Empire behind the ideals

Athens liked to present itself as a beacon of freedom, especially when contrasting itself with rivals. Yet its wealth and confidence were tied to imperial control over other Greek city states.

Tribute flowed into Athens from allies who had little choice in the matter. Money funded public buildings, festivals, and payments for political participation. Citizens were paid to attend the assembly and serve on juries, a progressive move that allowed poorer citizens to take part.

That payment, however, came from imperial extraction. The democracy of Athens was subsidised by the lack of democracy elsewhere. When allies resisted, Athens responded with force.

This contradiction did not go unnoticed at the time. Critics questioned whether freedom at home could coexist with domination abroad. The tension between democratic ideals and imperial behaviour was not a modern reinterpretation. It was a live issue in the ancient world.

Speech, persuasion, and power

One of the great achievements of Athenian democracy was the centrality of speech. Persuasion mattered. Arguments were heard, challenged, and voted on. Rhetoric became a skill, even an art.

Yet this emphasis on speech also privileged those trained to speak well. Education was not evenly distributed. Confidence, upbringing, and wealth shaped who could hold a crowd. Formal equality in theory did not guarantee equal influence in practice.

Demagogues exploited fear. Elites steered debate. Popular decisions sometimes led to catastrophic outcomes, including mass executions and disastrous military campaigns.

Democracy did not always produce wise decisions. It produced decisions made by those allowed to speak, shaped by emotion, persuasion, and power.

Why the myth survives

So why do we still talk about ancient Greece as the pure origin of democratic virtue? Partly because the story is useful. It offers a lineage, a sense of inheritance, and a reassuring narrative that democracy is ancient, natural, and destined.

It also allows us to sidestep harder questions. If democracy was flawed from the beginning, then it has always required struggle, expansion, and correction. It was never complete. That is less comforting than the idea of a golden birth moment followed by decline and recovery.

The myth persists because it flatters modern democracies. It suggests we are heirs to wisdom rather than participants in an ongoing experiment.

What the blind spot reveals about us

The danger is not in admiring ancient Greece. The danger is in sanitising it. When we strip away exclusion, coercion, and inequality, we learn the wrong lessons.

Democracy does not appear fully formed. It emerges within specific conditions, shaped by power, economics, and social boundaries. It expands because people push against those boundaries, not because the system naturally corrects itself.

Ancient Greek democracy matters precisely because it was limited. It shows how radical ideas can coexist with deep injustice. It reminds us that participation must be fought for, defended, and widened.

Ending where we began

There is a modern analogy worth sitting with. Praising Athenian democracy without its context is like celebrating a gleaming city skyline without asking who cleaned the offices, laid the cables, or lived in the shadows beneath it.

Ancient Greece gave us the language of democracy, but not its finished form. That work has never been finished. The real lesson is not that democracy was born perfect, but that it has always been partial, contested, and dependent on who is allowed in the room.

History’s blind spot is not that ancient Greece failed to live up to modern standards. It is that we keep pretending it ever tried to.

Very insightful essay. Context is so important to understanding such concepts